Energy & Environment

The Army Corps wants to protect Jamaica Bay from climate change. Environmentalists say they might ruin it in the process.

A plan to close in the bay with a sea gate to protect against future storms could cost billions of dollars and imperil natural marshes.

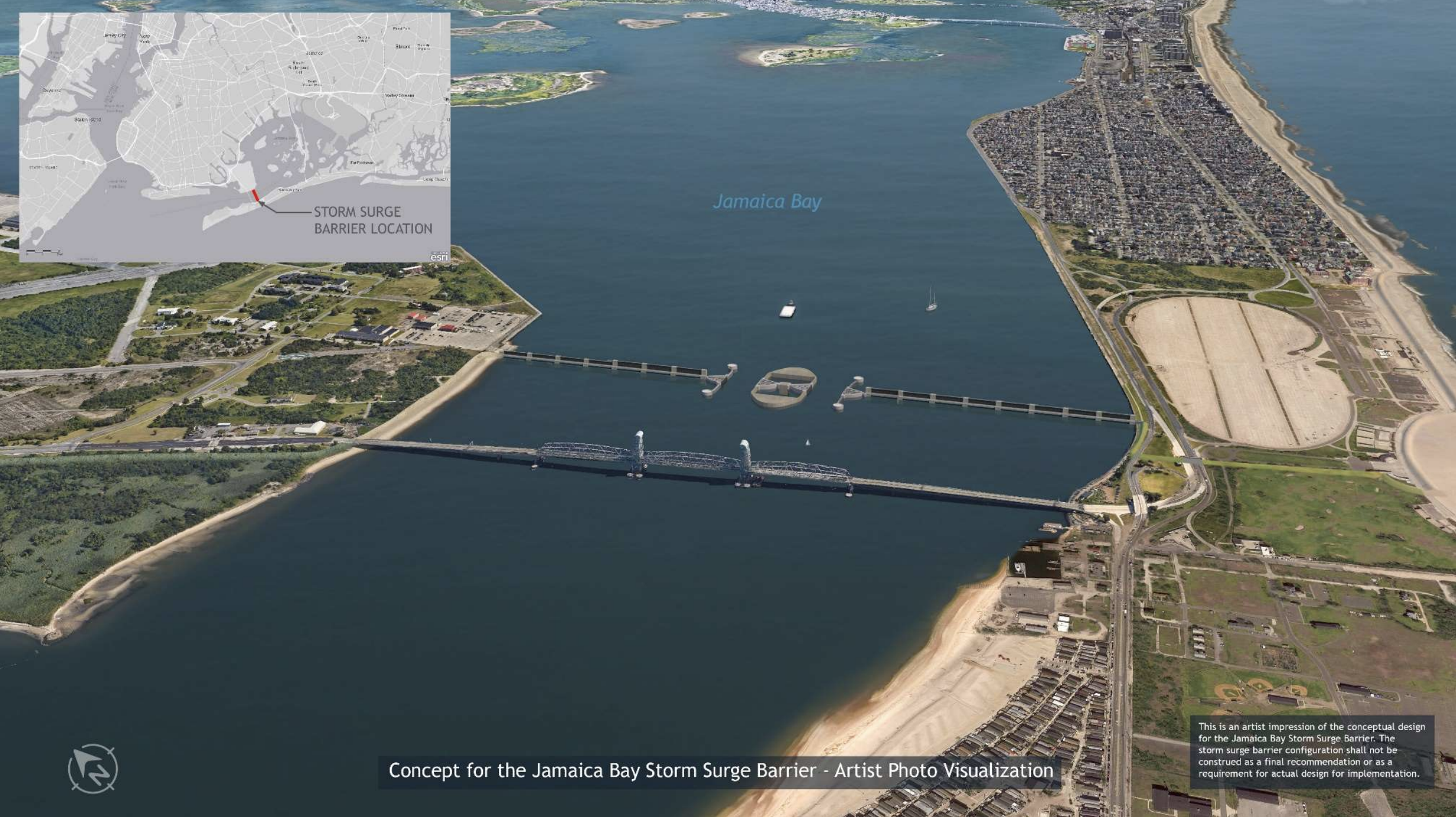

Jamaica Bay could be sealed off by the Army Corps of Engineers’ proposed storm surge barriers. Elias Guerra

An hour south of the dazzling lights of Times Square, hidden among the remaining salt marshes of Jamaica Bay, is an island called Broad Channel. A few thousand people live here, including, for almost 50 years, Barbara and Fred Toborg. They can watch as egrets come to feed in their backyard at high tide or visit the nesting ospreys in the wildlife refuge blocks away. It’s paradise much of the time, but it’s also disappearing. Over a decade ago, the Toborgs had three feet of water in their kitchen from Superstorm Sandy.

