Interviews & Profiles

Errol Louis is at the heart of New York City politics

The NY1 political anchor and host of “Inside City Hall” balances interviewing elected officials with teaching the next generation of reporters – and launching a new national show.

NY1 anchor Errol Louis has become a household name among New Yorkers interested in politics. Amy Lombard

Errol Louis is used to people coming up to him on the streets of New York. What happened a few weeks ago, though, was unusual.

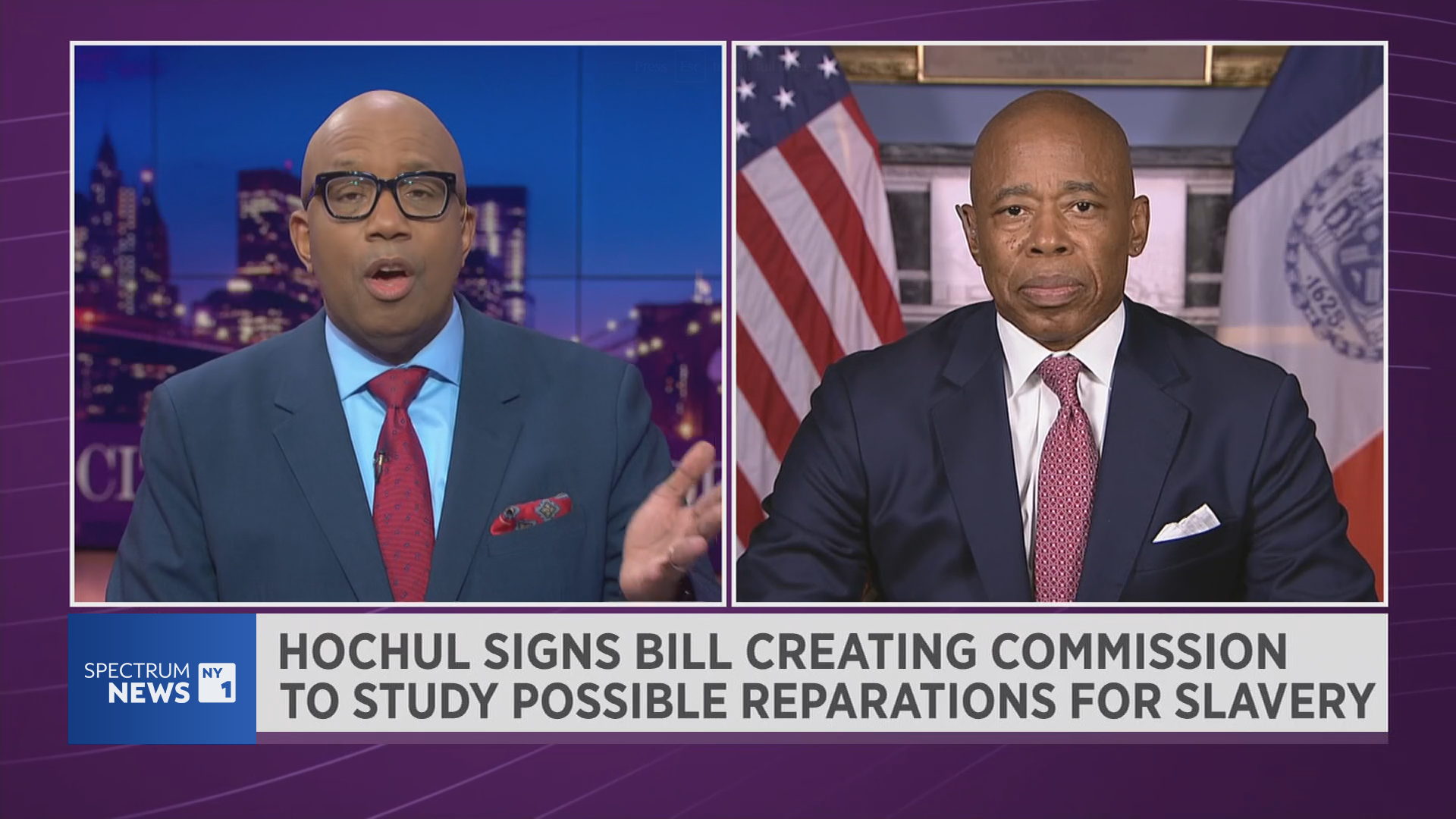

Louis was standing on the corner of West 41st Street and Eighth Avenue, posing for pictures being taken by a professional photographer for City & State. A young man crossing the street noticed the scene and pulled out his phone. He was pretty sure that he recognized the sharply dressed, bald Black man in his early 60s being photographed.

