New York City

Remembering life five years ago when COVID-19 stopped New York City

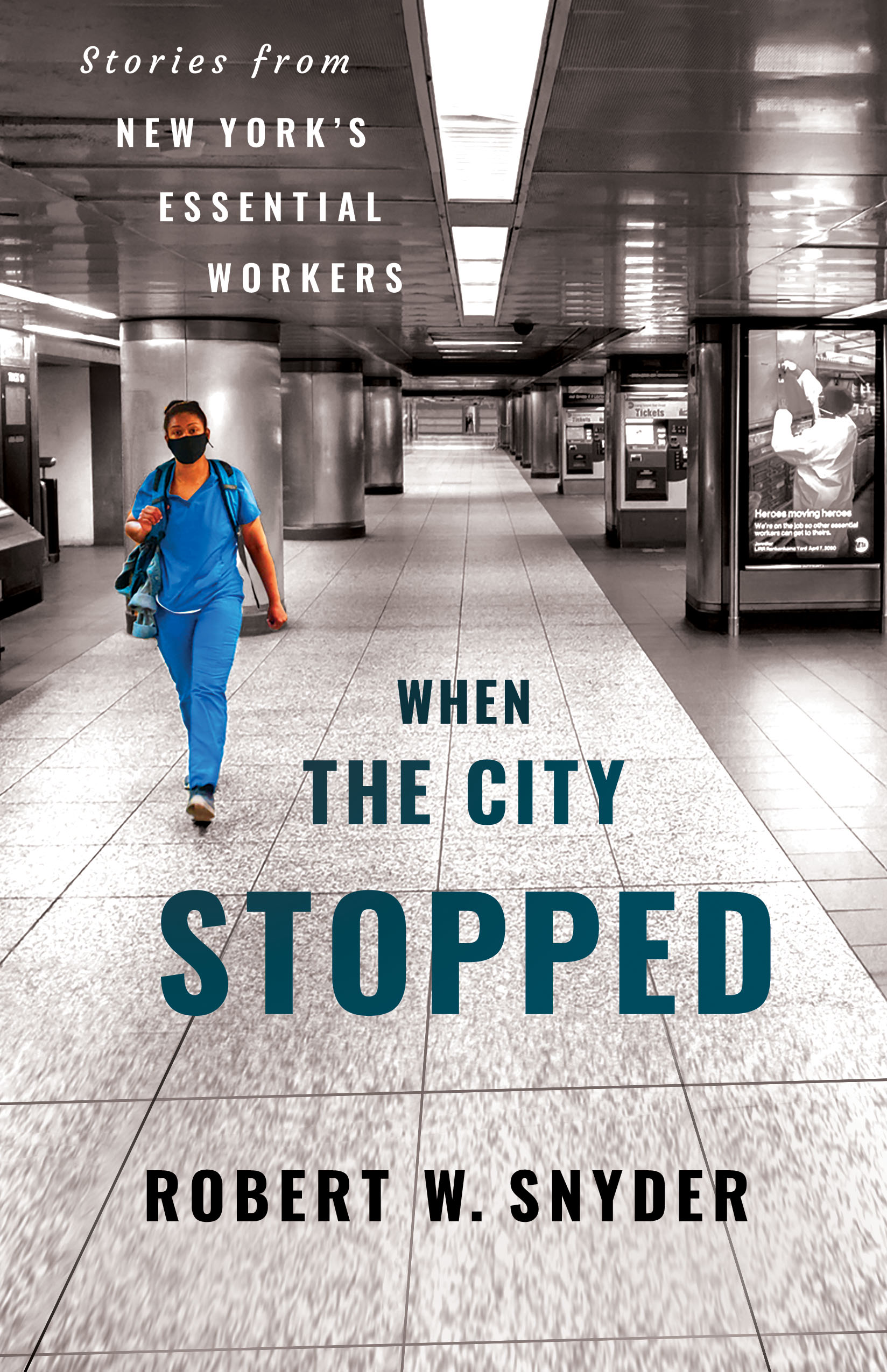

A new book from Manhattan Borough Historian Robert W. Snyder collects dozens of interviews from first responders.