In New York City, flood days have doubled from pre-1985 levels, according to the climate change think tank Climate Central. To protect people like the Toborgs, and the millions of people living in the region surrounding Jamaica Bay, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers plans to build barriers partially enclosing Jamaica Bay and other areas vulnerable to storm surges. The Army Corps’ current proposal would integrate a collection of measures: walls along the water, elevated waterfronts and gates at the entrances of waterways, to the tune of $52 billion. In Jamaica Bay, the Army Corps proposes to build a 3,800-foot gate that would sit at the entrance of the bay, and potentially cost over $2 billion.

But the salt marshes in Jamaica Bay provide habitat for all life in the bay, and they depend on the ocean for water and sediment exchange. Scientists and activists are warning that with human-made barriers in the way, the ecosystem of Jamaica Bay would be severely disrupted. Critics say the Army Corps has not seriously considered how their plan, officially called the New York-New Jersey Harbor and Tributary Study, “Alternative 3-B,” will impact the marshes – or how protecting the marshes helps reduce flooding.

As the sea rises over the next few decades, it could swallow the Toborgs’ home and other coastal areas of the city. Although their home is at stake, they don’t agree with the Army Corps’ approach.

“It’s going to be a while before our channel is underwater,” Barbara Toborg said. “Cutting off the water over there, it’s going to come in somewhere else.”

The Army Corps of Engineers plans to start building in 2030, and they plan to finalize their study of the region this year before moving into the preconstruction and engineering phase. Then Congress will decide whether or not to fund the project, if New York and New Jersey want to proceed with the construction.

Environmental groups representing Jamaica Bay, Flushing Bay, the Bronx River and the Long Island Sound, among many others, have criticized the plan for only focusing on storm surges, instead of including all types of flooding like rainfall and high-tide flooding (also called sunny-day flooding). They say that the plan fails to address issues of sewer water trapped behind barriers during storms, and that the Jamaica Bay barrier has not been sufficiently studied.

Bernice Rosenzweig, an OSilas Endowed Professor in Environmental Studies at Sarah Lawrence College, said the Army Corps of Engineers’ analysis was too limited.

“They can only consider very tangible property damages. But that's not really a good descriptor of all of the costs,” Rosenzweig said.

The Army Corps said in an email to City & State that they are incorporating suggestions from the state Department of Environmental Conservation and others. “However, the feasibility of implementing major changes to the study’s scope, particularly in terms of funding, remains uncertain.”

