Albany Agenda

Jeffrion Aubry, voice of the Assembly, is leaving it after 30 years

The speaker pro tempore was instrumental in repealing the Rockefeller drug laws and building a performing arts center to honor Louis Armstrong.

Assembly Member Jeffrion Aubry visits the Louis Armstrong Center he helped to bring to fruition. Guerin Blask

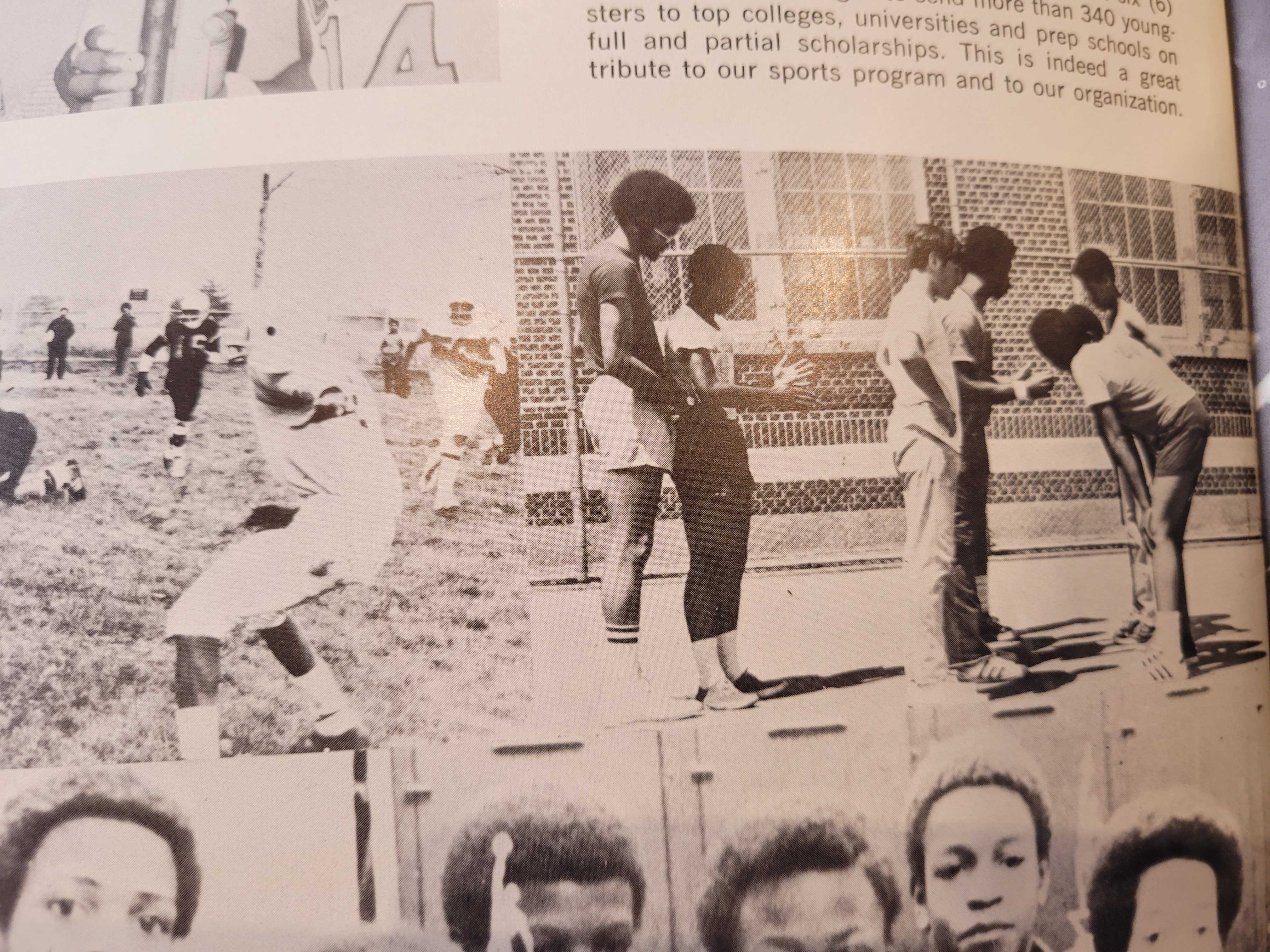

Sitting in the lobby of the Louis Armstrong Center in Corona, Queens, in mid-February, Assembly Member Jeffrion Aubry looked for himself in a yellowed magazine. “I know how old that is – 1972,” Aubry, 76, said of the program. “The long guy with the big big afro,” he said, pointing to himself in a photo. “Things have changed.” The magazine was an old program for Elmcor Youth and Adult Activity, Inc., the oldest Black-led human services nonprofit in Queens. Elmcor remains one of the largest nonprofits delivering services in the area and has produced multiple elected officials, including Aubry’s direct predecessor and potentially his successor. At the time the picture was taken, Aubry ran the education program at Elmcor, and he said it showed him with some of the first teachers and students. When he got his start at the organization, he didn’t see himself going into politics. “We were really kind of on the – how can I say – anti-establishment process,” Aubry said. Elmcor had a lot of ex-Black Panthers back in the day, both as volunteers and as clients. “The question is, do you stand outside and scream, or do you go inside and make it better?” Aubry said. “Obviously, screaming from the outside can help sometimes, but you also have to have people inside who can translate that noise into progressive policies.”

The program was printed to accompany the first Louis Armstrong Memorial Concert that Elmcor helped to organize. For decades, Elmcor had dedicated itself to preserving the jazz legend’s legacy with an educational and performing arts center – and Aubry, through his work at Elmcor, was part of that charge almost since the beginning. He had even worked directly with Armstrong’s widow Lucille over a decade before he entered the Assembly. “I don’t want to talk about it,” he joked about just how long he has advocated for the center, which finally opened last year.

Like Aubry said, a lot has changed in the over five decades since that photo was taken. Although he started on the Louis Armstrong Center project as a young man working for a local nonprofit, he saw its completion as a 30-year veteran of the Assembly, representing the 35th District and his home in East Elmhurst and Corona. In the time between the photo and the center’s grand opening, that “long guy” had made quite a name for himself in the halls of power in Albany. “If you’re talking about government, he is the statesman’s statesman,” said Queens District Attorney Melinda Katz. At the end of this session, that statesman will retire.

