Personality

‘Just Tolled’: Public transit enthusiasts celebrate start of congestion pricing

A group of friends borrowed one of their parents’ cars to try to become the first people tolled under the new congestion pricing program just after midnight on Sunday.

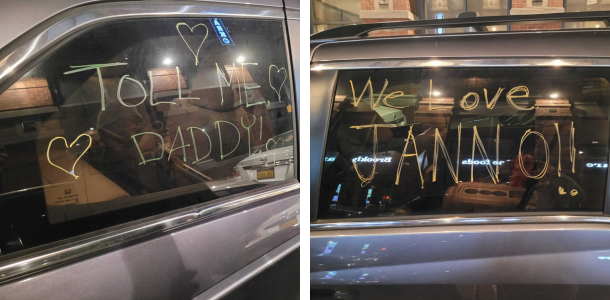

A festive minivan adorned with the words “Just Tolled” drove across 61st Street just after the new congestion pricing program went into effect at midnight on Jan. 5, 2024. Rebecca C. Lewis

At 11:59 p.m. on Saturday night, a group of seven friends piled into a Honda minivan at 61st Street and West End Ave. in Manhattan. The vehicle was decorated to look like it had just come from a wedding, with cans adorning its bumper and the words “Just Tolled” written on the rear windshield. Right after the stroke of midnight, the group drove the van past the border of the Central Business District that starts south of 61st Street. They had just become among the first people tolled under New York City’s long-awaited congestion pricing program.

About a dozen transit-loving friends in total arrived for the occasion, which City & State learned about by chance, although not all of them were physically in the van. They gathered at around 11:30 p.m. to get the car and themselves ready, excited to become the first ones tolled. “We could have just celebrated that it was happening, and instead, we made a little fun event for it,” said Émilia Decaudin, a former Queens district leader and 2024 Assembly candidate who was part of the group. “It's an excuse to see each other. It's an excuse to show the world that there are some people that really do like this proposal and think that it's going to make our city a better place.”

With seconds to go until midnight, they waited at a red light across the street from the cameras that would record their license plate. They asked the car next to them to wait a few seconds after the green light. The driver agreed, and when the light changed, the Honda drove past the cameras, honking as it went, cans rattling behind it. One person held a sign through the sun roof that read “E-Z Breezy Bondable.”

The plan was the brainchild of Adam Brodhim, a member of Community Board 7 in Manhattan. He had been waiting for the tolling scheme for a long time. “I remember one year when Bloomberg was running for mayor,” Brodhim said. “He was at my subway stop on the way to high school when I was taking the train, and I was like, ‘Are we gonna get congestion pricing?’” Obviously, it would take quite some time after former Mayor Michael Bloomberg to get the program going.

Brodhim borrowed his parents’ car with the promise that he would repay the cost of the toll once the bill came. With cameras and an E-ZPass reader recording their trip at midnight, that will be $2.25 – cheaper than the cost of a subway or bus ride at $2.90.

Most of the time, between the hours of 5 a.m. and 9 p.m. on weekdays and 9 a.m. and 9 p.m. on weekends, drivers with an E-ZPass will now be charged $9 to drive into the Central Business District – which the MTA is calling the “Congestion Relief Zone” on signage – at 60th Street and below. The toll is higher for drivers without E-ZPass. Trucks will also have to pay more, with small trucks being charged $14.40 and large trucks facing a $21.60 toll.

The MTA is expected to increase the toll in the coming years, up to $12 for most drivers by 2028 and $15 by 2031. But drivers making less than $50,000 a year can apply for a half-price discount after getting tolled 10 times in a month, and most drivers who enter the Central Business District by one of four tolled tunnels will also get a $3 credit.

The congestion pricing program is meant to raise $15 billion for the 2020-2024 MTA capital plan for crucial infrastructure repairs and improvements, like accessibility projects, as well as expansions like the next phase of 2nd Avenue subway. MTA officials expect the raw tolls to bring in roughly $600 million a year – recurring revenue that will be bonded out for the rest of the money. The program is also meant to reduce congestion in the busiest parts of Manhattan to speed up traffic for first responders, buses and those people who still need to drive.

Originally signed into law as part of the state budget in 2019, the program was meant to begin at the end of June after a lengthy process to set it up. But Hochul made a sudden and last-minute decision to pause it, citing concern that the original $15 price tag was too high for many New Yorkers struggling with sky-high costs of living right now. After months of uncertainty, Hochul announced in November that congestion pricing would return at a reduced price. The governor touted the lower fare as an affordability victory for drivers, but most people who were originally opposed to the tolling scheme didn’t see it that way and continued to fight it.

Up until Friday afternoon, the MTA didn’t actually have a guarantee that they could flip the switch on Sunday. Several parties, including the state of New Jersey, filed lawsuits to try to kill congestion pricing and asked judges to issue emergency restraining orders to delay its implementation as their cases play out. The final greenlight to move ahead with the program only came Friday evening, when a federal judge in Newark rejected New Jersey’s last attempt for a preliminary injunction to halt the Jan. 5 start to congestion pricing. An appellate court upheld the ruling on Saturday.

Brodhim and Decaudin’s friends were not the only people who attempted to be the first ones tolled at midnight. On the other side of town on Lexington Ave., Greenpoint resident and safe streets advocate Noel Hidalgo joined a larger and publicly advertised group of transit activists celebrating the start of congestion pricing. The front of his car had a banner that dubbed it “The First Car.” Although an anti-congestion pricing protester caused a minor delay, Hidalgo said he managed to drive into the Central Business District just after midnight.

Hidalgo is the father of a “medically complicated” child who needs frequent doctor visits that require a car. Although opponents of congestion pricing have argued that the toll will negatively impact people who need to drive to doctors, Hidalgo said he looks forward to the positive impacts for drivers like him. “Every single time we think about the doctor's appointment or the care that we need to take (our son) to, we have to factor in for congestion – and an absurd amount of congestion,” he said. Hidalgo said he and his wife have had some emergency trips for their son too, but they have luckily mostly been at night when there is less traffic. “When people need urgent medical care, they should be able to get there, and they should not be stuck behind people who should be taking mass transit,” he said.

Back on the West Side, Brodhim said he hoped that he and his friends would be the first and only people to get in a car explicitly to pay the toll. After all, the program isn’t meant to increase traffic in order to gain money, even if it has a statutory requirement to raise funds for the MTA. “This is completely counterproductive to the entire idea of congestion pricing,” he admitted. “But I was like, for the first minute, we can be really symbolic and lovely.”

After successfully getting tolled, the group of friends broke out bottles of sparkling wine and apple juice to toast to congestion pricing. One handed Brodhim a quarter for their share of the $2.25 toll. “It’ll get there,” Decaudin quipped. “It adds up.”

NEXT STORY: This week’s biggest Winners & Losers