New York City

Lax oversight, dubious testing in water tanks pose health risks

Cockroaches, dead pigeons and animal feces could all be in your drinking water – and NYC wouldn’t even know

The drinking water supply for offices of the New York City Department of Sanitation doesn’t even have a roof – just a tattered tarp. Frank G. Runyeon

Shards of decayed wood are all that remain of the roof that once shielded the wooden water tank at 137 Centre St. On a recent morning, raindrops fell through the splintered support beams, rippling the surface of the dark water inside the open barrel. Something green grew on the sides of the rustic exterior. A shredded tarp hung off the top of the tank, like a tattered garment, flapping with each gust of wind. The holes in the tarp were so big that a bird could easily fly into the tank.

This is the drinking water supply for office workers at the New York City Department of Sanitation. Another city agency, which is responsible for the tank, has certified year after year that the entire structure, including the roof, is sound and that the tank has no sanitary defects, dismissing its own 2015 report of E. coli in the water as a “clerical error.”

When asked if there was currently any issue with the sanitary condition of the water tank, a city official replied, “No.”

Despite years of reforms, new data reveal widespread neglect in the thousands of weathered wooden water tanks that supply drinking water to millions of New York City residents. A review of city records indicates that most building owners still do not inspect and clean their tanks as the law has required for years, even after revisions to the health and administrative codes that now mandate annual filings.

There are still many thousands of water tanks across the city for which there is no information at all. The city can’t even say with certainty how many there are or where they are located, much less their condition – even well-maintained water tanks accumulate layers of muck and bacterial slime.

Building owners who do self-report the condition of their water tanks provide suspiciously spotless descriptions on annual inspection reports. These reports include bacteriological test results, but in almost every case the tests are conducted only after the tanks have been disinfected, making it a meaningless metric for determining the typical quality of a building’s drinking water. And regulators have issued dramatically fewer violations in recent years.

The data show that the city reported drinking water tanks on municipal buildings, including the city sanitation offices and several court buildings, tested positive for E. coli, a marker used by public health experts to predict the presence of potentially dangerous viruses and bacteria. Oversight remains lax: It took health officials more than a year to investigate several isolated reports of E. coli in drinking water tanks. After inquiries from City & State, however, officials now say that their own reports were erroneous.

But scientists at the federal Environmental Protection Agency and public health experts consulted by City & State warned that animals can easily get into New York City’s water tanks, that mucky sediments inside the tanks may contain pathogens and that poorly maintained water tanks could be the source of disease outbreaks.

“When you look at waterborne disease outbreaks in Gideon, Missouri, and Alamosa, (Colorado), there are three things that happened,” an EPA water tank expert said of deadly episodes in those places. “If you have sediment buildup, if you have a way that pathogens on animals and insects can get in, and if this sediment is stirred up somehow and is allowed to be used, then you have a real potential for an increase in endemic disease.”

The first two conditions are common in New York City’s neglected water tanks. And so, experts say, poorly maintained water tanks risk waterborne disease outbreaks in the buildings they serve.2

The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, which is responsible for overseeing the water tanks, said the wood tanks are not a cause for concern.

“New York City water is safe, and water tanks pose very little risk to the health of New Yorkers,” department spokesman Chris Miller wrote in an email. “There is no evidence that the water from water tanks raises any public health concern, and there has never been a sickness or outbreak traced back to a water tank.”

However, a department FAQ says that water tanks must be inspected and tested for contamination because “The Health Department wants to make sure that drinking water tanks are free of harmful bacteria that could make residents sick.”

The department does not physically inspect the tanks themselves. Instead, it audits inspection filings, tracks waterborne illnesses reported by doctors and sales of antidiarrheal drugs that might indicate potential waterborne disease outbreaks.

The department said it is “strengthening its water tank oversight” with an online reporting system in order to issue violations to buildings that have previously submitted an inspection but failed to do so that year. Buildings will also be fined if they fail to certify whether or not they have a water tank.

