Transportation

Congestion pricing is indefinitely ‘on pause.’ NYC doesn’t have a backup plan to meet climate goals.

“We are certainly not waiting on congestion pricing,” Deputy Mayor Meera Joshi said, of the city’s emissions reductions efforts.

Gov. Kathy Hochul indefinitely paused congestion pricing in June, rendering tolling infrastructure at least temporarily useless. Liao Pan/China News Service/VCG via Getty Images

New York City is not yet making contingency plans for how to achieve its own key environmental goals if Gov. Kathy Hochul’s “pause” on congestion pricing remains in place.

The controversial road-tolling program, which Hochul unexpectedly halted just weeks before its planned start date in June, was set to fund a hefty chunk of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s capital plan, and some long-awaited subway modernization and accessibility projects that plan included. Much of the concern in the weeks after that surprise decision has been targeted on how the state plans to fill the $15 billion hole in the MTA’s capital budget.

But congestion pricing, as its name suggests, is also an environmental policy aimed at reducing vehicle congestion in Manhattan’s Central Business District – and reducing harmful emissions in and around the city. That aspect of the program would have been important to New York City meeting its own goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, according to a report the city released in April.

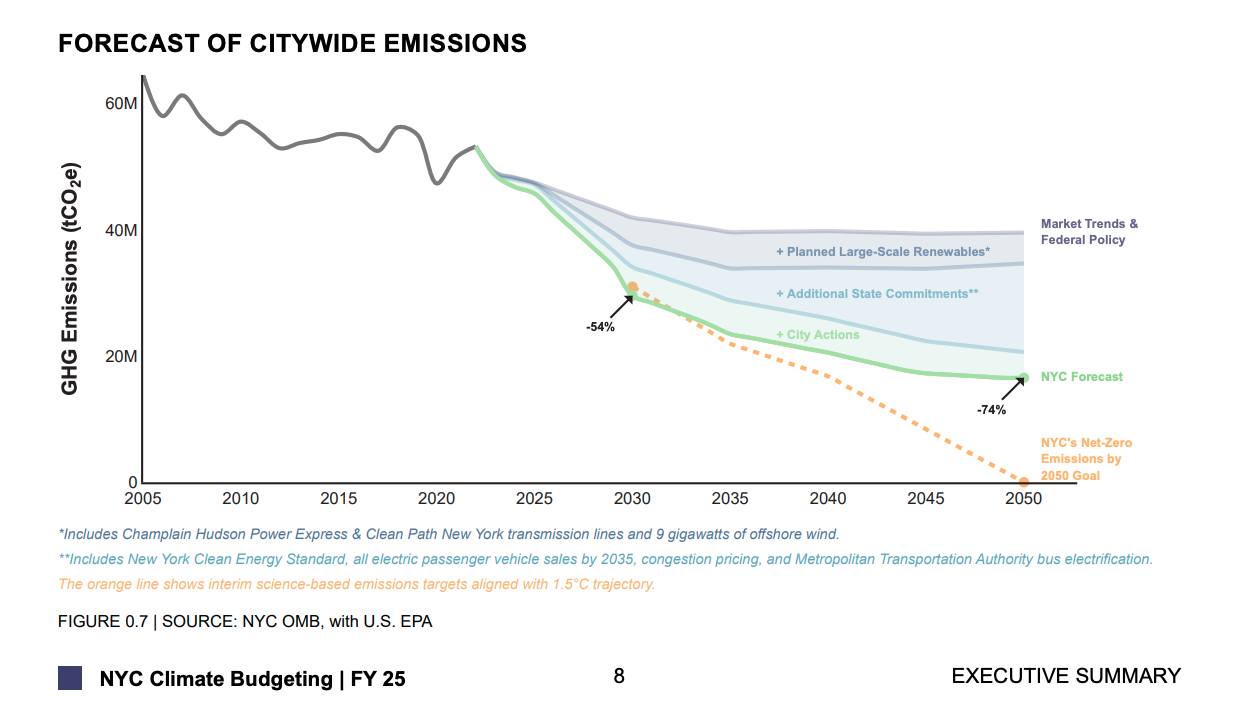

In the city’s climate budgeting document, the Office of Management and Budget reported that by implementing a range of environmental city and state policies and commitments – such as mandatory building decarbonization – the city will have the potential to reduce emissions by 74% by 2050. One of the policies identified in the report that would get the city closer to that goal was congestion pricing.

It’s not the first time that the city has recognized congestion pricing – a state program – as key to its own ambitious climate targets. The “PlaNYC: Getting Sustainability Done” report released in 2023 described it as “the most important step” to shifting vehicle trips to sustainable modes of transportation.

Asked how the city will make up for the potential loss of congestion pricing as it pursues net-zero emissions, Deputy Mayor for Operations Meera Joshi said on Tuesday that the city won’t be doing a “full final analysis” until final decisions on congestion pricing are made. “Congestion pricing is one factor. It’s on pause,” said Joshi, who also sits on the MTA board. “As we sort out what the future looks like, it will be integrated into all analysis that’s dependent on traffic and emissions.” Any updates would be reflected in the climate budgeting publication released next April, according to City Hall.

The city’s own work toward emissions-reductions, however, is proceeding, she said. “We are certainly not waiting on congestion pricing,” Joshi said. “We have several initiatives moving forward that are aggressively lowering emissions in New York City.” Among those, Joshi mentioned Local Law 97, mandating building emission reductions, as well as transportation-focused actions like electrification of for-hire vehicles and school buses.

While congestion pricing is mentioned in the city’s climate budgeting document as one of several major state commitments that was factored into the city’s forecast of emissions reduction over the next couple decades, it’s not clear exactly how great a share of the anticipated reduction congestion pricing would be responsible for. City Hall has not clarified that in response to City & State inquiries, but referred to it as one of many state commitments that impact emissions in the city.

As Mayor Eric Adams has supported Hochul in her decision to pause congestion pricing, citing a need to “get it right,” some advocates have urged the mayor and his administration to acknowledge and plan for the loss of the positive environmental outcomes associated with congestion pricing if it is not ultimately implemented.

Eddie Bautista, executive director of the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance, said that climate activists have viewed congestion pricing as essential to the city’s climate future. “Congestion pricing was always a core part of the solution,” he said.

“Even if they find the money to fund the MTA – which is a big if – without congestion pricing, you’re also losing all of these other key benefits. Reducing traffic, reducing traffic fatalities, making the zone more livable, and the climate impacts,” said Sara Lind, co-executive director of the street pedestrian advocacy group Open Plans. “I think the city is going to have to reckon with the fact that we’re losing those climate benefits.”

How much the Adams administration will reckon with that as congestion pricing remains in limbo is unclear. Adams brushed off a question last month about whether the city will have to step up to address vehicle congestion on its own if congestion pricing isn’t implemented. “We are doing an amazing job in addressing congestion, and we're going to continue to do so,” he said at a July press conference.

When previously asked about Hochul’s pause on congestion pricing, Adams has echoed her concerns about a new toll harming the city’s economic recovery. “I don't want to do anything that's going to get in the way of tourism and other economic impacts. She understands that,” he said at another press conference last month. “I have a lot of faith in the governor. We’re going to get it right. I’m sure we’ll deliver a good product.”