Hospitals brought in refrigerated trucks to serve as temporary morgues at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Bryan R. Smith/AFP via Getty Images

Five years ago, the city that never sleeps came to a standstill. Home to one of the first major coronavirus outbreaks in the U.S., New York City shut down in the second week of March 2020. In the weeks and months that followed, the city’s hospitals became overwhelmed. Hospitals brought in refrigerated trucks to hold dead bodies and the crisis caused morgues and funeral homes to be backed up. In order to chronicle and remember what the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic felt like, archivists and historians spoke to people in all five boroughs who served on the front lines of the health battle against the coronavirus. Manhattan Borough Historian Robert W. Snyder collected dozens of interviews in “When the City Stopped: Stories from New York’s Essential Workers,” out March 15, 2025, to serve as a resource for future generations.

From When the City Stopped: Stories from New York's Essential Workers, by Robert W. Snyder, a Three Hills book published by Cornell University Press. Copyright (c) 2025 by Robert W. Snyder. Used by permission of the publisher.

Interview conducted by NYC COVID-19 Oral History, Narrative and Memory Project at Columbia University

Phil Suarez was born in France, has lived in Spain, and resides in Easton, Connecticut. A paramedic in New York City with more than 25 years of experience, for the past decade he has worked in Harlem and Washington Heights. He stayed at his job during COVID-19 despite its risks.

I’ve always worked in impoverished enclaves of New York City, immigrant communities.

As an immigrant I can relate to them better. I find them to be sometimes more real than more upscale areas like the Upper East Side where people may be more snobbyish or name dropping. I just find the underserved communities need the help. They need people that are probably a little more understanding of how they got there, what they may be going through. It probably comes from my background as an immigrant myself.

I’ve been doing this a long time. For me, it’s a very easy job.

I’m drawn to it because an old partner of mine that’s a writer said, “We knock on their doors, and they open their doors to us.” For that half hour, we’re an integral part of their crazy world, whatever that may be. And it’s really crazy. It’s almost like voyeurism. And it is addictive. Twenty plus years into this, I can still be stunned. Most of our calls are very routine. And then you have your more chaotic scenes where there could be a trauma like a car accident, somebody stabbed, shot, for instance. You can go from doing nothing, from zero or five miles an hour to, all of a sudden, being like eighty miles an hour in this chaos. That’s what our forte is. Most of us that have been doing this for a while, we kind of thrive in that chaos. I can’t imagine working a controlled environment.

Preparing for the surge

I started preparing myself and with my supervisor we kind of took the reins. We started hoarding the PPE [personal protective equipment] as much as we could. Stashing it. People were kind of panicking and if they saw a roll of toilet paper, they would grab it. [laughs] If they saw N95s, they would grab them. So the hoarding became a problem ’cause you want to have stuff available for everybody.

I’ve worked many disasters and stuff like that. I was probably a little bit better prepared, and so saw that coming, I knew I would be good to the best of my abilities as far as PPE. That I would have enough for foreseeable future. And that’s being diligent.

And all of a sudden, for the better part of three weeks, it seems like everything that we did was COVID-19. I think 98 percent of our call volume was all COVID-19 symptoms. All of a sudden it was before us. Came in very violent.

Everything I’ve done, I tried to take what I call a calculated risk. I was an avid mountain biker. I was a mountaineer, a rock climber, and stuff like that. So everything I did, I tried to do a calculated risk. How much risk am I taking here? Am I okay with it? What are my chances of really getting hurt?

I approached everything through my knowledge base. I told my supervisors and bosses I will keep coming to work as long as I have no fever, and I have a N95 to wear for the shift. The day I have a fever or I don’t have an N95, I will not come to work. And that was my red line. There has to be a red line.