Before 2009, inspections were done on an honor system and testing water tanks was not required by the city. Moreover, as then-New York City Councilman Daniel Garodnick noted, what records did exist could not even be subpoenaed. In 2009, Garodnick sponsored legislation that required inspections, bacteriological testing and public notice of the results on request.

In 2014, several rooftop water tanks tested positive for E. coli and coliform bacteria in water samples taken by The New York Times as part of an investigation that included this reporter’s work. Independent experts were alarmed by the findings. City health officials disputed the Times’ reporting and sampling results at the time and said they were satisfied with their regulations.

But in 2015, health officials reversed themselves and tightened monitoring to require the annual filing of inspection reports with the city. Lawmakers passed legislation last year, which went into effect in April, to further encourage building owners to conduct the inspections and disclose that information to the public.

Has your building been inspected?

Use the interactive map below to find out if your building's water tank has been inspected, and when. (click here to view a full-screen version of the map)

One morning in May, Jonathan Lewin, a water tank cleaner with American Pipe and Tank, rode up the gated freight elevator to a midtown Manhattan rooftop where a drinking water tank had gone uninspected or cleaned for several years. Ascending a ladder to the cone-shaped roof on the wood tank, the horizon widened to reveal an often-forgotten part of New York City’s water infrastructure: a forest of wooden tanks holding aloft a hidden ocean; hundreds of millions of gallons of water.

Lewin lowered his broom and bucket into the tank with a small container of chlorine bleach. Before he could clean the tank, the building should have drained it. Peering into the deep water, it seemed the pipe had clogged. He worried something was stuck in the line.

A pigeon? It wouldn’t be the first time.

In just a year and a half working as a tank man, Lewin has found all sorts of creatures in water tanks, and his experience is not unique. One time, he found a squirrel nest in the crawl space between the roof and the flat plywood cover above the water. Two dead squirrels had drowned below. The building superintendent had seen the squirrels coming and going from the tank and joked that Lewin had found a “squirrel martini.” Another time, company cleaners found evidence of a man living in a tank’s crawl space, apparently the same man police had evicted from a nearby water tank the day before. The vagabond had simply moved his mattress and canned food to the next water tank. Lewin reckons about 1 in 50 tanks he’s cleaned had a pigeon in it.

Lewin’s boss at American Pipe and Tank, Steven Silver, recalled that he once got a call from a building superintendent on Park Avenue who said he didn’t know why the building had no water. He had climbed up to the water tank. Silver recalled him saying, “It’s full … all the way to the top. I don’t understand!” Silver continued, “Meanwhile, I know exactly what the problem is. His conical cover has been shot for two years. They wouldn’t spend the money to replace it. Inundated with pigeons. There’s a dead pigeon floating in the water and it got sucked into the pipe. So, the water’s not going down into the building anymore.”

“We don’t see that a lot,” Silver said of the carcass-clogged pipe. “But we do see pigeons a lot.”

Not knowing what to expect this time, Lewin climbed down to unclog the drain. He was relieved to find the water was just flowing very slowly as the pipes narrowed. He wrenched off the drain pipe, sending dirty water gushing onto the rooftop.

Soon, he was inside the tank, dousing it with buckets of fresh water and scrubbing the wet wood walls with his broom, plowing the thick coat of pulpy sediment toward the drain. The tank was “filthy,” he said as the brown liquid sloshed around his boots. A cockroach corpse floated by. It took Lewin an hour and a half to clean the 15-foot-wide cedar tank.

As Lewin clambered back up the decrepit ladder inside the tank, he saw evidence that animals had gotten into the tank. A 3-inch hole appeared to have been gnawed into a corner of the roof. In the crawl space below the roof, a 12-inch hole in the floor, even larger than the one in the roof, led down to the building’s drinking water. A gray feather sat beside it.

He climbed down, removed his rubber boots, and reported the 3-inch hole in the roof to the building owner. Then, he left.

