New York City Council

Inside the quiet race for New York City's second-most powerful position

The New York City Council speakership goes to whomever can convince around 125 political power brokers, all with opposing interests, that they'll have an ally in City Hall.

The very simple City Council speaker machine. Kathleen Fu

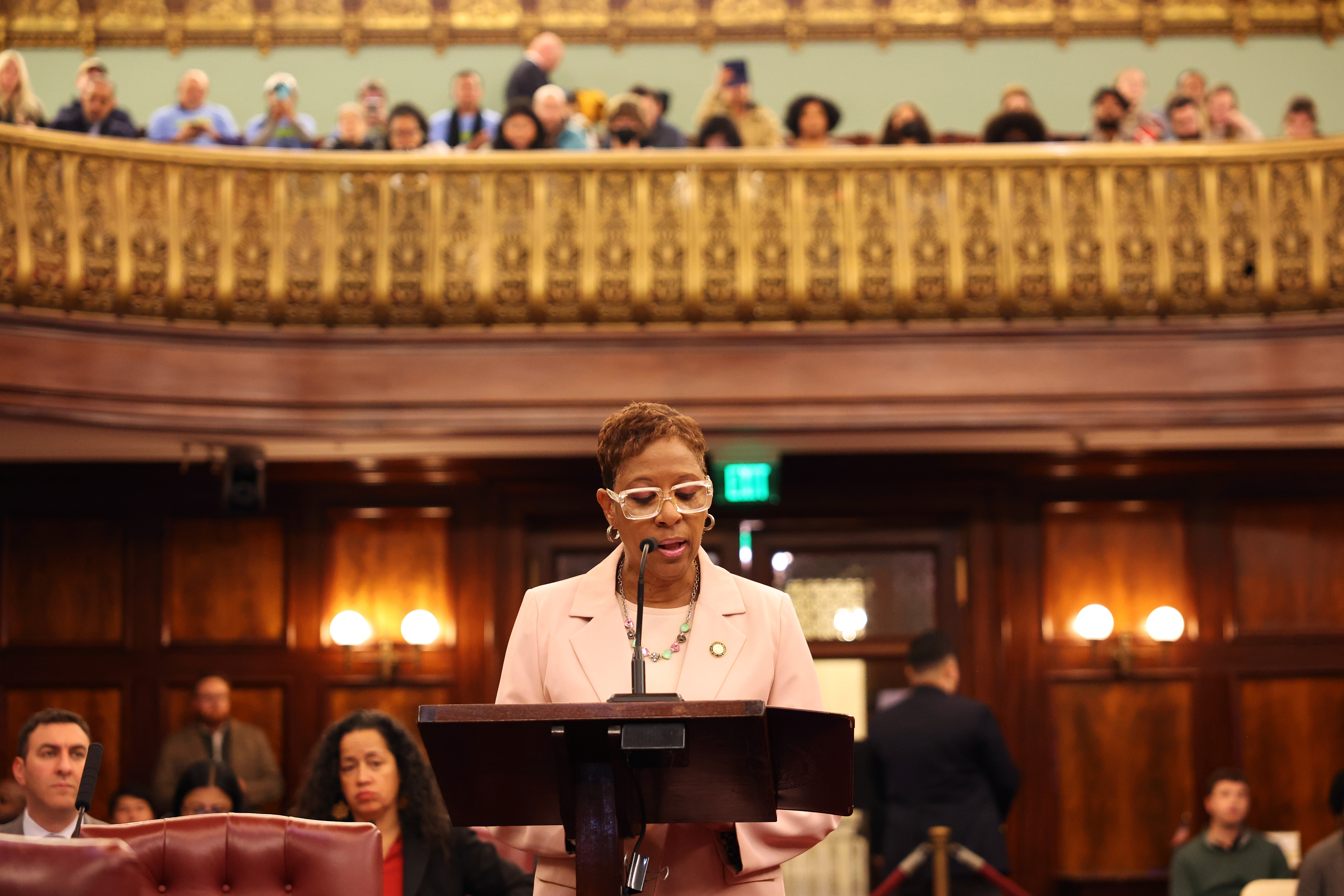

The second-most powerful person in New York City politics is not elevated to the role by the voters of New York City. The speaker of the New York City Council, currently Adrienne Adams, has the authority to set the council’s agenda, which means she has unmatched influence on what becomes New York City law. With a little maneuvering, she can convene a commission to change the city charter, subpoena members of the mayor’s administration and override mayoral vetoes. She can schedule the council’s meetings, hire its central staff, choose its committee chairs, dispense its discretionary funding and negotiate the city’s budget on its behalf. She chooses who sits on the Land Use Committee, which gives her power over what gets built in New York City – and what doesn’t.

The speaker’s annual salary is currently $164,500, $16,000 more than her colleagues. The speaker has a huge, well-paid staff and a big City Hall office, for which art can be borrowed from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in addition to a spacious suite at 250 Broadway – both with private bathrooms. She is ferried around the city in a black SUV accompanied by a full-time police detail. She holds immense sway over the members of the council, setting their operating budgets and determining which committees they sit on. She decides which members are part of the council’s leadership and who is on the team that negotiates the city’s budget. She can decide which offices go to which members and choose where members sit in the chamber.

As the city stumbles through the most unpredictable mayoral election in recent history, a much more subtle race is underway to succeed her. In some ways, the race is simple. There are 51 members in the body. You need 26 votes to win. As the City Charter puts it: “The council shall elect from among its members a speaker and such other officers as it deems appropriate.” But to understand the race for council speaker is to understand the lumbering, transactional, redundant, at times corrupt and at times beautiful system through which power flows in New York City. Every speaker race is unique. Campaign finance laws and term limits have shifted. The date of the primary election has moved, and the influence of county machines has waned. There is no surefire way to win, yet it’s a process that candidates approach with relentless strategy. “It was a very intense 2 1/2-year period where I worked my butt and my brains off by being in every corner of the city,” said Corey Johnson, who was elected speaker in 2018.