My personal feeling is that the health officials didn’t take into consideration the risk that we were taking and the repercussions of those risks because we expose ourselves, we expose others.

Seeing EMTs without masks or without proper gear

I’m a paramedic. We’re the highest level of care in prehospital. Then there’s the EMTs that are basic. And often times, we back them up.

I was taking as many precautions as I could. And I would go into their ambulance and see that they had no mask on. I would pull them aside.

“Hey, where is your PPE?”

“Oh, no. No. He’s got back pain.”

I said, “No. He’s got COVID-19. Back pain, mostly likely, is COVID-19.”

At times, some of the EMTs or crew – some of the other crews that may have known better – I actually yelled at some of them. I would take them aside and just like, “What are you – you got to be smarter than this.”

What was happening in March and April of 2020

We work in an immigrant community where there’s six, eight people living in a small apartment. And some of these apartments we go in there, and you’d have half or three-quarters of the home exhibiting flulike symptoms, which most definitely were COVID-19. So we’re not going to bring them to the hospital. There’s risk of them infecting others. And health care workers. They’re just going to be sent home. And was it ideal, looking back? Probably not. But it was what we had back then.

I carried a certain amount of guilt when we started realizing that some of these people that were having symptoms like low-grade temperature and mild shortness of breath within three days would go into the storm, and many ended up in life support or some of them succumbed to the virus.

But it’s what we had on hand. It’s what we knew. There was no alternative.

So I did my best to take my time in the homes and tell them about self-care. It seems that we have lost the ability to self-care over the years. Nobody has Tylenol anymore. Nobody knows to hydrate with water, not soda. Or to isolate yourself from the healthy.

I’d go into homes and the sick were sitting next to the healthy on the sofa. So that was kind of frustrating to see the public not doing their part, even the basics of self-care. And so I would tell them. Go take a shower. Hydrate. Eat good food. Build up your immune system. Stay away from fat and sugar and stuff like that. And drink a lot of water. Take Tylenol if you need to.

I made it a point to tell them to walk thirty feet. If they could walk thirty feet, just keep doing what they’re doing. But once they can’t walk a certain amount, you have to assume that they’re desatting, that their oxygen saturation may be dropping. Then you need to be hospitalized. So I felt that was the best I could do with the information and the tools we had on hand.

People were scared to go to the hospital. As a matter of fact, I had to convince people to go to the hospital because they were so scared of COVID-19. I would tell them, “You most likely have COVID-19. So you’re not going to recatch it. You have every symptom of coronavirus. You need to be hospitalized.”

A day to remember

My worst day was April 6 or something like that. In one day, I had a fifteen-year-old, a twenty-five-year-old, a forty-two-year-old, and a fifty-six-year-old in cardiac arrest.

And they all died except for the twenty-five-year-old. The fifteen-year-old was difficult, but I knew she wasn’t going to make it.

It was 6:00 a.m. I logged on to our computer in the ambulance and we get what’s called a sprint, basically a transcription of the 9-1-1 call. And it says, “Fifteen-year-old, cardiac arrest, CPR in progress by family.”

And I told the dispatcher, “You’re reading the same thing as I’m reading. It’s a child in cardiac arrest. Can you send me somebody? I’m coming from a distance. I’m coming from Manhattan.”

And they’re like, “You’re solo. Do your best.”

So we hauled over there to the Bronx. It’s a fifth floor walkup. We load up fifty pounds of gear, go up five flights of stairs.

At that point, fire got there. And she was asystolic. [Her heart had stopped beating.] We tried to work her up. I was very aggressive, obviously. And the best we got was a PEA, a pulseless electrical activity, briefly. Then she went right back into asystolic.

I know there was nothing more I could have done. But it still – fifteen years old. Obviously, it weighs very heavily on anyone. And the family was there. It was just very, very traumatic. But the rest of the day didn’t get any better.

And oddly enough, three of them that I had, they had the same scenario. They had these low symptoms. And they were about to go into the shower. And then they went into cardiac arrest. And all of a sudden they would just drop dead.