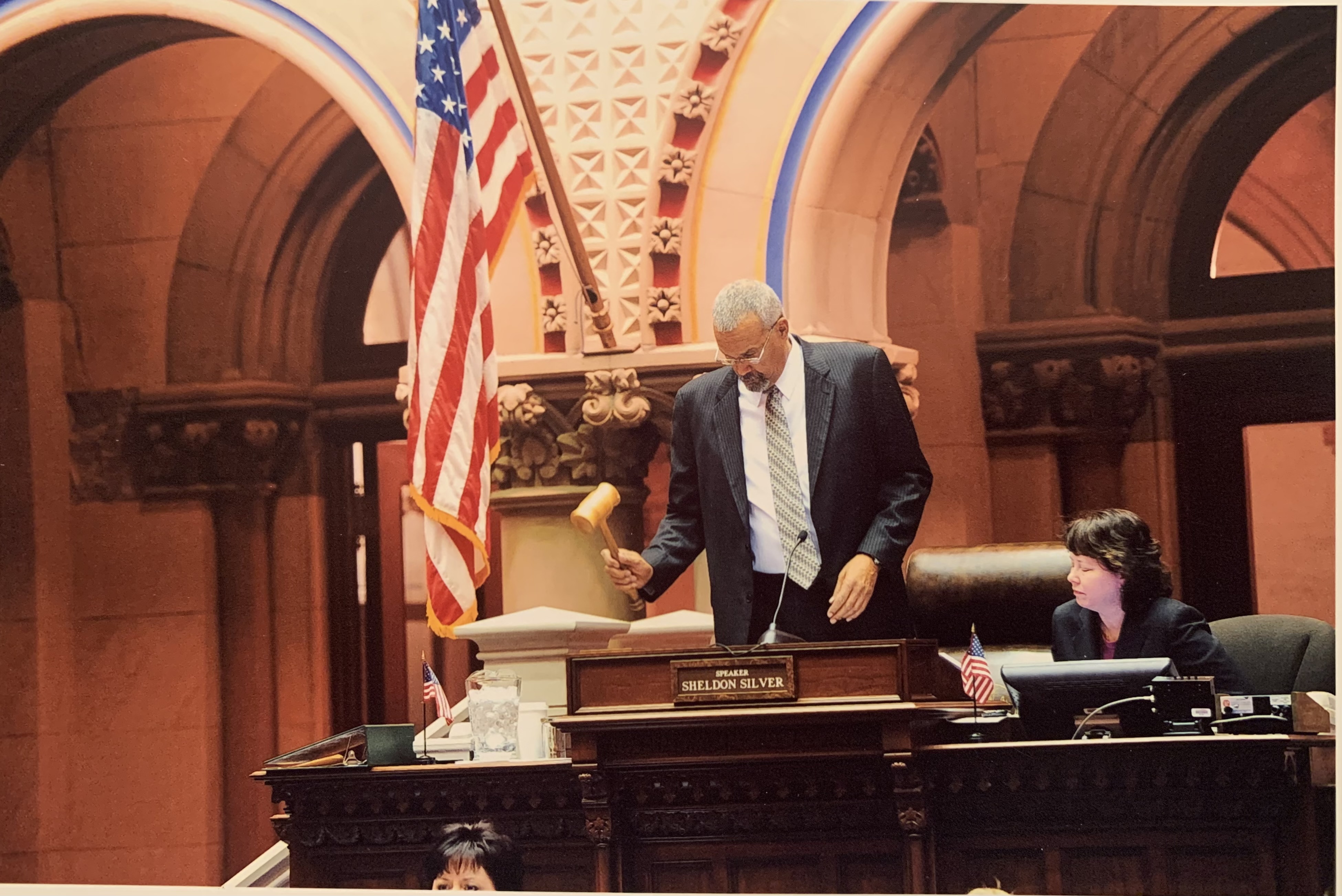

For the past 11 years, Aubry has served as the literal voice of his chamber as speaker pro tempore, presiding over the Assembly every day it meets for session and helping to guide floor proceedings and debate. Administrative phrases inviting members to speak “on the bill” and inquiring “Are there any other votes?” before directing the clerk to “read the results,” have become totally associated with him. “His delivery is so dramatic and cool,” said Brooklyn Assembly Member Emily Gallagher, who said her whole team is feeling wistful about the loss of that voice. “Other people can have a lovely voice, but they don't necessarily carry the drama.”

Aubry’s legacy will also be that of the lawmaker who led the charge to roll back the draconian Rockefeller drug laws in the early 2000s after years of advocacy. “He is a role model,” said Stanley Richards, president and CEO of the reentry services nonprofit the Fortune Society. “His name will ring very loudly in the statehouse and the halls of city and state and federal legislators because he really is a giant in this space.” And Richards isn’t just saying that because Aubry physically towers over people, standing at 6 feet, 7 inches.

Drop the Rock

Aubry’s family migrated from his birthplace of New Orleans to northwest Queens when he was very young. They were one of many Black families who moved from the south in the era of Jim Crow and settled in East Elmhurst and Corona, which at the time of Aubry’s arrival were largely Irish and Italian neighborhoods. The demographics shifted during the ’40s and ’50s as more Black families moved in, much like how the area has welcomed many new immigrants from Latin America over the past few decades.

Growing up in Corona, Aubry often spent summers with his grandmother in New Orleans and Mobile, Alabama. Unlike New York, those cities were still segregated throughout his childhood. His trips down South were always interrupted at the Washington D.C. stop, where trains became segregated. Although he and other Black riders could have taken any seat they wanted when they boarded in New York, they needed to move to the back once they got below the Mason-Dixon line. “The revolutionary part of your life is shaped early,” Aubry said. “So when folks couldn’t explain why that existed to you as a teenager, you kind of get ready to understand that there’s a battle that you’re going to fight.”

Before he got elected to office, Aubry started working for Elmcor largely by chance in the early ’70s, starting with a volunteer group that became the organization’s full-fledged drug treatment program. He became more and more civically engaged, including with his local community board and through his work opening the Louis Armstrong Center. He would go on to become the executive director of Elmcor and eventually run for office. In 1992, Aubry won a special election to replace the late Helen Marshall, who had left the Assembly to become Queens borough president. Marshall, who also served in the City Council, worked for him at Elmcor before she decided to enter elected office. By the time Marshall approached him to run for her seat in the Assembly, Aubry had gone on to work for the Queens borough president and was ready to make the jump into political office himself.

