Proponents of congestion pricing have their hearts in the right place. They want a dedicated revenue stream for New York City’s crumbling public transit infrastructure while simultaneously reducing traffic congestion and, subsequently, pollution.

But in order for the plan to be truly effective in reducing the number of cars on the road, it should focus less on Manhattan and more on easing gridlock in the outer boroughs, where traffic is often just as bad – if not worse.

In the past 20 years, New York City has seen a population and business boom unlike any since the mid-1900s. Between 2010 and 2016, the U.S. Census Bureau estimates the city’s population grew 4.4 percent – with the bulk of that growth occurring in the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens, followed by slower growth in Manhattan and Staten Island. In fact, the Bronx is less than 20,000 people from reaching its historical population high set in the 1970 census and could soon surpass Manhattan to become the third-most-populous borough.

Business growth followed a similar, if not more extreme, pattern. Brooklyn saw a 48 percent increase in new businesses between 2000 and 2015, with Queens reporting a 33 percent increase, the Bronx 26 percent and Staten Island 22 percent, according to a report released this spring by New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer. In that same period, the number of Manhattan businesses actually declined 2 percent – and that included Central Harlem, where businesses nearly doubled.

The report also found that most of the growth was in low-income and gentrifying neighborhoods, bringing a new influx of income and vehicles into places like Crown Heights, Williamsburg, Greenpoint and Bedford-Stuyvesant.

RELATED: Could congestion pricing save the subway?

Much of this growth is the result of recent policies enacted during former Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration, such as the rezoning of Fourth Avenue in Brooklyn and the influx of new residential development in areas like Long Island City, Bushwick and Atlantic Yards. Saying nothing of the increase in the volume of drivers and vehicles through initiatives like the addition of green taxis to the outer boroughs and later, under Mayor Bill de Blasio, the legalization of ride-hailing services, whose fleets now outnumber yellow cabs 4-to-1, with many of them driving and residing in the outer boroughs.

Amid such outer-borough growth, Manhattan officials have taken steps to revitalize its neighborhoods, such as rezoning East Midtown and thinking about ways to narrow the commercial rent tax.

“If you look at New York historically, Manhattan’s dominance as an economic center has not been the case,” said Mitchell Moss, a professor of urban policy and planning and director of the New York University Rudin Center for Transportation. “Until the post-World War II era, the vast majority of manufacturing was outside of Manhattan. So I think it’s important to realize we’re seeing a reassertion of the employment centers outside of Manhattan.”

“If you look at New York historically, Manhattan’s dominance as an economic center has not been the case.” – Mitchell Moss, director of the Rudin Center for Transportation

Move NY is one of the leading organizations at the heart of the congestion pricing debate. Using analysis of traffic patterns in New York City, along with input from local leaders, community groups and former New York City traffic commissioner “Gridlock Sam” Schwartz, the group has offered detailed plans for instituting congestion pricing. The Move NY proposal centers on tolling vehicles entering Manhattan below 60th Street, known as the central business district, including the currently free East River bridges and lowering the tolls on several outer borough crossings.

The group’s research on the number of vehicles in New York City supports the notion that the majority of car owners live outside of Manhattan. And while those who own a car in Manhattan have a median household income of $134,000, that number plummets to roughly $80,000 on average for the other four boroughs, or a couple each earning about $40,000 a year – solidly middle class.

The data also indicates that most people who have cars in New York City do not use them to commute into Manhattan, and the great majority of commuters in the boroughs use public transportation. As most people who drive in and around the New York City area will tell you, the traffic is much worse in the areas that connect Brooklyn and Queens (left) with Long Island, and the Bronx with Westchester County, than it is in and around the Manhattan crossings.

And yet, all of these areas – even the fastest growing areas of Manhattan – are outside of the proposed, relatively car-free central business district.

Which begs the question, why is congestion pricing centered on Manhattan?

“We’re not taxing cars or motorists, or charging driving or cars or motorists – we are charging congestion,” says Charles Komanoff, a transportation economist and environmental activist whose research is at the core of the Move NY proposal. “We’re trying to increase tolls on trips that through their timing, and especially their location, end up imposing really large congestion costs on society at large.”