This “deal,” as some participants call the speaker selection process, is a yearslong conversation that involves political influencers across the city, and it plucks the strings that connect them to one another. But the outcome – hashed out at a beachfront hotel in San Juan, Puerto Rico – can almost be a fluke. Everyone and no one decides.

Getting the members on your side

Since the New York City Charter was changed in 1989 to establish the position, there have been six City Council speakers. People who have been involved in a speaker race often say that it is wholly different from a typical election. It’s more of a popularity contest. “It’s an enormous emotional lift because it’s a race that’s a bit like running for class president. There’s no polls. It’s just sort of all rumor and gossip and personal relationships,” said Gifford Miller, who was elected speaker in 2002. “It’s not like when you’re running for mayor, you go out and you do ads and you take polls. … Everything is much more uncertain when you’re running for speaker.”

Miller, running as a 31-year-old Manhattan upstart, won the first speaker’s race after the council adopted term limits, and the majority of his colleagues were entering the council for the first time. He modeled his campaign after Republican Rep. Newt Gingrich’s 1994 “Contract with America” strategy to win back the House. Rather than allow the county parties in the Bronx, Queens – and to a lesser extent, Brooklyn – to decide who the new speaker would be on their own, Miller visited every district to build relationships with his future colleagues. He knocked doors with his chosen candidates, gave them advice and created a political action committee called Council 2001 to fundraise for them. “I went out and endorsed in 36 of the 51 districts, and I went and campaigned with people for a year and a half every day,” Miller said.

His approach has been replicated by several of his would-be successors and continues to influence the way the race is run, though the election schedule and campaign finance laws have changed. One indicator that Manhattan City Council Member Julie Menin is mounting a serious campaign for speaker in 2026 is her campaign fundraising. Her committee, Julie Menin 2025, has made maximum $1,050 donations to 16 of her colleagues in the council so far and to one candidate in an open seat: teachers union operative Dermot Smyth. Menin has also been helping her allies get on the ballot. “I am really focused on helping my colleagues with their reelections, and that needs to be the focus right now,” Menin said.