“Mayor Adams!” he called out. “Mayor Adams! Mayor Adams!”

That was only the second time that Louis said he had been mistaken for New York City Mayor Eric Adams; the first was in Washington, D.C., shortly after the mayor had been elected.

Louis is certainly less well-known than the mayor, but among New York politicos and fans of local TV news, he’s the face of New York political journalism.

The longtime political columnist and host of “Inside City Hall” on Spectrum News NY1 told City & State that it’s a rare day when nobody says hello. “You’re sitting in somebody’s living room every night for like 12 years,” he said. “It starts to sink in after a while.”

Increasingly, his influence is being felt outside New York City. Earlier this year, he began hosting “The Big Deal,” a national politics show that airs on both NY1 and its sister stations across the country. He’s also been a political analyst on CNN for the past 16 years.

Louis has never worked as a political staffer or held elected office. That’s not for lack of trying. In 1997, he unsuccessfully ran for a New York City Council seat, and he made a halfhearted attempt to run again in 2001 before ultimately dropping out.

In his various media roles, Louis has become one of the best-known political commentators in New York politics. As an adjunct journalism professor at the City University of New York, he helps train the next generation of city reporters and political journalists.

For Louis, journalism and politics have always been parallel tracks. He began writing columns as an undergraduate student at Harvard University.

“I’ve been a columnist since I was a teenager,” he said. “I was doing it in college. That’s the part that honestly doesn’t feel like work. When my wife says, ‘When are you going to retire?’ and I’m like, ‘Retire from what?’ I know I could do it for free because I did do it for free.”

After graduating from college, and receiving a master’s degree in political science from Yale University, he moved to Crown Heights, Brooklyn. He wrote a weekly column for The City Sun, a local Black newspaper, and did some freelance reporting. But journalism was not yet his full-time job, and he was also closely connected to local politics and community organizing. In 1993, he co-founded the Central Brooklyn Federal Credit Union in Bedford-Stuyvesant with community activist Mark Winston Griffith, and was dubbed a “hip-hop banker.”

In 1997, he ran for the City Council. Term limits for City Council members had only recently been instituted, and it was fairly common for council members to have served for decades – or to have other jobs on the side.

“At the time that I was running, City Council was considered a part-time job, officially,” he said. “So there were people who were running law practices or running a nonprofit, and also serving in the council. My plan was to continue writing, continue teaching and serving in the City Council.”

Louis hoped to unseat Mary Pinkett, the first Black woman elected to the City Council, who had been in office since 1974. He received endorsements from The New York Times editorial board and an array of elected officials, including the powerful Rep. Major Owens. But Pinkett won the Democratic primary with 53% of the vote. Louis came in a distant second, with 28%, while a third candidate, former NYPD Officer James Davis, received 19%. Louis then ran in the general election as the Green Party nominee and did even worse, with 9% of the vote to Pinkett’s 60% and Davis’ 27%.

Pinkett was finally term-limited out in 2001, and the seat opened up. Louis initially declared his candidacy, but dropped out before the primary.

Although Louis never won elected office, he was part of a political generation that has since ascended to some of the highest levels of political power. New York City Mayor Eric Adams, state Attorney General Letitia James and House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries all belonged to the same Black Brooklyn political scene as Louis.

With his nascent political career over, Louis hedged his bets, attending law school while taking a full-time job in journalism.

In 2002, Louis was hired as an associate editor by the New York Sun, a newly launched conservative local newspaper. Although it wasn’t an ideological fit, he said that he enjoyed writing in the Sun’s voice. His work for the Sun won him a commentary award from the New York Association of Black Journalists and notice from the New York Daily News, which hired him as a columnist in 2004.

As a columnist, Louis occupies a privileged position within journalism. He is not subject to the strictures of objectivity and nonpartisanship often imposed upon political reporters, but his work is still held to the same standards of accuracy and ethics. His columns are not just pure opinion; they’re a product of reporting – going out and talking to people, calling up sources – and his own political analysis.

“Errol has been on the scene, in fact many scenes, steadily over the hours, days, weeks, years, decades it takes to have his own perspective – and perspective on the limits of his perspective – and credibly share that,” said Harry Siegel, an editor and columnist who worked with Louis at both the Sun and the Daily News. “That’s something that accumulates values over time, and means he has a deep stock of his own memories and observations to use as new things and characters come up.”

Louis generally avoids explicit advocacy in his columns, but he’s relatively open about his political worldview, even if the exact details can sometimes be difficult to pin down.