While the number of cars on the road is easy to determine, congestion during different times of the day is tough to quantify. Komanoff has made it his life’s work. His "balanced transportation analyzer” – an Excel spreadsheet that he jokes is so large, “if you were to display all of the tabs simultaneously, you would use up more window space than exists in Manhattan south of 17th Street” – breaks down and monetizes all aspects of New York City transportation. Using the current modes of monetization as the baseline, it estimates the net impact not only of the Move NY plan, but other possible solutions, such as raising subway fares or only tolling the East River bridges.

While the additional revenue is apparent in all of the potential solutions, Komanoff prioritizes time spent commuting as the driving force (pun intended) behind his support for the Move NY plan. And based on his numbers, it does bear fruit, and not just for those who use public transit. Based on his estimates, drivers would enjoy a 22.3 percent increase in average vehicle speed if the plan was enacted. But it’s worth noting his projections are based on the completion of a triborough subway line that connects the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens.

RELATED: Will Cuomo's support get congestion pricing across the finish line

More concerning in the current Move NY proposal is a reduction in tolls on the outer-borough bridges – a policy even congestion pricing supporters admit is a political move to sway suburban and outer-borough politicians.

Komanoff himself said, “It’s good policy, but even more, it’s good politics.” When I pressed him on whether this means more vehicles pushed to the other boroughs, especially if the tolls on the outer-borough bridges are lowered, he was forthright.

“I agree, price elasticity. I’ve got to believe if I’m saying that to raise the price to drive into the CBD is going to lower the amount of car trips into the CBD, I’ve got to believe in the converse or the reverse, sure,” he said.

“But,” he added, “remember we’re taking a certain number of traffic off the streets, before it even gets to the CBD. The net is very clearly a reduction.”

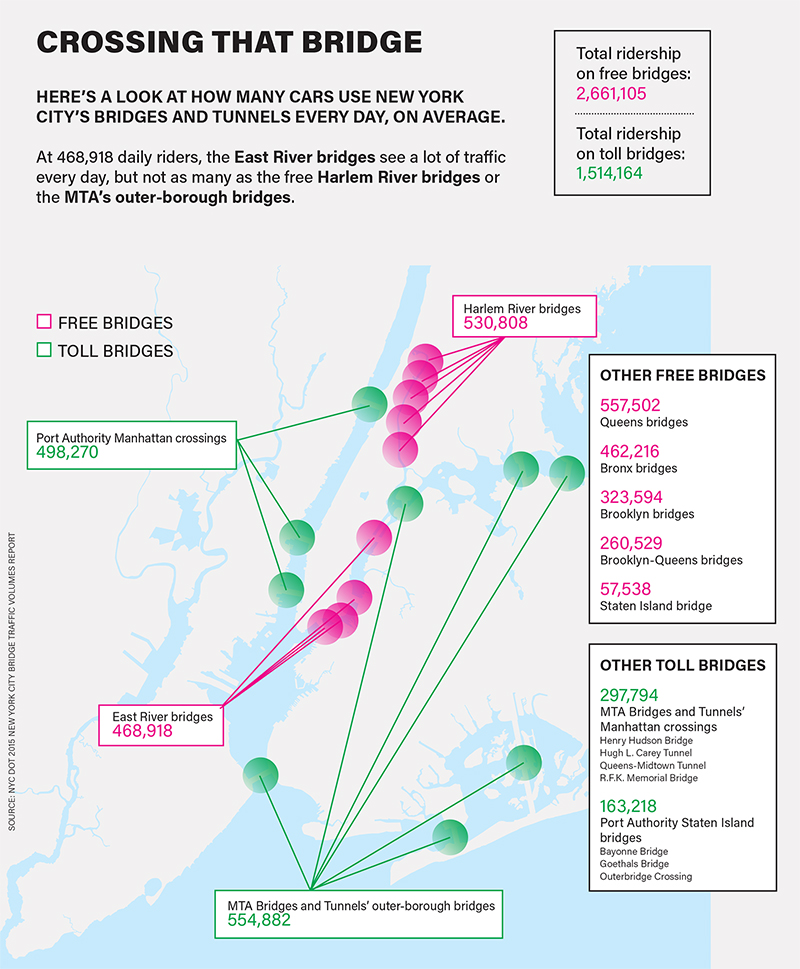

Still, the numbers suggest cars aren’t flowing over the East River bridges at the same clip as the rest of the city. Of the toll-free bridges in New York City in 2015, the East River bridges represented roughly 469,000 daily trips – barely 18 percent of the total daily bridge crossings in New York City. By comparison, more cars traversed the free Harlem River crossings – over 530,000 – to enter Manhattan, but again, those were above the central business district.