Tank companies are generally hired to clean and inspect the tank as a package deal. If a repair is needed, the building owner must sign off on it and pay extra for it.

To date, the building owner has not called back about the repair.

“It’s a serious concern if you have a bird or a rodent basically disintegrating in your finished water.” – Environmental Protection Agency water tank expert

The city requires building owners to submit proof of an annual water tank inspection to ensure the tank remains sanitary, but many buildings go years without an inspection, according to city estimates and health department records obtained by City & State through a Freedom of Information Law request in late March.

From 2015 through 2017, 4,578 unique buildings reported a drinking water tank inspection for at least one year. That means fewer than half of all building owners with a water tank inspected it during that time, based on a city estimate of 10,300 buildings with water tanks. Even landlords who followed the rules one year frequently did not follow them every year.

Last year, just 3,527 buildings with water tanks, or an estimated 34 percent, provided proof of a tank inspection, indicating compliance rates may be far worse than the city thought. In April 2015, a health official testified that 73 percent of buildings were in compliance with the annual inspection requirement.

Health officials disagreed with City & State’s calculations, saying they believed the 2017 compliance rate was above 60 percent and that over the past three years more than 75 percent of all building owners with a water tank reported at least one inspection. Health officials did not explain their reasoning.

Still, no one knows for certain how many drinking water tanks there are because the city has never tracked where they are, although officials say they are beginning to do so. The dearth of information has complicated the oversight and regulation of the tanks, which are often the last place New York City drinking water is held before it drains into faucets and shower heads.

With the passage of a law last year that required landlords to file inspection reports with the city, officials hope to create a roster of buildings with water tanks to identify scofflaws, and fine owners who fail to care for their tanks.

When the tightened rules went into effect in 2015, the health department issued water-tank-related violations that resulted in more than $350,000 in fines in the first year, according to data from the New York City Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings. Then, enforcement abruptly dropped off. For the next year and a half, the department only fined a single building $3,750. It wasn’t until the same week City & State submitted its Freedom of Information Law request, in October 2017, that the health department suddenly issued more than $80,000 in fines. But, no more fines were imposed that year.

Just one $500 fine has been imposed this year.

Whether it be a daily shower, morning coffee or a complimentary glass of ice water, a New Yorker uses more than 100 gallons of water a day on average from the city’s abundant unfiltered water supply. City officials crow about its purity, but rigorous scientific monitoring stops at the curb, when it becomes building owners’ responsibility to care for the water inside the city’s timber storehouses.

New York City’s water flows from protected reservoirs upstate through hundreds of miles of tunnels and into city mains, continuously tested for contamination along the way. Once the water reaches a building, however, it becomes the owner’s responsibility to maintain water quality. In most taller buildings, a pump in the basement carries water to a spout at the top of a rooftop tank and another pipe midway down the tank allows water to flow out into the taps below.

The gravity-powered municipal water system only provides enough pressure to reach the sixth floor of most buildings. Since the 1890s, building owners have employed wood tanks on the roof to provide additional water pressure for tenants on higher floors.

In the 19th century, tenements were especially filthy on the upper levels, where water pressure was spotty. To ward off disease, officials required rooftop tanks be built, and as buildings grew taller, immigrant barrel makers filled the need.

Complaints about the tanks’ conditions stretch back more than a century. In 1906, The New York Times ran a letter titled “Water Tanks Not Cared For” in which a writer feared contracting typhoid. He complained that his building’s tank had not been cleaned in over a year and sediment made the water yellowish. In 1950, the Times ran a feature starring “health sleuths” who helped “a petulant housewife bearing a jar filled with water and feathers.” An inspector “found exactly what he had expected” in the water tank, the writer noted. “The tank’s trap door had been blown away and a family of pigeons had come to roost inside.”

A tank typically lasts an average of 25 years, depending on the wood and how exposed it is to the elements. Cedar tanks change color as they age, from yellow to pale beige and beige to a dark, ashen brown that fades into the cityscape.