“Thank God, I don’t have to take positions on anything. And I won’t. I mean, to the extent that I’m asked to provide analysis or commentary, I do it the way a broadcaster should, which is do it in a way that’s provocative and surfaces ideas and gives everybody a fair hearing and things like that. But it is enormously liberating, to not have to, quote-unquote, win any particular fight. Or election, frankly.”

Still, he’s fairly open about his political worldview. Had he won a City Council seat back in 1997, he thinks he would have ended up as a left-liberal politician – think Working Families Party, not Democratic Socialists of America.

“Somewhere between Jumaane Williams and Brad Lander is probably where I would have landed,” he said. “Basically progressive, not outlandishly so. You know, I believe in private property.”

He’s generally skeptical of progressive insurgents.

His take on DSA: “The DSA folks like to throw around the word socialism. I got a whole shelf of books on it. I did way too much reading about socialism when I was in graduate school. And my question is always, like, where’s the socialism?”

The group’s current focus on contesting Democratic primaries, he said, makes them seem more like a political club than an organization dedicated to building alternative socialist institutions.

Speaking of political clubs, he is not a fan of the New Kings Democrats, the reform club that has been battling the leadership of the Brooklyn Democratic Party for well over a decade. “This is definitely an instance where yesterday’s reformer is tomorrow’s hack,” he said. “I look at these folks, and I’m like, I don’t see somebody who’s a reformer to the core of their bones. I see some people who want power, and that’s fine. Yeah, but let’s call it what it is. It’s a power struggle.”

Louis certainly disagrees with the anti-police rhetoric that some on the left espouse. His father was a longtime member of the New York City Police Department who ran the 73rd Precinct in Brownsville. But he’s not a “Thin Blue Line” ideologue who believes that the NYPD can do no wrong, either. For his family, he said, an NYPD career was mostly seen as a good civil service job that could provide a ticket to a stable middle-class life. He’s skeptical of the fear-mongering around bail reform, and he doesn’t believe that the police should be involved in responding to mental health distress calls.

He has been particularly critical of the NYPD’s internal politics and the way that the department’s current top brass have been attacking their critics – including Siegel, his former editor – online.

In a statement to City & State, the mayor stopped short of praising Louis but emphasized the importance of journalism and hearing different perspectives.

“Journalism plays an integral role in ensuring all voices are heard, and Errol has been an important part of that conversation for decades,” Adams said in a statement. “I’ve known Errol for a long time, and while we may not agree on every issue, I am sure we both agree it is important to have many voices across our city.”

In the NY1 studio inside Chelsea Market, there’s a visual joke that illustrates the channel’s focus: five clocks showing the current time in each of New York City’s five boroughs. It’s a nod to classic broadcast news programs whose sets included clocks displaying what time it was in different major cities around the world, but all five NY1 clocks are set to the same time. The point is that NY1 is dedicated exclusively to covering the five boroughs.

“In NY1, we focus our newscasts and our newsgathering and our whole editorial operation is based on the five boroughs … we don’t cover the tri-state, we cover New York City,” said Sam Singal, Spectrum News’ Group vice president of editorial.

The channel occupies a special place within the lives of many New Yorkers. When Louis was hired as political anchor and host of “Inside City Hall” in 2010, he became a household name. Like his NY1 colleague Pat Kiernan, he has even made cameos in TV shows playing himself.

As the host of “Inside City Hall,” Louis helps set the agenda for political debates within New York City. The bulk of the show consists of probing but largely friendly interviews with elected officials and other political players, which gives them the chance to explain themselves. He also hosts a weekly segment, “Reporters’ Roundtable,” which features local political reporters – including City & State journalists – discussing their work. It all makes for much less riveting television than the bombastic interviews often seen on national cable news channels, but the show does a better job informing viewers.

“Stress testing politicians and the policies they’re proposing and their arguments is really important,” said Siegel, who has appeared on “Inside City Hall” a number of times. “It’s not an impossible threshold and people can judge the performances for themselves, but putting public figures through those motions is important. It’s basic hygienic stuff, the toothbrushing of journalism, and it really matters. It’s not ultra-glamorous, but if you don’t do it, things rot.”

Siegel said Louis knows how to strike the right balance between allowing an interview subject to say their piece and challenging their arguments, and it provides a service to his viewers. “Taking someone through a structured conversation that is not utterly contentious but is challenging is helpful and lets people judge for themselves who can or can’t respond to that and how well they do,” he said.

NY1 is part of a larger network of hyperlocal channels spanning the country, with stations in 11 other states: California, Florida, Hawaii, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Missouri, North Carolina, Ohio, Texas and Wisconsin.