Five years after taking office, Aubry introduced for the first time legislation to repeal the harsh drug laws imposed by former Gov. Nelson Rockefeller. Those laws, enacted in 1973, were among the most restrictive in the nation, a harshly punitive response to public fear about drug abuse. The rules implemented lengthy mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug offenses, which caused prison populations to skyrocket and disproportionately impacted communities of color hard hit by the crack epidemic of the ’80s and ’90s.

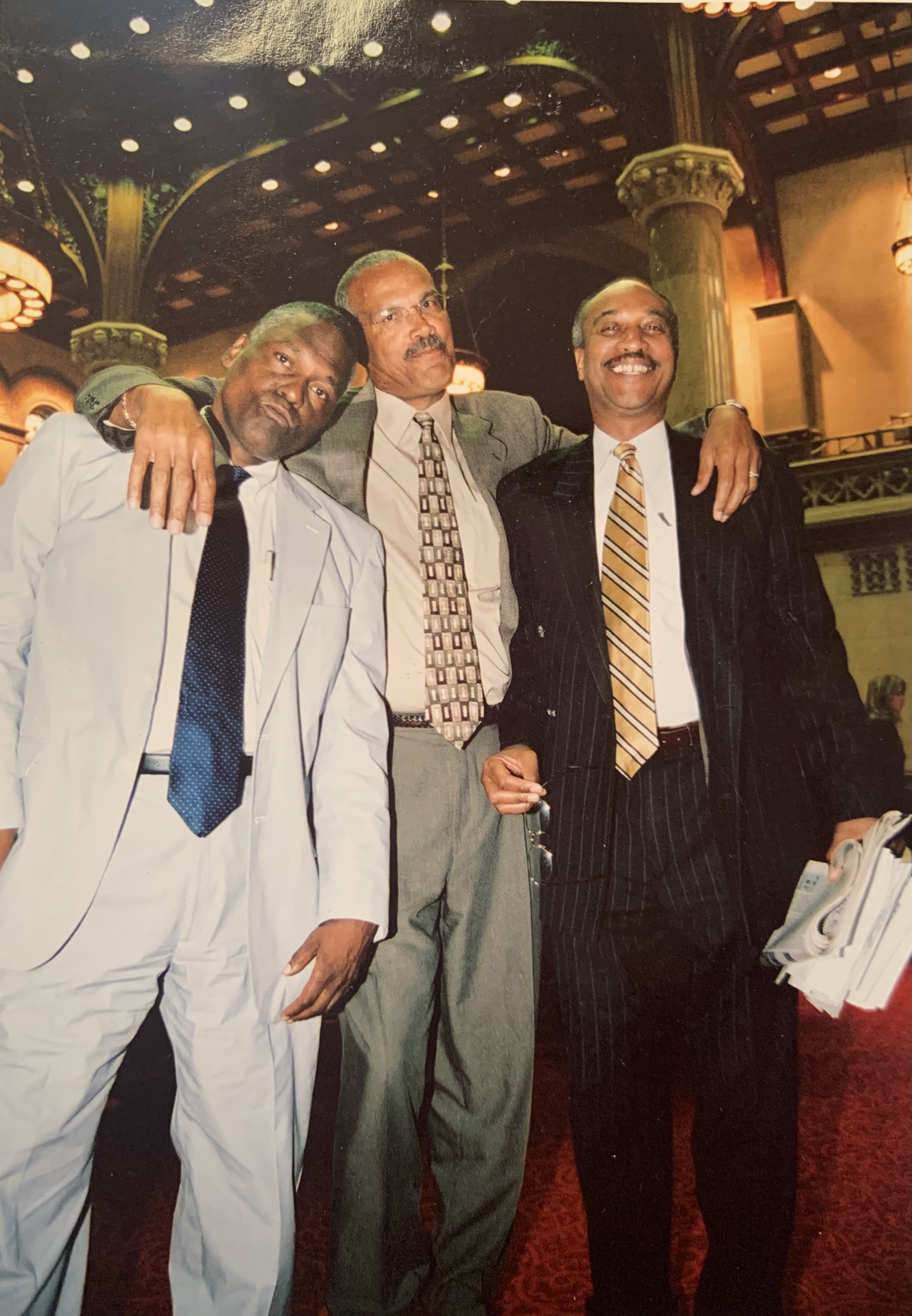

“It wasn’t easy,” said former Assembly Member Keith Wright, a friend of Aubry’s who took office about the same time. “He did it when it wasn’t popular to do so, so I don’t think anybody else would have done it,” Wright said. It took 12 years between when Aubry first introduced legislation in 1997 before his fight came to an end with then-Gov. David Paterson’s signature in 2009. That bill signing took place at Elmcor, where then-Speaker Sheldon Silver recognized Aubry’s advocacy that started at the organization.