And this twenty-five-year-old was the same thing. It was bizarre. I don’t know why.

The twenty-five-year-old, he had just gone down. I wanted to give him every chance possible, so I’m like, “You know what? I’m just going to do a endotracheal intubation” [insert a tube into his windpipe to deliver oxygen], which is riskier obviously. And we worked him up for about fifteen minutes and got him back. How he did, I don’t know. It was just too many patients to follow up on. But I think it was pretty promising. But I, unfortunately, don’t know his final outcome. I hope it was good. I told myself that it was maybe good.

So that was my worst day. I was averaging about three cardiac arrests a shift, which is unprecedented. That day was four, but that day made it worse. Just the ages. It was such young people. And that just puts a lot into perspective. It’s so frustrating to read and to hear what we hear knowing what we saw and witnessed.

Being in harm’s way

With COVID-19, I have to say, at first, I think I was going to get it, and I was likely going to die. And that was scary. I think that’s probably what caused a lot of anxiety. All these people are getting it. I’m not special. [laughs] And I’m a male. I’m well into my forties. I’m probably going to get it. And I’m going to die. Or be really messed up from it. And that was hard. That was one of the hardest things I’ve probably had to personally dwell with in my life.

I talked about it with my wife. Talked about it with myself a lot. And I just kind of liked my job. I know some people kind of stopped working because the risk was too much.

We’re not special. We’re not heroes. But this is our job. I couldn’t live with myself if I abandoned my job in its most dire moment. It’s what we chose to do. For better, for worse, we mitigate the risk, and we try to do our job. And that was what I told myself.

At the end of my shift, I would get in my car. I would take a bottle of Purell and literally rub it all over my face, shove it up my nose, in my ears, my hair. For the first week or so, we had Lysol, so we would spray ourselves down with Lysol. And if it was on us, at least try to kill it before you go home.

I would drive home for about an hour. Sometimes I would find myself with my mouth gaping open just staring. Just kind of trying to process what the last eight, sixteen hours have been like. It’s truly a profound moment.

I would get home, go in the garage, strip down to my birthday suit. My wife would be out there with a garbage bag, put all my stuff in there, then she would take the clothes, put it in the washing machine. And I would go into the shower and literally loofah five layers of skin off of me. I mean literally clawing my skin off to hopefully get rid of the stuff.

Anxiety

I had a huge amount of anxiety, which is something I’ve never really experienced before.

I wasn’t sleeping much. I was constantly thirsty. I was barely eating. I had no appetite. I was so thirsty. I could not drink enough water in a shift. And thereafter, when I was reading stuff, I started realizing these are all signs of anxiety. These are all signs of stress.

I tried to come home and decompress. Kind of just shut that out. I stopped reading a lot of media stuff, especially social media. That I avoided like a plague itself. I read just headlines. And then when I would come home, I would make it a point that with the family just try to talk about COVID-19 or get it out of your system. Talk about it. And then talk [laughs] about something else. But it was difficult. It dominated our whole lives for that time. It really did. I’m sure I’m not alone in this.

Sources of information

We had nothing. [laughs] And even if we did, I would take that with a grain of salt. It’s like reading the news nowadays. You really have to dig around five, six sources. I double check my sources.

I only read what I feel are trusted sources and try to just drown out all the misinformation that is so prevalent [laughs] and so toxic. We really don’t get [laughs] memos, meetings. Nothing. It’s incredible but not surprising. [laughs]

Did the city provide services or debriefings?

No. No. No. [laughs] No. I had no expectations of it either. We never have. [laughs] As like 9/11. Just get back to work. [laughs] Sometimes – I always felt that that’s one of the bad things of our profession. There’s no sort of like decompression like somebody steps in.

But I do feel that it should be there for the psychological wellbeing of anybody, whether it’s a social worker, a doctor, nurse, whoever. We’re human after all. We have to process this stuff.

NEXT STORY: This week’s biggest Winners & Losers