Inside the tanks, the air is heavy with the smell of wood pulp and must. Specks of dust dance in the air. Shafts of light often shoot between the staves, the wood slowly decaying and flaking off into the water.

Sediment is a common sight in water tanks, steadily accumulating into a muddy layer at the bottom of the tank. Various other types of contamination, such as biofilm and algae, are not unusual to see. Insects and floating debris inside the tank are common, as one might expect in an aging rooftop wooden vessel filled with water. Signs of birds or other animals in the tanks are not so rare, as tank cleaners estimate that they find some kind of animal inside 1 to 2 percent of tanks.

Health officials said they did not respond to the reported E. coli test results until nearly two years later.

City health officials say that the tanks pose little health risk for several reasons: The water is constantly being drawn and replenished, leaving little time for bacterial growth; the water is protected by chlorine; the wood behaves as an insulator that keeps the temperature low; and because water enters through the top and is drawn out of the middle of the tank, sediment and contaminants sink to the bottom.

“It’s extremely unlikely those (contaminants) enter into the drinking water,” wrote Miller, the health department spokesman.

However, two senior scientists at the federal Environmental Protection Agency said they were concerned by what they saw in a series of photographs of rooftop tank cleanings and cited several clear health risks. As a condition of the agency-sanctioned interview, the EPA requested its individual scientists not be named. One is an expert on drinking water tanks. The other is a drinking water toxicologist.

“Using a wooden structure on top of a building is asking for a vulnerable situation,” the EPA toxicologist said.

“This is not a tank that’s sealed from the outside environment. There are all sorts of potential routes for rodents or birds … other flying insects to get into these tanks,” the EPA toxicologist said, reviewing the photographs. “It’s just very vulnerable to contamination from the outside world.”

They noted that the water tanks do not appear to follow best practices. The tanks lack adequate protections like ultra-fine mesh screens on vents and overflow valves, while cracks and openings in the tanks can allow creatures inside, carrying with them potentially harmful bacteria or viruses.

“It’s a serious concern if you have a bird or a rodent basically disintegrating in your finished water,” the EPA tank expert said, referring to the outbreaks, some deadly, that were linked to animal intrusion in large water tanks, including in Colorado, Missouri and the United Kingdom. But for a New York City building with a rooftop tank, it would be harder for health officials to detect an outbreak because a relatively small number of people would be affected at one time. Dangerous microbes would escape the carcass in spurts, not all at once.

Chlorinated drinking water, the experts stressed, is no defense for a decaying pigeon. In those cases, the tanks may be the source of waterborne illness outbreaks the health department never spots.

“If you’ve got one or two people in a building that has 500 people in it, they’re probably going to say, ‘Oh, I just ate some bad food,’” the EPA toxicologist said. “But there still may be a lot of hidden pathogenic outbreaks in these situations given the quality of the tank pictures that I’m seeing here.”

The accumulation of muddy sediment in the bottom of the tanks, which is common, is an incubator for microorganisms, including potentially dangerous ones. Recent EPA research on water tanks around the country has shown that the two most common pathogens in the sediment are mycobacterium, which can cause NTM-PD, or nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease, and Legionella bacteria, which causes Legionnaires’ disease.

As with most waterborne pathogens, mycobacteria and Legionella bacteria principally pose a threat to the very old, the very young and those with weaker immune systems.

Norman Pace, a microbiologist who pioneered techniques to map constellations of bacteria and viruses in unusual environments, said he was especially concerned that water tank cleaners were not properly protected as they cleaned the sludge from the bottom of the tanks.

“It just makes my skin crawl to think of these guys stirring that stuff up without dust masks on,” Pace said. “I would certainly be surprised if there wasn’t a lot of mycobacterium in those sediments … and Legionella.”

When Corinne Schiff, the city health department’s deputy commissioner of environmental health, testified before the City Council in September, Councilman Peter Koo asked her if cleaning water tanks would help prevent cases of Legionnaires’ disease in his district. “Legionnaires’ disease is actually entirely unrelated to drinking water tanks,” Schiff said, adding that investigations of Legionnaires’ cases would not include examining drinking water tanks because the department believes the tanks are safe.