“Although we’re the first and we’re the biggest and we’re the flagship, there’s a lot of interesting stuff going on on our sister channels,” Louis said.

It’s that insight that led to the creation of Louis’ new show, “The Big Deal.” Singal, the Spectrum News executive who helped create the show, said the goal was to cover issues that affect national politics from the perspective of local reporters who intimately know their communities.

“We look at it through the eyes of all of our political anchors and reporters and analysts around the country,” he said. “Because regardless of the story, regardless of the issue, it’s each community. And one of the things this program allows us to do is to tap into our local political experts around the country.”

“The Big Deal” is not the first time that Louis is weighing in on national politics, but it’s the first time that he’s hosting his own show focused on political issues outside of New York.

“My own private working title (for the show) was, I would call it the swing state report,” he said. “The election is going to come down to seven swing states, and we’re in five of them.”

On a recent Thursday morning, Louis sat in a classroom at CUNY's Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism as he waited for journalism students to arrive. “I never took a journalism class,” he said. “So this, for me, is a way of trying to give in condensed form what I wish somebody had told me a long, long time ago.”

Since 2011, Louis has co-taught “Covering City Government and Politics,” a second-semester course that teaches students about the key institutions and players in city politics, along with the best techniques for reporting on local politics.

The class is part of the school’s Local Accountability Reporting program, formerly known as the Urban Reporting program. Jere Hester, the former editor-in-chief of local news outlet The City and the current head of the program, said Louis is a great teacher, both in terms of his rapport with the students and his nearly unparalleled knowledge of local government and politics. “They’re very lucky to have the guidance of somebody who’s not only a practitioner but one of the best in the game,” he said. “I tell students before they take this class that they’re going to be taking it with somebody who knows more about how the city runs than the mayor does.”

During a recent class, Louis began by discussing the controversy over a recent column by Siegel that was critical of the NYPD. He explained that Siegel had made a minor error in his column – reporting that there had been 10 homicides on the subway between January and March when the actual number was four – and that NYPD brass had taken advantage of the quickly corrected mistake to accuse Siegel of being anti-cop.

“If people are waiting to attack you, you don’t have to help them,” Louis told the class. “You don’t want to give them any ammunition. … You’ve got to get used to the idea that, No. 1, even seemingly minor errors can really blow up. You’ve got to be responsible for every word and number that has your name on it.”

After discussing Siegel’s column, Louis spent some time answering questions from students about their class projects. One student said that when they reached out to a City Council member’s office for an interview, the communications director asked them to send over the interview topics or questions in advance. The student wanted to know whether this was ethical.

Journalism students are generally taught that sending questions in advance is verboten, but Louis – as a working political journalist – recognized that in practice, the question is much more nuanced. “Is it a hostile interview?” he asked the student. When the student said he did not expect it would be, Louis said that it’s not unreasonable to send over topics in advance so the council member can prepare for the interview, though there was no need to send over the actual questions. He also reminded students that even when a journalist does send over questions in advance, there’s nothing stopping them from asking unapproved questions once they’re actually in the room with an interview subject.

He went on to give the class a quick primer on American labor law and the role that unions play in city politics and conducted a remote interview with 32BJ SEIU deputy communications director Rush Perez. He also advised students to try to cultivate 32BJ SEIU members as sources. “They’re unbelievably good sources,” he said. “Doormen – they see everything that goes on in the city. Security guards, same.”

Louis is proud of his teaching, though he disagrees that he’s educating the “next generation” of journalists. “Dude, it’s this generation,” he said. “We are all so shorthanded that these folks are needed like right now.”

He said the CUNY program has figured out a strong regimen for training professional journalists. It starts in the first semester with a class about the craft of journalism. “That’s boot camp,” he said, which teaches the basics of reporting to people with no journalism experience. In the second semester, there’s more specialization – that’s when students take his class. Over the summer, students are required to do an internship in a professional newsroom, giving them real-world experience.

“It’s really wild, but they come back in the fall, and they are, like, a lot better. All of the stuff that has been thrown at them sort of comes together. And they start the process, the last stage of the process, which is going from being students to becoming our peers,” he said.

Louis is serious about seeing his students as soon-to-be peers. He said he doesn’t consider himself a mentor, but rather a “sponsor” – a more mutual relationship between people who vouch for each other’s abilities. “What I tell them, only half-jokingly, is, look, someday when you’re running a newsroom, and there’s some old guy who wants to write a column for you, just remember your old pal!”

Correction: This article has been updated to clarify that CUNY’s Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism is not part of the CUNY Graduate Center.

NEXT STORY: Inner Circle show is jokingly Eric Adams’ ‘inner circle of hell’