The vanishing marshes

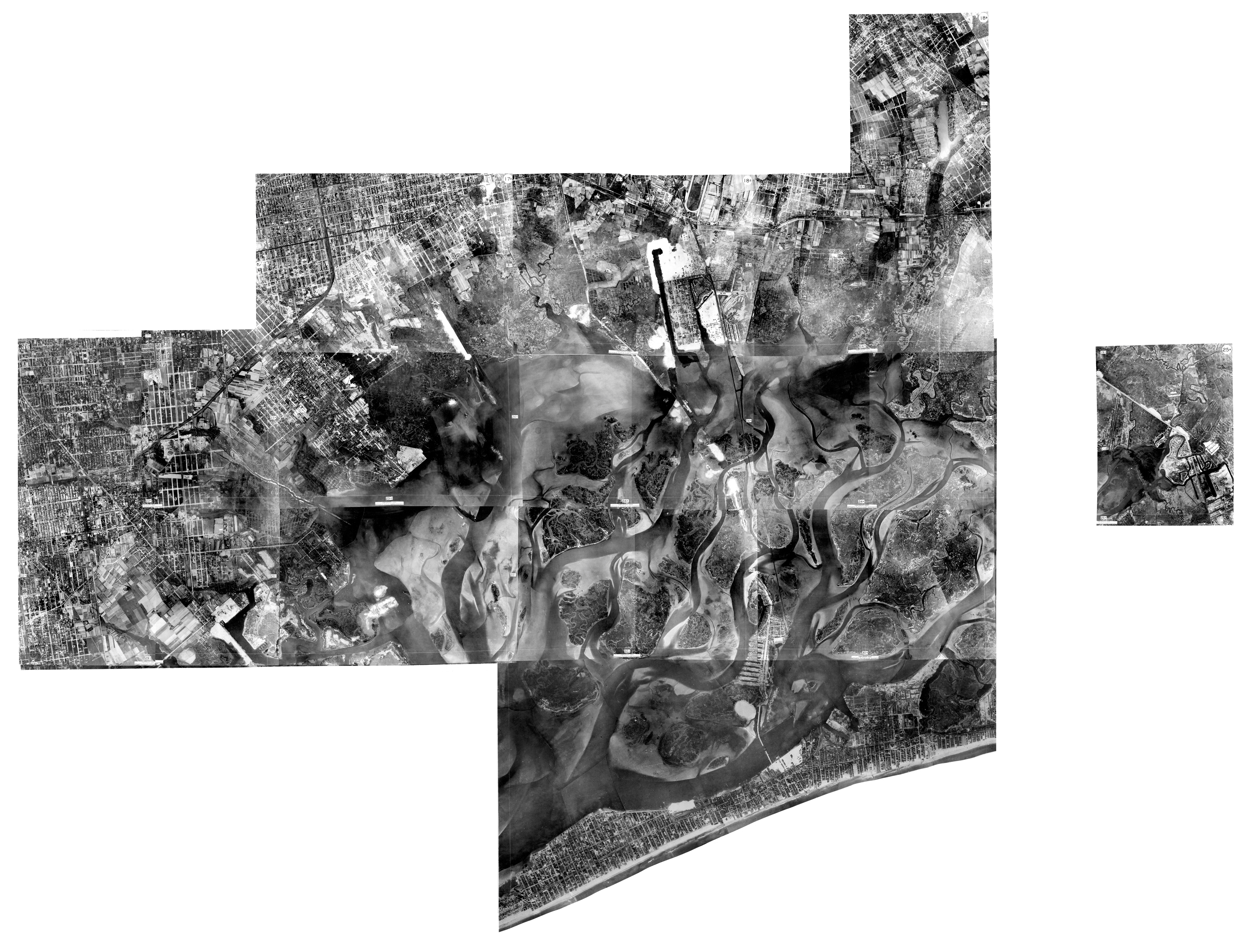

Hundreds of species of birds use the bay and the wildlife refuge for feeding and resting, some migrating across continents, along the Atlantic Flyway. Ospreys, peregrine falcons, piping plovers and the secretive barn owl can all be found here, nesting in the 9,000-acre wildlife refuge or feeding in the open waters. Atlantic menhaden fish filter the water as they forage, and they are a key source of food for other species. Over 25,000 years, the bay evolved into a network of open water, grasslands, woodlands and shrublands, with a mix of freshwater and brackish wetlands. A hundred years ago, Jamaica Bay was a shallow sandy system, with salt marshes carved up by streams from the ocean.

In addition to being an important habitat, marshes can also reduce storm flooding, according to a recent study of the bay published in the Journal of Geophysical Research, particularly marshes around the edge of the bay, by absorbing the water’s energy and slowing it down.

Today, marshes have been filled in to build neighborhoods and an airport on top of them, shorelines have been hardened, and sand borrow pits and shipping channels have been dug. The average depth of the bay has increased from 5 to 14 feet and the difference in height of high-tide floods has increased by 20%, according to the Journal of Geophysical Research study. The study found that human development was nearly as impactful as sea level rise on increasing high-tide floods.

Storm surge barriers can provide protection from the giant walls of ocean water, but the environmental costs can be heavy, according to a recent scientific review published by the American Geophysical Union. If water from rain is trapped behind the barrier, it can cause flooding. Barriers in London and Massachusetts are being closed so often, they are effectively “sea level rise barriers.” In the Eastern Scheldt in the Netherlands, storm surge barriers altered the flow of sediment so that 63% of the tidal marshes were lost.

“In some ways it seems like we’ve engineered ourselves into these problems,” said Brett Branco, executive director at the Science and Resilience Institute at Jamaica Bay. “And then we try to engineer our way out of them.”

Sea levels have already risen about 18 inches in New York City in the past century and a half, drowning the marshes. Were it not for the neighborhoods built up around it, the marsh would naturally evolve and adapt to the tides and the storms.

“The problem is that the whole bay is spoken for,” said Don Riepe, a neighbor of the Toborgs and guardian of Jamaica Bay for the American Littoral Society, a conservation group. “So if my house and all these houses weren’t here, there’d be marshes here. And as the tide got higher over time, the marshes would move. But they can’t move.”

Over 2 million gallons of combined sewer overflows enter Jamaica Bay each year according to a 2012 city report. Even the hundreds of millions of gallons daily of partially treated sewer water still contain high amounts of nitrogen. Normally nitrogen is a vital nutrient to the salt marshes, but if it’s available in excess, the marshes’ roots don’t reach as deep into the soil, making them more vulnerable to erosion.