The city’s data on water quality in the tanks is based on samples for E. coli, a microbe that originates in the feces of mammals and birds. But the samples are typically taken after the tank is cleaned and disinfected, which is allowed.

As a result, the water sampling methods are inadequate to provide an accurate picture of water quality in the tanks throughout the year, the EPA scientists and microbiologists said.

“It is a system which is designed to give you the best possible impression but not actually tell you what people are drinking,” said Dr. Jeffrey Griffiths, a professor of public health at Tufts University and a former chairman of the EPA Science Advisory Board’s Drinking Water Committee. “It certainly is self-defeating to be taking an E. coli test at the end of it. It would seem to me you should be taking an E. coli test at the beginning and at the end.”

“We have an active monitoring program for E. coli, which would be one of the bacteria we would be worried about that make people sick,” Schiff said during the September hearing. “We have no evidence, no cases of E. coli we can link to a drinking water tank.”

Out of more than 13,000 tank inspection filings over the past three years, just six reported a positive E. coli test. Nearly all those were in public buildings, including the Brooklyn Central Courts Building, the Brooklyn Appellate Courthouse, the Manhattan Civil Courthouse, the Louis J. Lefkowitz State Office Building, and the Excelsior Building – home to the city Department of Sanitation’s offices.

When E. coli is found in drinking water, a boil water order is required, according to EPA regulations. In a public building, the agency experts said notices should be posted at water sources, such as drinking fountains.

But the New York State Unified Court System appears not to have known about the reported contamination. “I am told by our facilities people that there was never an issue with the water tanks,” said courts spokesman Lucian Chalfen. He directed further questions to the Department of Citywide Administrative Services, the agency that maintains many New York City buildings.

City & State then requested DCAS’ inspection records, which any landlord is required to make available within five business days upon request. Before responding, DCAS filed a series of 2017 reports, months past the filing deadline. When DCAS did respond weeks later, it provided two dozen pages of records that frequently contradicted each other. For example, water test results were repeatedly recorded and certified as accurate months before the tests were ever conducted.

The records showed multiple health code violations, but the health department did not fine DCAS or issue a single violation.

Jacqueline Gold, a DCAS spokeswoman, said the agency has no tank inspection records prior to 2015. Gold also said DCAS has no lab results for a bacteriological water test prior to 2016, even though DCAS provided a spreadsheet printout that appears to show all five buildings tested positive for E. coli in December 2015.

Gold said that DCAS’ multiple reports of E. coli positive tests in 2015 were a “clerical error.” But health officials also said they did not respond to the reported E. coli test results until nearly two years later, when they contacted DCAS last fall – about the time City & State requested the city data.

Safe or not, security officers at the entrances to three of the court buildings universally recommended against drinking the water. A few years back, several officers in two different court buildings said their bosses told them not to drink the building’s water and instead drink bottled water provided to them. There was no formal warning about the building’s water, they said, but it was common knowledge that you don’t drink the water.

Visits to two of those court buildings, located in Manhattan at 80 Centre St. and 111 Centre St., found functioning water fountains throughout the buildings, including outside hushed jury rooms and in bustling Housing Court hallways. On the 11th floor of the Manhattan Civil Courthouse, a woman said the pipes are just old. “You can taste it. It won’t hurt you,” she said. The water had a metallic, musty flavor. Inside the Lefkowitz Building, where well-dressed couples milled about the Manhattan Marriage Bureau and lawyers trudged to the district attorney’s office, a small shop sells coffee that the shopkeeper said was made with the building’s tap water. A floor above, a state court officer with a desk not far from a water fountain said no one ever told him about E. coli or a problem with the drinking water. He’s been drinking from that fountain for years, he said.

