The number of students who experienced homelessness in New York City last school year could fill Yankee Stadium nearly three times over. That’s according to a new report released Monday from Advocates for Children of New York, which found over 146,000 public school children – or 1 in every 8 – didn’t have a permanent place to call home during the 2022-2023 school year.

While that staggering figure is a record high, driven in part by the recent surge of asylum-seeking families arriving in New York City, homelessness has long been a major issue in the nation’s largest school system. Last academic year was the ninth consecutive year in which more than 100,000 public school children experienced homelessness.

Of the over 146,000 students impacted last year, 41% spent time living in city shelters, 54% were doubled up with other families, and 5% were unsheltered or living in cars or hotels, according to the nonprofit’s annual report on New York State Education Department records. That’s a 23% increase from the 2022-2023 school year, spurred in large part by an uptick of students living in shelters.

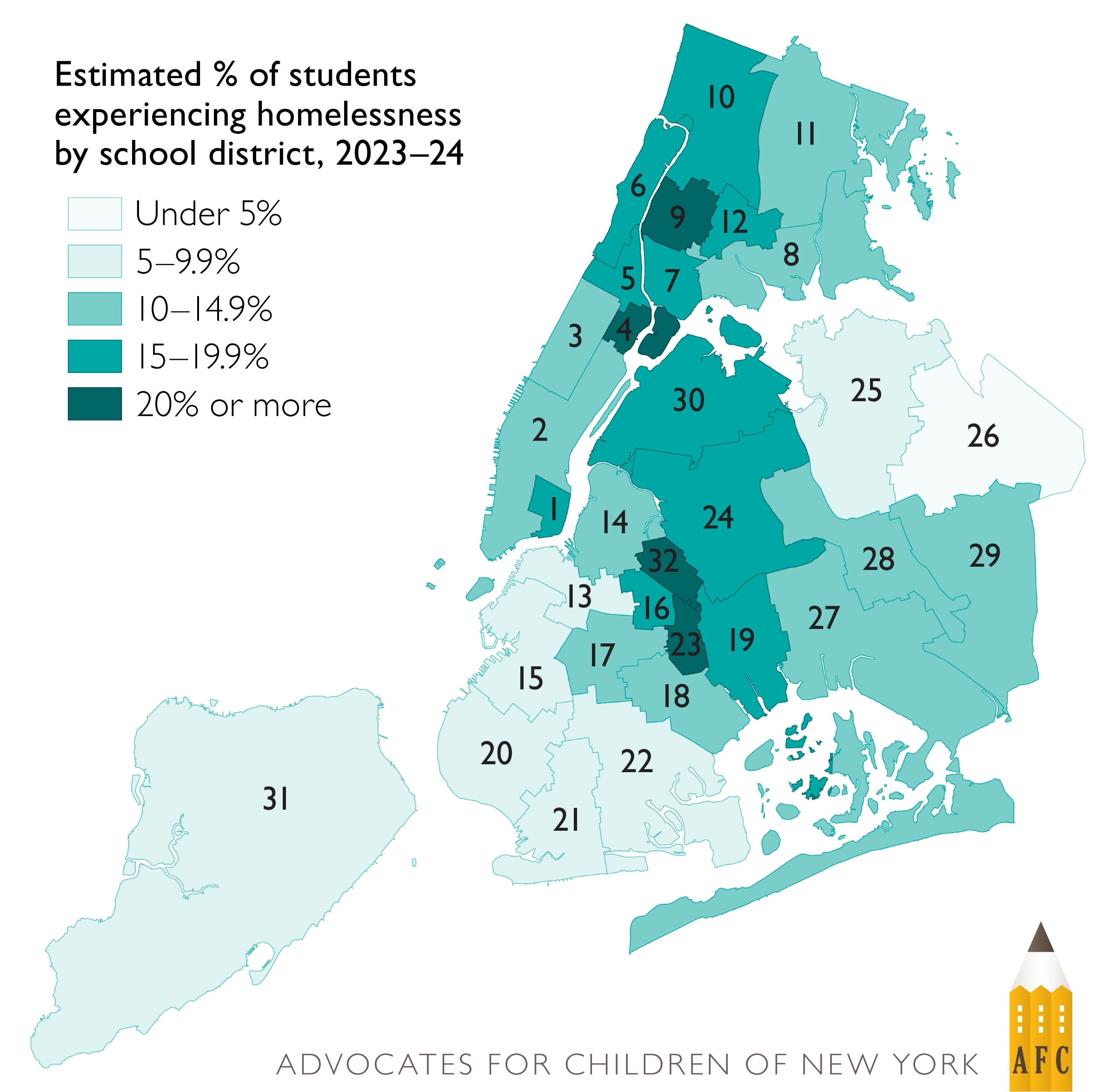

While these children are located all around the city, students who experienced homelessness last year lived in higher numbers in upper Manhattan, Brooklyn’s Brownsville and Bushwick neighborhoods, and the southwest Bronx. In both Manhattan and the Bronx, nearly one in every six students were impacted. It’s important to note too that with just over 912,000 students, enrollment was still down last school year compared to pre-pandemic numbers, making the 146,000 figure all the more striking.

A spokesperson for the New York City Department of Education said that one of the system’s priorities is to provide students experiencing homelessness with the support and resources they need to succeed in school.

“We have long established many critical supports to help students and families in temporary housing including field support, enrollment support, transportation services for students and parents, access to counseling, immunization assistance, and academic support,” the spokesperson said in a statement.

While all students who experience homelessness and housing insecurity are uniquely vulnerable and face more obstacles to succeeding in school than their peers, those challenges are especially compounded for children living in shelters. During the 2022-2023 school year, about one in every 32 students in shelter were suspended from school compared to one in 49 of their permanently housed peers. Academically, a mere 26% of third through eighth grade students living in shelters received “proficient” scores on the state language art exams, and just 18% were proficient on math exams. A sweeping 67% of these students were chronically absent – a term meaning they missed at least one out of every ten school days. That’s in part because even physically getting to school can be a challenge for these students. Children are often assigned to shelters far from their current schools – sometimes under the city’s 60-day policy for migrant families and sometimes for families entering the general shelter system – meaning students must choose between embarking on lengthy daily commutes or transferring to another school.

“It is unconscionable that, year after year, tens of thousands of students in this city don’t have a

permanent home,” Jennifer Pringle, director of Advocates For Children’s Learners in Temporary Housing Project, said in a statement. “While the city works to help families find permanent housing, it must also focus more attention on helping students succeed in school. School can be the key to breaking the cycle of homelessness, but so many children, especially those in shelters, continue to fall behind.”

As the state currently reexamines its school funding system – a longstanding formula known as Foundation Aid that determines how much money is sent to school districts based on student need – Advocates for Children and a coalition of other organizations urged the state to update the formula to add funding for students in temporary housing.

NEXT STORY: New York’s MWBE programs should be safe from Trump