“When (the gates) are closed, there’s no exchange of sediment or water,” said Catherine Seavitt Nordenson, a chair of the department of landscape architecture at the University of Pennsylvania and author of “Structures of Coastal Resilience.” “You’re basically filling up a bathtub.”

The Army Corps’ approach

Over a decade ago, the storm surges from Superstorm Sandy reached over 9 feet in lower Manhattan and killed 43 people. Almost 2 million people went without power. Since then, people like the Toborgs in and around Jamaica Bay have raised their homes with federal help to deal with sea level rise and possible future storms.

“Storm surge … erosion, and intense rainfall events … constitute a threat to human life and increase the risk of flood damages,” the Army Corps stated in its 2022 environmental impact statement. “As sea levels continue to rise, coastal storms will cause flooding over a larger area and at increased heights than they otherwise would have in the past.”

People are afraid, and the Army Corps has assured people that sea walls and gates are their best chance for safety. For people dealing with constant flooding from high tides, the idea of barriers could provide some relief. The Army Corps has built some of the biggest infrastructure projects around the country, including storm and flooding protections and hydropower. And while they have been responsible for dredging much of the bay, they have also been extensively involved in rehabilitating the salt marshes in Jamaica Bay, depositing sediment onto the disappearing islands.

But local officials aren’t convinced by their latest plan. The city’s Chief Climate Officer Rohit Aggarwala in 2023 called on the Army Corps to create a more holistic plan, requesting they address flood risks like rainfall and tidal flooding. He said the city would not accept “austere floodwalls running through our neighborhoods,” and requested they include nature-based features in the plan, and address underresourced communities.

Nearly 40 state lawmakers sent a letter to Gov. Kathy Hochul and Department of Environmental Conservation Commissioner Basil Seggos in September outlining serious concerns with the Army Corps’ approach. They said the Army Corps has a “myopic focus on flooding from storm surges” that has skewed the analysis toward in-water barriers and ignores tidal flooding, rising groundwater and combined sewer overflows.

Paul Gallay, former president of Riverkeeper and partner to the Environmental Justice Alliance at the Columbia Climate School, said the Army Corps needs “what used to be called a come-to-Jesus moment. And recognize that they need to do what virtually everybody else involved in the study is asking them to do: plan for all the major flood threats, work with the community, not for them, and design solutions that will also help us with some of our other problems in front-line communities.”

In response to criticism, the Army Corps could be changing. The Army Corps said in an email to City & State on Jan. 29: “(The plan) has now shifted its focus to include natural and nature-based solutions wherever feasible. … In southern Brooklyn and Queens, including Jamaica Bay, the tentatively selected plan suggests various actions that align with previous (Army Corps) evaluations. These actions … take into account the significant environmental impacts they may cause, such as altering hydrodynamic flows or extensive filling.” Their email did not include a timeline for how the Army Corps will include more nature-based solutions.

The Army Corps of Engineers has a long history of ineffective and incomplete projects, perhaps most notoriously, the levees that failed during Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. But Gallay still believes in their best intentions. He says the Army Corps’ mission is to protect the region.

“I think that they now will develop the commitment and develop the skills and expertise necessary to make that change,” Gallay said.

The future of the bay

The Army Corps knows there are alternative solutions to building walls, something they’ve been talking about for half a century.

Nordenson's research suggests that creating a new inlet into the bay, while hard to imagine while people live there, would allow sediment to enter and flush out polluted water, allowing the marshes to naturally heal themselves. Nordenson has shared this research with the Army Corps, but her findings were not mentioned in their recent report.

Philip Orton, an ocean scientist at the Stevens Institute of Technology and lead author for the New York City Panel on Climate Change, co-authored a study that shows that filling in channels in the bay could reduce the height of high-tide floods while still allowing for shipping. The Army Corps does not reference this research or his research on Jamaica Bay in their environmental impact statement. Orton has presented his work directly to the Army Corps.

“One possibility is they just aren’t paying much attention,” Orton said. “Another possibility is these ideas are outside of their toolbox.”

For the Toborgs and the people who live in the bay, life continues on as always, in their slice of paradise in the Big Apple. Moving your car at 3 in the morning because of the tides is part of the deal.

“I saw a kid come home from his lunch hour,” Barbara Toborg told me. “He was trying to catch killifish in the street. Because there was water in the street.”

Elias Guerra is a multimedia reporter covering inequality and the environment in New York.

Clarification: Catherine Seavitt Nordenson's full title has been updated.

NEXT STORY: SUNY and CUNY leaders tell lawmakers they need more state aid