Editor’s note: This article is the first in a three-part series examining how and why New York’s nursing homes too often fail to keep their residents safe. Read the second part here.

New York’s nursing homes have received failing grades from watchdog groups for years. Now, recent statistics and reports suggest the state’s nursing homes are getting even worse as for-profit operators gain a larger share of the market and oversight agencies struggle to provide quality control.

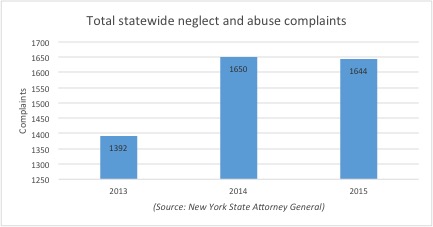

Reports to the New York Attorney General’s office, which investigates and prosecutes criminal and civil cases related to nursing home care, were up “markedly,” according to an official in the office’s Medicaid Fraud Control Unit. Between 2013 and 2015, allegations of abuse and neglect climbed from 1,392 to 1,644, or about 18 percent.

While officials caution that the spike may be the result of better reporting at nursing homes, the figures may also be indicative of a worrying trend.

Many studies show that for-profit nursing homes generally provide lower quality care when compared with nonprofit or government-owned homes, according to Dr. Charlene Harrington, professor emeritus at University of California San Francisco. She is among the leading researchers on nursing home quality, chronicling the endemic problems in for-profit facilities.

It is a long documented trend. A 2009 study from the federal Government Accountability Office found that the worst nursing homes in the country tended to be run for profit.

“The for-profit large chains are the worst in terms of both staffing and quality,” Harrington said. “New York has been sort of unique in keeping out a lot of national chains, but I know New York has a lot of regional chains. The real growth has been in these chains. And the chains have definitely been problematic.”

The damage to quality care is typically seen in two categories: a higher number of deficiencies and short staffing. Since higher staffing correlates with healthier residents, fewer staff members means just the opposite. In other words, there often just aren’t enough nursing staff to provide decent care for the residents.

“Nursing homes are labor intensive, so basically, they're about staffing. And the main place these companies can cut their cost is having fewer staff with wages and benefits and have less well-trained staff,” including critically-important registered nurses, Harrington explained. “They cut corners on all of that. That's the main way they make their money.”

In the past year alone, several grisly cases of abuse and neglect have come to light in New York. In one case, a nurse aide at West Lawrence Care Center in Far Rockaway allegedly pummeled a bedridden 80-year-old, leaving her battered, black-eyed and ultimately hospitalized.

But while cases of outright assault against elderly nursing home residents are shocking, it’s comparatively rare, said Paul Mahoney, deputy chief of the state attorney general’s Medicaid Fraud Control Unit that investigates and prosecutes such crimes.

“Many more of the incidents of abuse and neglect involve activity in which no one was intending to create a bad outcome. But shortcuts were taken – due to a lack of oversight or staffing – and something goes wrong,” Mahoney said. “Then, someone doesn't handle it properly. What is an accident becomes a crime, because instead of giving a person care for the accident, they cover it up.”

Mahoney pointed to perhaps the most egregious case his office prosecuted in the past year, in which a nursing home worker at Medford Multicare Center for Living, Inc. on Long Island was convicted of criminally negligent homicide after she failed to connect 72-year-old Aurelia Rios to her ventilator while she slept, ignoring a doctor’s order. Several nurses ignored alarms for two hours warning that Rios had stopped breathing. After her death in 2012, administrators and staff falsified records and lied to the family for years.

Aside from criminal indictments, what both the Medford case and the West Lawrence case have in common is that they are both for-profit operations.

In 2006, for-profits owned half of all New York nursing homes. In the last decade, however, for-profits bought up 20 percent of all government and nonprofit nursing homes in the state, increasing for-profit nursing home ownership to nearly 60 percent of the state's total, according to an analysis of government records by City & State.

While the majority of New York's nursing homes are now run for profit, those homes are more than twice as likely to hold the lowest federal rating (1-star) as those that are nonprofit or government run. In fact, among the state’s 371 for-profit homes, 92 of them – or 1 in 4 – ranked among the state's lowest-quality facilities.

A report by ProPublica last October showed that New York’s largest for-profit chain, SentosaCare, LLC, has successfully expanded its ownership in recent years despite a record of repeat fines, violations and complaints of deficient care among its 25 facilities.

“In my experience, abuse and neglect is far too widespread in far too many facilities," said Brian Lee, executive director of the nonprofit advocacy group Families for Better Care. While he allowed that the increase may be attributable to improved reporting, he said, “It could be that the abuse and neglect was there all the time and it’s just finally getting found out.”

New York state has over 105,000 elderly people in nursing homes, according to federal statistics, more than any other state in the country, but it has consistently received some of the lowest marks nationally.

"You guys have some of the worst nursing home care I've ever seen," said Lee, who previously served eight years as Florida’s state long-term care ombudsman in a federal program investigating complaints and advocating for nursing home residents. “Some of those nursing homes are little shops of horrors.”

Lee’s organization analyzes government statistics and releases nursing home report cards for each state. When the rankings are released later this month, New York will receive an "F" rating for the third year in a row while ranking a dismal 44th overall. According to the forthcoming report card, 95 percent of the state’s facilities were cited for one or more deficiencies (a 3 percent increase over the previous year), while nearly two-thirds failed to score an above-average health inspection rating.

The general public often fails to understand the problem, Lee said. “Yes, people die in nursing homes because they have serious ailments and that's to be expected,” Lee said. “But to see how many are being neglected to death? It's just insane. It should not be happening in our country.”

Advocates, researchers, and watchdog groups point to short-staffed government overseers as another key reason for the proliferation of poor quality nursing home care in the state.

A recent report from the New York state comptroller’s office found that although the state Health Department, charged with enforcing minimum care standards in nursing homes, was “generally meeting its obligations,” the enforcement division was so inefficient that there were delays of “up to six years between when the violation is cited and the resulting fine is imposed.” The delays undermined incentives for nursing homes to clean up their act, particularly repeat offenders, the report noted.

A spokesperson from the comptroller’s office said the problem appeared to stem from a single part-time employee who was saddled with both the obligation to process the fines for all the nursing homes in the state as well as conduct his own investigations.

When asked for comment on the comptroller’s findings, a New York State Department of Health spokesperson said the report “found DOH to be in compliance with federal regulations governing the inspection of nursing homes, and that the agency acts quickly on serious complaints. A new enforcement process was implemented by the DOH Nursing Home Division in April 2015 and we are continuing to work to ensure that fines are assessed in a timely manner.”

Nevertheless, investigators at the attorney general’s office say more could be done.

“There is room for more oversight,” said Mahoney, the deputy chief of the state attorney general’s Medicaid Fraud Control Unit. “The Department of Health could use more enforcement staffers.”

But the problems at the Health Department go beyond short staffing, critics say. They believe the nursing home regulatory system suffers from deeply flawed oversight and poorly implemented policies that ultimately put frail and vulnerable New Yorkers at risk.

Richard Mollot, a leading advocate for nursing home residents at The Long Term Care Community Coalition, said the state Health Department has abdicated its role as the state agency responsible for enforcing quality care in nursing homes.

“In essence, they don't see their role as a regulatory agency, even though they are a regulatory agency,” he said. “That's really what the problem is.”