Two city Sanitation Department employees in the Excelsior Building at 137 Centre St. – whose dilapidated drinking water tank sits exposed to the sky – also said people drink the tap water.

The only other building that self-reported an E. coli positive test result was 114 W. 70th St., an Upper West Side co-op, also in 2015. City & State requested the inspection records from Lisa Jensen, the building manager, but she said the co-op board refused to provide them – in violation of the city health code. The board would only make them available to tenants.

City health officials did not notice the E. coli report submitted by the co-op until they came across it while they were reviewing cooling tower inspections. The city did not issue any violations to the building, despite the co-op failing to notify the health department within 24 hours, as required. Subsequent tests were E. coli negative, health officials noted.

While the city’s new water tank inspection data provides a limited directory of buildings with drinking water tanks, it also catalogs the observations of water tank inspectors. But a review of that data found that the observations entered in the reports were at odds with the expectations of scientists and water tank cleaners who have spent years building, scrubbing and repairing these wood tanks.

Looking only at the data, the water tanks appear impossibly clean.

Sediment, which is universally acknowledged as common, even in well-maintained tanks, was only reported in 1.8 percent of all tank inspections. When a water tank company representative was listed as the contact person for the inspection, those inspections virtually never reported sediment or any other sanitary defect.

Henry Rosenwach, the vice president and heir to the multigenerational Rosenwach tank business, is the contact person for more than 5,800 of the roughly 13,000 inspection reports filed from 2015 through 2017 – far more than any other individual. Yet, not a single inspection with his name on it reported the presence of sediment or any other sanitary issue in a water tank.

“The answer might be, very quickly, is that they clean the tank – and then observe it. There’s no sediment!” said Philip Kraus, president and CEO of Fred Smith Plumbing & Heating Co. He laughed. “That’s probably what happens.”

Rosenwach executives did not respond to phone calls, voicemails or emails requesting an interview to talk about their inspections.

The law does not specify exactly when the observations should be made. The two other major tank cleaning companies said they make their observations after the tank is cleaned.

“When we get there, yes, there’s sediment. There’s almost always sediment at the bottom. The point is that we get rid of it,” said David Hochhauser, who owns legacy tank company Isseks Brothers Inc. with his siblings.

“I think the point of when they’re saying, ‘Do you observe these things?,’ it’s after the fact. Not before the fact,” Hochhauser said of the city inspection form. “By getting rid of it, you’re attesting to the sanitary quality of the water.”

In contrast to Rosenwach’s observations, inspection reports where Fred Smith Plumbing is listed as the contact were more in line with cleaners’ descriptions and City & State’s observations of water tanks before they are cleaned. But tank cleaning is only a minor part of Kraus’ business, which averages about 80 tanks a year.

“We look at the tank, and if we see sediment, we report it – and then, of course, we clean it,” Kraus said.