Due to the quirks of term limits, the amount of turnover in the council isn’t consistent. As was the case during Miller’s race, sometimes, the majority of the body is entering for the first time. This was also the case in 2021, when Adams became speaker, leading a body that included nearly three-dozen new members. In other cycles, the majority of the council is returning – like when Johnson was running in 2017 or this year. In both scenarios, candidates for speaker are simultaneously trying to firm up relationships with their returning colleagues while also backing the right candidates in open seats.

Meddling in competitive open seats is always a gamble. As a speaker hopeful is simultaneously trying to curry favor with labor or county machines, they may choose to back the same candidate as those interests. Sometimes, a speaker hopeful will find a way to appear to support multiple candidates in the same council primary, if not directly donating to each candidate, then by asking surrogates to donate to or advise multiple candidates on their behalf.

For new members, speaker race politics can feel daunting as they consider who to vote for: “You just got elected, you’re not an expert at doing your job, and all these voices are coming at you,” said Queens Council Member Sandra Ung, who was first elected in 2021. “So are all the other players in the background, and you haven’t even taken office yet.”

“People move in herds”

While each individual member of the City Council casts a vote for speaker, many of them don’t decide who to vote for independently. Members may be part of a voting bloc led by outside interests. “The reality of politics is that people move in herds,” said Jason Ortiz, former political director at the Hotel and Gaming Trades Council and one of the strategists of Johnson’s race. Again, each speaker race is different, but there is broad consensus on the main forces involved.

“There’s probably a cast of, I don’t know, 125 people in the city that you kind of have to touch and create relationships with over the course of a speaker’s race campaign: county leaders, of course council members, labor unions,” Johnson said. “It’s a lot of folks.”

Historically, the Bronx and Queens Democratic Party chairs have each controlled blocs of votes. They have essentially haggled over who to make speaker, compromising by choosing a Manhattan candidate over whom they shared influence. In her inaugural address as speaker in 2006, Christine Quinn, who declined to be interviewed for this story, name-checked then-Bronx boss Jose Rivera, Queens boss Thomas Manton and Brooklyn boss Vito Lopez in her second sentence after “Good afternoon.” In exchange for their support, county machines have sought well-paid central staff jobs for party insiders, leadership roles and powerful committee chairs within the council for county members, and spending on community-based organizations connected to the county apparatus.

In 2013, Melissa Mark-Viverito famously subverted Bronx and Queens by forming a coalition with labor, progressives and the Brooklyn Democratic Party machine. “Typically, Bronx and Queens have considered themselves to be the kingmakers,” she said. “In my race, they didn’t play a role. They were not the decision-makers. And I’m sure they didn’t appreciate that.”

In the ongoing speaker race, which will culminate with a vote at the council’s first meeting of 2026, City Council Majority Leader Amanda Farías said she’s already begun the conversation with the Bronx Democratic Party, led by state Sen. Jamaal Bailey. “First and foremost, I went to my county members and I went to my county leader before any outward motivations to members or conversations, because that is home base,” she said. “My county is supportive of me running for speaker.” An illustration of the fluidity of the race – a source close to the Bronx Democrats was careful to note that that doesn’t yet amount to an endorsement.

County apparatuses are deeply entangled with labor leaders, primarily from the “big three.” The building service workers union 32BJ SEIU, the hotel workers union Hotel and Gaming Trades Council and public employees union District Council 37 have huge sway. The big three are not always united behind one candidate. They were split in 2021 and in 2017. “Unions are always going to be relevant because they do have membership in a constituency that is important,” Mark-Viverito said. Health care workers union 1199SEIU was a key factor in her victory. The hotel trades were essential for Johnson. “The way that organized labor can be helpful is the way that county organizations can be helpful,” Ortiz said. “Organized labor will play an outsized role in electing the members. Though it isn’t something that we (HTC) were explicit about in 2021, it was implicit that we are going to help you in your particular race, and in the spirit of that partnership, we’re going to be involved in helping you decide who the next speaker is.”