Those who know and have worked with Aubry describe him as a rare legislator uniquely committed to his ideals, especially in the realm of criminal justice reform. “He came in with a level of integrity and a moral compass that he never lost,” said Dr. Divine Pryor, a longtime criminal justice advocate who is currently CEO of the People’s Police Academy at Medgar Evers College. He first met Aubry in the early ’90s not long after his release from prison, when Pryor was first starting his own activism. “One of the things that I like about him is that he went out and talked directly to the people who were impacted,” Pryor said.

Gabriel Sayegh, who co-founded the Katal Center for Equity, Health and Justice and in the early 2000s, helped coordinate the Real Reform NY Coalition to repeal the Rockefeller drug laws, recalled a defining moment for him came during a 2004 trip to Albany. It was one of the first advocacy trips to the state capital he had organized, with a bus full of Brooklyn church members who were meant to meet with then-Majority Leader Joe Bruno. The Republican leader canceled at the last minute, but Sayegh said Aubry rearranged his schedule to meet with the group instead when he learned about what happened. “These are folks that had never been to Albany before, and they left as committed advocates,” Sayegh said. “That’s just kind of how he was … If you showed up and needed support on the day, he’d try to find it for you.”

Later in his tenure, Aubry continued to lead on criminal justice issues as the sponsor of the HALT Solitary Confinement Act to end the use of punitive isolation in state prisons. A broad coalition pushed for the legislation, which became law in 2021. “Having him at the forefront of reducing the use of solitary in our New York state prisons as a woman who experienced solitary, and to have him hear my story and almost come to tears. And to have him take that back to his colleagues and say, ‘We have to do something about this,’” said Anisah Sabur, a criminal justice activist who was part of the HALT coalition who continues to fight against the use of solitary confinement. “That’s why I said there can’t be another champion for me.”

Even behind closed doors, Assembly members who served with Aubry said that his convictions never wavered on issues of criminal justice and ending mass incarceration. Former Assembly Member Richard Gottfried, who retired last year after more than four decades in the chamber, said Aubry would often oppose legislation that would increase penalties for certain crimes, like assaulting a train conductor or bus driver. Gottfried said those bills usually moved through with little fanfare – with the exception of Aubry. “There was always one voice that would stand up in the Democratic conference and just as a matter of principle speak against the elevated penalties,” he said. “I was just always impressed with (Aubry’s) real commitment to that principle and being usually the lone voice standing up and speaking out.”

Man in the mural

Until relatively recently, one could have found Aubry’s face in a mural in LeFrak City, the largest housing development in the district. The mural served as a hall of fame of sorts among residents, honoring famous alumni that came out of LeFrak, like basketball player Kenny Anderson. But that mural was recently painted over. “The owners don't have any ties to the community,” said Martha Ayon, a Democratic consultant who grew up in Aubry’s district and around LeFrak City. Growing up, Ayon wasn’t politically active, but she knew Aubry. “For us in the district, he's always that figure that always thought about the kids and the seniors,” she said. Even though it’s gone, Ayon said Aubry “has every right” to be next to other LeFrak hall-of-famers the mural once featured.

Juliane Williams became the president of the LeFrak City Tenants’ Association a little over a year ago. Although she is relatively new to the role, Williams had already known Aubry from the support he offered in the wake of her daughter’s traffic death in 2016. “He was always there with me, standing with (former state Sen. Jose) Peralta … speaking to me after, comforting me,” Williams said. She said she trusts Aubry thanks to their existing relationship, and added that his word carries weight among other longtime residents in LeFrak as well.