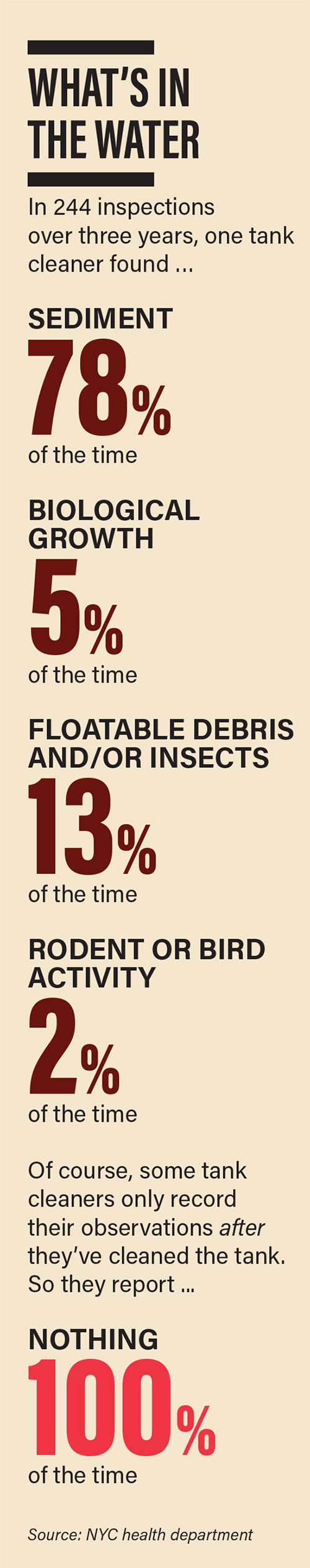

Fred Smith Plumbing reported sediment was present 78 percent of the time, biological growth 5 percent of the time, insects and/or floatable debris 13 percent of the time, and rodent or bird activity 2 percent of the time.

Very few buildings self-reported bird or rodent activity in their water tank inspection observations – just eight buildings in three years. Those that did included an upscale cross section of New York real estate: two stately residences with uniformed doormen, one with a marble lobby on Fifth Avenue and another off Central Park West that features wood-paneled elevators; a midtown Manhattan building with a popular sushi restaurant; a Diamond District building with a Pret A Manger at street level; a newer apartment building on the Upper East Side that shares its plumbing with a medical center.

Self-reports of such unflattering sanitary defects may be more a hallmark of the inspector’s honesty and interpretation of the city rules than any indication of a building’s cleanliness when compared to other buildings. More notable is what’s missing from most of the inspection observations: descriptions that match the typical conditions of water tanks.

“It’s not brain surgery. There’s no reason why this system can’t be made safe.” – Eric Goldstein, New York City environment director for the Natural Resources Defense Council

At the city Sanitation Department’s building at 137 Centre St., a series of inspection reports appeared to directly contradict plainly visible problems.

Atop the building, City & State observed a wooden water tank with a nearly nonexistent roof, partially covered with a torn blue tarp. The tank was filled to the brim and the water was clearly visible from a distance. A blue tarp has covered the tank since at least June 2014, according to a series of Google Street View images. Hochhauser said the neglected vessel is likely the drinking water tank he built in 1981. “It’s in deplorable condition,” he said. “If it’s an active domestic water tank, that’s shocking.” Nevertheless, in water tank inspection reports DCAS employees repeatedly certified, under penalty of perjury, that the tank had no sanitary defects.

Michael Nettleton, the DCAS inspector in 2017, confirmed that the wood tank on the sanitation department’s building contains drinking water, but had a hazy memory of the inspection.

“Yeah, no, I probably may,” Nettleton said when asked about the inspection report that bore his signature. “Last year. I may have looked at it, yeah.”

Another oddity in the paperwork is that the inspection date is noted as March 2, 2018, but the date next to Nettleton’s signature reads March 17, 2017.

“Let’s just say there’s something that sounds a little fishy about that data,” said Eric Goldstein, New York City environment director for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

“Clearly there is a need to tighten up on inspections and enforcement and the City Council should move to fund an independent study that analyzes the risk from current water tank maintenance practices and summarizes best practices throughout the industry, which would include annual cleanings,” Goldstein said. “This is a statutory gap and a problem with enforcement. It’s not brain surgery. There’s no reason why this system can’t be made safe.”

The EPA scientists and health experts agreed that New York City’s wood drinking water tanks warrant further research, both for the potential health risk they pose and because they have never been subjected to scientific investigation. They pitched a range of ideas and avenues of inquiry – from sampling possible molds and fungi in the tanks to monitoring the health of building residents. It’s unexplored territory, they said.

In the meantime, the largest and most densely populated city in America is served by these little understood and poorly maintained wooden reservoirs hovering above the cityscape, as they have for more than a century.

“It sounds like a system that has got lots and lots of flaws to it and potential for public health impact,” said Griffiths, the former EPA drinking water committee chairman. “The idea that they are finding pigeons in 1 out of 50 tanks? Come on. That might have been OK in 1900, but it’s 2018 now.”

With reporting by Ben Jay.