Another sign Menin has her eye on the speaker role is her lead sponsorship of two high-profile labor bills: her hospital price transparency bill was important to 32BJ SEIU, and her Safe Hotels Act was a major priority for the Hotel and Gaming Trades Council.

The mayor or mayor-elect is always a consideration, but rarely a deciding factor. Bill de Blasio reportedly brokered a deal to peel the Brooklyn Democratic Party votes away from then-Council Member Dan Garodnick, helping clinch the speakership for Mark-Viverito. Though she gets annoyed when the ex-mayor gets credit. “There continues to be this want to minimize my role as speaker and my victory as speaker by saying that the mayor controlled this process,” she said. After all, Mark-Viverito was one of de Blasio’s first backers in the mayoral race. “It’s fascinating, right, as a woman of color in particular, that there's always this attempt to say that I had nothing to do with it, that somehow it was the results of the work of somebody else, a man, at that.” In 2021, then-Mayor-elect Eric Adams’ behind-the-scenes backing of Francisco Moya might have actually harmed Moya’s bid, as it motivated progressives to work against him.

Speaking of progressives, caucuses within the City Council, though not as durable as county machines, have organized to vote together. Progressives partnered with labor, the mayor and the Working Families Party to elevate Mark-Viverito, while the Republicans as a bloc supported Johnson in 2017. Several individual members of Congress can also get involved. The influence of former Reps. Joe Crowley, Charlie Rangel and Rep. Jerry Nadler has given way to Reps. Hakeem Jeffries, Adriano Espaillat and of course Queens boss Rep. Greg Meeks.

And the candidate’s identity relative to the other city leaders can come into play. For example, as New York City elected its first woman-majority council in 2021, with a male mayor-elect, comptroller-elect and public advocate, there was increased interest in choosing a woman speaker. But identity isn’t always determinative. There was also interest in electing a Latino speaker due to the absence of Latino leaders in the highest ranks of city government. And when Latino front-runner Moya’s bid failed, Carlina Rivera and Diana Ayala, two other Latina contenders, were not elevated in his place.

The cosmic aspect

All these forces – incoming members, returning members, labor unions, county machines – influence one another and are also influenced by lobbyists, state lawmakers, press and advocacy groups. (The process also doesn’t end when the speaker is elected. These players continue to shape the workings of the council and the choices of the speaker throughout their term.) One operative familiar with the process described the art of running for speaker as creating an “echo chamber” around a candidate. You start years in advance with the members who are already your allies, gently floating the idea. Once you have tacit commitments from them, you take that and parlay it to outside influencers. Then you take those conversations and relay them back to the members to see if you can get them to firm up their support. It’s a spiraling process that builds on itself.

And it can all fall apart in an instant. Sometimes you do all of it. You work hard for two years, you fundraise and knock doors and carry petitions for all the right people. You make dozens of daily calls. You carry the right bills, have coffees and drinks and fundraisers with all the right people. You go to all the advocacy group forums. And you still lose.

And sometimes you do very little of this, and you still end up speaker.

Speaker Adams, who also wasn’t made available for this story, was not considered to be a leading speaker candidate in 2021. Other candidates were fundraising and campaigning with members for months and years while her campaign involvement was minimal.

By the time New York’s political class had flown to San Juan, Puerto Rico, for the annual Somos conference, it was not at all clear who would clinch it. Adams emerged as the compromise candidate at the last minute, surpassing Justin Brannan, Keith Powers, Ayala and Rivera, who were each, at one point or another, seen as front-runners, and Moya, who had the backing of the mayor-elect.

Now that Speaker Adams is term-limited and running for mayor, Farías, Menin and Brooklyn Council Member Crystal Hudson are the three names that come up most often to succeed her. But in the speaker’s race, there is no petitioning, no deadline by which you need to declare yourself a candidate. The next speaker may not have even told anyone they are running yet.

“So much of the race is circumstance and luck,” Ortiz said. “Human beings don’t like to acknowledge luck.”