Other current leaders in Corona and East Elmhurst have known Aubry their whole lives, including state Sen. Jessica Ramos, his partner in the upper chamber. She was in her mid-20s when Aubry succeeded in repealing the Rockefeller drug laws, just starting her own career in civics. “He’s really been a tremendous inspiration for me because in that endeavor, he proved to me that, you know, a kid from this neighborhood, could actually make change happen where it matters most,” Ramos said.

Many of the over two dozen people that spoke about Aubry for this story described him as a mentor. Elmcor’s current executive director Saeeda Lesley Dunston has known Aubry for basically her whole life, having attended school and played basketball with his daughter. She described Aubry as always present when she needed help even if they didn’t speak regularly in her adulthood.

That included the sudden death of her sister in 2013. “At the funeral, once again on cue, he was just there,” Dunston said, despite them not speaking beforehand. “And he doesn’t say much, he doesn’t have to, he just needs to be present.” A year later, she took the job with Elmcor. “Jeff was one of the people who had said to me, ‘You need to give to your community all the things it gave to you,’” Dunston said.

Now, Aubry has endorsed another Elmcor alum to replace him. Larinda Hooks, who serves as the vice president of older adult services, said Aubry first convinced her to run for district leader four years ago after she initially turned him down a few times. “I know that he’s a big, big fan just of my advocacy for the community,” Hooks said. She said Aubry, whom she has referred to as a godfather, approached her when he made the decision to retire to ask if she was ready to run for his seat. “It was kind of a jolt, a shock,” Hooks said. “But I was like, in my head, who better than me? So yes, I’m ready.”

Casino controversy

As Aubry winds down his time in office, one of the last acts he hopes to accomplish is also an instance where he has faced relatively rare criticism: opening a casino next to Citi Field. Aubry introduced legislation – to the surprise of many including Ramos – that would pave the way for Mets owner Steve Cohen to build a casino in the Citi Field parking lot, which is technically state-owned parkland.

The prospect of opening a casino in the space has sparked some intense backlash particularly in the area of Flushing, which the casino would directly impact. Aubry does not represent Flushing, but Citi Field falls within his district lines. Those advocates against the casino expressed disappointment in Aubry’s decision to back Cohen’s development plan. “What the Assembly member is trying to do is hand off a huge chunk of land, which is public, it’s parkland – that means it belongs to the entire community – to a billionaire,” said Sarah Ahn of the Flushing Workers Center, a group that’s part of a coalition fighting the casino.

Ahn attended a protest last May outside of Aubry’s office to express displeasure with his position. She said that while he was respectful and heard them out, he also didn’t truly listen. “I also think his mind was made up and there wasn’t any – there wasn’t any open dialogue of, ‘Let me hear what people’s concerns are,’” Ahn said. She added the brief interaction contrasted with how Ramos, one of the other key voices in the casino debate, has engaged with the issues. The state senator, who has not taken a position yet, has held numerous public town halls to hear from what residents thought about the prospect. Ramos said that she invited Aubry to the first one, but he didn’t attend.

Aubry said he sees the casino as a major economic opportunity for his district and downplayed the amount of opposition that exists. “I don’t think in the 35th, and what I know of the people in my community, are really split on the casino. I think there’s a fair majority (in support).” Aubry said. “If I’m doing what my community has told me to do, then I’m supporting the bill and I’m putting the bill up.” Elmcor is one of the local groups that supports developing the casino, although Williams of LeFrak City said she has reservations about neighborhood benefits and wants to speak about it further with Aubry before he leaves office.

Aubry also supported former Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s controversial and ill-fated AirTrain project. That was one of the major campaign targets of former New York City Council Member and former state Sen. Hiram Monserrate, who is a district leader in Aubry’s district, and has run against Aubry twice. After challenging Aubry in 2020 and 2022, Monserrate is now seeking to replace Aubry once he retires. Monserrate took pains not to disparage Aubry or his impact on the East Elmhurst and Corona neighborhoods, but called him a Party insider, at times to the detriment of residents. Monserrate described himself as more independent. “Some would argue that you know, machines make things happen,” he said. “I also understand that machines help a very small, select group of people get very rich, and very powerful. And there's no progress here at the local level.”

The state Senate expelled Monserrate in 2010 following a misdemeanor assault conviction in a domestic violence case, and he has been attempting to make a political comeback ever since, running not just for Aubry’s seat, but also for the 39th Assembly District and twice for City Council, and succeeding in his 2018 district leader race. Aubry has largely avoided making personal attacks against the former lawmaker.

