Andrew Cuomo

Cuomo promised ‘free tuition.’ Has New York delivered?

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced Excelsior Scholarship, the state’s ambitious financial aid program for low- and middle-income SUNY and CUNY students, in January 2017. But has the state delivered on its promise?

Gov. Andrew Cuomo discussing the Excelsior Scholarship in 2017. Governor Andrew Cuomo/Flickr

Two years ago, Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s free college tuition proposal enticed support from all corners of the Democratic Party. U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont joined Cuomo for the announcement of the Excelsior Scholarship, the state’s ambitious financial aid program for low- and middle-income SUNY and CUNY students, in January 2017. Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton sat next to Cuomo as he signed the bill into law in April 2017 that created the program.

It was an idea that attracted so much attention because the rising cost of college has burdened more students with more debt.

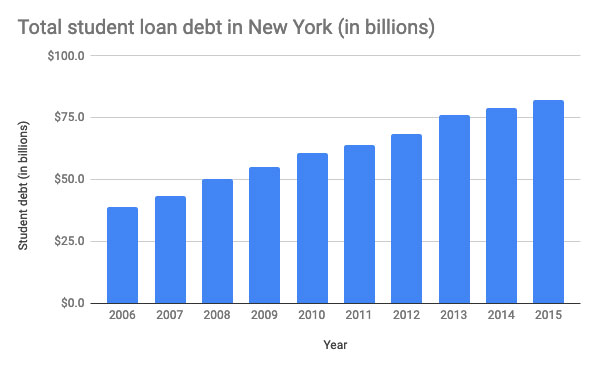

Total student loan debt more than doubled in New York between 2006 and 2015, increasing from $38.8 billion to $82 billion, according to the most recent report from the state comptroller's office. The number of students taking out loans also sharply increased during that time frame, going up 41 percent to 2.8 million borrowers in the state.

Now that the free tuition program is well underway, how is New York doing at mitigating the rise in student debt?

"The student loan debt in New York has reached crisis levels.” - Eli Dvorkin, Center for an Urban Future, director of editorial and policy

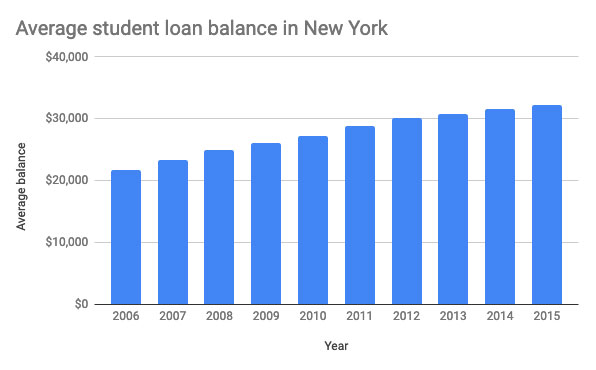

“There are more New Yorkers in debt now than ever before, and the amount that each graduate is indebted has also increased,” said Eli Dvorkin, director of editorial and policy at the Center for an Urban Future, a think tank. “It’s gone from about $20,000 a decade ago to over $30,000 per graduate today. So there’s no question that we’re a part of the national trend and that the student loan debt in New York has reached crisis levels.”

The state has long offered a number of tuition assistance programs to defray the expense of attending its public institutions. These programs, such as the Tuition Assistance Program, Opportunity Programs and the new Excelsior Scholarship, help make New York a leader in keeping higher education costs low and expanding access to low- and middle-income families, according to a November report by the Rockefeller Institute of Government.

TAP is the largest of these programs – and the largest need-based financial aid program in the country – accounting for 95 percent of the state’s total college grant aid. It is aimed at offering direct assistance to working-class New Yorkers attending public universities. TAP awards up to $5,165 a year to qualifying students who have a maximum annual household income of $80,000, and the average award is $3,320 per student. (In 2017, the annual cost of tuition at SUNY was $6,470 and $6,330 at CUNY.)

Glick told City & State that she wants to focus on raising the cap for the TAP award, potentially to $6,000, and reducing the gap in coverage that schools have to fill for poorer students, a need echoed by state Sen. Toby Ann Stavisky, chairwoman of the Higher Education Committee. Stavisky, alongside state Sen. James Skoufis, introduced a bill to increase the minimum TAP award from $500 to $750 and to increase the program’s income cap from $80,000 to $95,000. The Senate passed the bill in January and it is now in the hands of the Assembly. “There hasn’t been an increase in the maximum award in the last five years, so we feel that we should be increasing that as well,” Stavisky said.

Filling in New York’s financial aid gaps has long been a concern among politicians and researchers, and it was one of the problems legislators tried to solve after Cuomo unleashed his idea of free tuition.

“There were some cases where people were paying for school, but they were taking on some student loan debt because it was maybe two or three thousand extra dollars that they had to take on or not finish a class, but if you could just provide an additional fiscal enhancement through tuition, you could actually make sure that they graduated on time,” said Rockefeller Institute of Government President Jim Malatras about the impetus for creating the Excelsior Scholarship. Malatras was a senior official in the Cuomo administration, serving as his chief policy adviser and director of state operations, and he helped draft the Excelsior Scholarship bill.

“We wanted to make sure that people were actually getting through the program and graduating because we had low tuition, but people were still taking on student loan debt and taking on costs, which is sort of bizarre,” Malatras said. “But when you kind of peel the onion back a little bit, it was because people aren’t graduating, and if you could just lower the overall costs of college, you can allow people to finish.”

The Excelsior Scholarship covers tuition costs after other types of financial aid have been exhausted by students taking a full class load, set to graduate on time and from families who met the income requirements. Families making up to $110,000 in the 2018-19 school year were eligible for the scholarship, with the cap set to rise to $125,000 this fall.

The rollout of the Excelsior Scholarship was slightly rocky: two-thirds of the first round of applicants were rejected, many for not taking the required class load of 30 credits per year.

But, the program is only in its second year, and Malatras pointed to early successes like an uptick in applications to New York’s public universities and solid retention rates for scholarship recipients. “I think some of the early indications of what you see under the Excelsior program is that retention rates are up among SUNY students in the Excelsior class,” he said. “So I think the early pieces suggest that it does serve some of its intended purpose.”

More than 20,000 students were awarded the Excelsior Scholarship in its first year, which, like TAP, is administered by the state Higher Education Services Corp. In a January statement to the state Senate Finance Committee and the Assembly Ways and Means Committee, the Higher Education Services Corp. said that student retention was higher among Excelsior students (76 percent) compared to other students (68 percent).

The Center for an Urban Future also analyzed data for the first year of the Excelsior Scholarship and said that the low participation in the program was due, in part, to its somewhat narrow scope and what Dvorkin called “really stringent” requirements. Dvorkin highlighted the course load prerequisite as unfavorable to the lowest income students who may not be able to enroll at 30 credits per year due to other responsibilities, such as a job or taking care of a family member.

State lawmakers have been working on fixing problems that have surfaced with the Excelsior program since it launched. “It’s a really fine program that does need some adjustments – the same way as if you buy a new car, you need a tuneup every once in a while,” Stavisky said. “That’s what we’re going to be doing with the Excelsior program. We’re going to fine tune it so that more students will be eligible and hopefully graduate with less debt.”