Monserrate also pointed out demographic changes in the district – the once majority Black area now is majority Latino. But those changes alone haven’t sold everyone. Ramos, who has already endorsed Hooks, rejected the idea that the demographic shift has impacted Aubry’s representation. “You’re talking to the state senator who represents the most diverse community in the entire country,” Ramos said. “As a Colombian American, I don’t just represent Colombians – I don't even just represent Latinos … To me, the notion somehow that Jeff Aubry has not represented the Latino community, I disagree.”

But where Aubry was one of the first Black officials to represent Northwest Queens along with his predecessor Marshall, he is now also among the last. “He's part of this legacy that kind of like moved on, died off,” Ayon said. “That’s reflective of a lot of parts of the city … Hopefully people will remember his contributions, because he did a lot.”

Conscience of the conference

Those who know Aubry describe him as one who doesn’t seek the spotlight and who chooses his words with care. It’s somewhat ironic, then, that anyone tuning into the Assembly session will hear his voice, moderating floor debates and presiding over the daily activities. “People say it’s the voice,” Aubry said. “I guess I have kind of a placid demeanor.” He said he didn’t campaign for the position before former speaker Sheldon Silver appointed him in 2013, but he felt he had reached a point in his career where it made sense for him to take on the new role.

Aubry’s voice has become iconic among plugged-in politicos and his colleagues alike. That’s both in the soothing yet commanding way in which he speaks, and in what hearing his voice represents. “He is always a voice of reason,” said Assembly Member Chantel Jackson of the Bronx. “So when we have a conference, or we're having specific committee meetings, his voice is always the one that everyone is quiet for, and listens to attentively, no matter what he's saying.”

During his 30 years in the Assembly, Aubry has gained a tremendous amount of respect from his colleagues that has only grown since he took on his official leadership position over a decade ago. “Jeff has been described as the conscience of the conference, godfather, Uncle Jeff, so he’s been a trusted adviser for me sometimes even when I didn’t know what direction to go in,” said Speaker Carl Heastie.

Assembly Member Michaelle Solages, who chairs the Black, Puerto Rican, Hispanic and Asian Legislative Caucus, called him the “guiding light in everything that we do.” The caucus has grown significantly since Aubry first took office in 1992 and now boasts nearly 80 members. Solages said the insight he brought from years of advocacy for communities of color was invaluable to members as the caucus grew in influence.

Solages specifically remembered an instance from last session when some 25 members were debating budget issues when Aubry’s turn to speak came up. Solages said he expressed happiness at seeing members passionately debate the issues because “we can hold down the fort.” “He felt that we were all in good hands, that we would carry on his legacy,” Solages said. “I think he'll be proud of us because we all had the opportunity to at least be able to be with him and learn from him.” At the time, Solages didn’t know Aubry would announce his retirement within a year.

Other members offered stories of Aubry’s generosity with constituents and desire to connect with the people of the state. Assembly Member Charles Fall said several years ago, Aubry asked if he had disabled residents in his district and offered to connect Fall with a nonprofit that provides free motorized chairs. In the end, five of his constituents benefited from that. Aubry followed up to see how things worked out, but Fall said he never made it about himself. “He doesn’t even look for the credit, and I think that speaks volumes on who is as a public servant,” Fall said.

Assembly Member Ron Kim, who called him “the epitome of the modern-day statesman,” said he remembered how Aubry chose to sit with Kim’s constituents at his first inauguration rather than stand with other elected officials in the front. “Despite his status, Jeff wants to stand with the crowd and not the podium,” Kim said in a text. “While most politicians sought the spotlight, he found joy in sitting and connecting with the people who sent us to Albany.” Part of Aubry’s job as speaker pro tempore is to welcome guests into the chamber, the endless enthusiasm for greeting each and every visiting group impressed Gottfried as well. “I think people who are greeted by him must come away feeling really special, and that’s just a lovely thing that he does,” Gottfried said. “And no matter no matter how many times he does it, it’s always fresh and sparkling and sincere.”

Correction: This story originally misstated Stanley Richards’ title. He is president and CEO of Fortune Society. It also originally misstated the campaign that Gabriel Sayegh helped to coordinate. It was the Real Reform NY Coalition.

NEXT STORY: This week’s biggest Winners & Losers