In fact, more cars used the tolled outer-borough bridges – nearly 555,000 – and Hudson River crossings – more than 498,000 – than the free East River crossings, and that doesn’t include the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge (formerly the Triborough Bridge), which averaged more than 91,000 paid trips into Manhattan above 60th Street. All of which points to more traffic and congestion outside Manhattan than inside.

“The theory that you would put a surcharge where use is reducing is contrary to most governance,” said Moss, adding that lowering the tolls on the outer-borough bridges is a “high-risk strategy.”

“The genius of the MTA is that we took the tolls from bridges and tunnels and have used them to support mass transit. The reduction of tolls, especially where those bridges have increasing demand, is perhaps politically driven but not fiscally sound,” Moss said. “It makes very little sense to impose a toll to come into Manhattan and then lower the toll for activities that are not tied to New Yorkers.”

(Click to view larger)

It’s also worth noting that the Move NY plan is the second-best option according to Komanoff’s research.

The best solution is the Move NY plan, but with variable tolling below 60th Street in Manhattan – charging more during peak times and less during off-peak hours – rather than a flat toll. And it makes sense. The world is increasingly moving toward incremental payment structures to improve efficiency, such as surge pricing with Uber and Lyft. Multiple states have taken that concept and applied it to variable tolling on highways, often referred to as express toll lanes or high-occupancy toll lanes, to improve efficiency and allow drivers to utilize free or paid lanes.

However, the proposed solutions for turning Manhattan into a car-free utopia don’t begin to address the worst traffic quagmires in the outer boroughs.

There’s nothing dissuading Long Island drivers from driving into Brooklyn and Queens, even if the confluence of the Long Island Expressway, Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, Van Wyck Expressway, Grand Central Parkway and Jackie Robinson Parkway is often viewed as one of the worst traffic areas in the city.

There’s no part of the congestion plan that addresses Harlem River Drive, a clogged artery of daily commuters trying to enter and exit the city. Could it address the line of cars that span Bay Ridge to Red Hook every day on the Gowanus Expressway? Or the traffic that lines the Belt Parkway in Southeast Brooklyn or Queens Boulevard – also known as the Boulevard of Death?

There’s no part of the congestion plan that addresses the Harlem River Drive, the Belt Parkway in Southeast Brooklyn, or Queens Boulevard – also known as the Boulevard of Death.

“The guy or the gal who lives in Bay Ridge, or Scarsdale, or Flushing, who’s now driving into the CBD isn’t just congesting the CBD on that trip, it’s congesting all the streets, roads, highways, approaches and the bridges themselves. That traffic is going to diminish,” Komanoff countered.

“Most of the transit benefits are going to be outside of Manhattan,” he added, pointing out that his projections are based on five years out “when the transit investments have borne fruit.”

Yet even “Gridlock Sam” Schwartz himself jokes about the length of time it takes for the MTA to complete major infrastructure improvements. Idealistic at best, five years seems like an unrealistic goal.

“Some of these benefits aren’t going to be able to be realized over night, and we know that. There’s a little bit of a leap of faith in there,” Komanoff said.

That’s a big leap of faith when you consider there are already more people driving in the outer boroughs, fewer subway lines, more commuter cars crossing the outer-borough bridges than those coming into Manhattan – even more bicycle and pedestrian deaths by vehicles in the outer boroughs.

The data shows that the population and businesses of New York City are shifting away from Manhattan, a trend that shows no signs of slowing down.

And like those forward-thinking businesses, renters and homeowners, a progressive congestion pricing plan should take this reality into account.

If Move NY’s proposal is contingent on the addition of more train and public transportation options in the outer boroughs, then they must factor in what the city’s population will look like when those projects would be completed. Because whether you think congestion pricing is progressive or regressive, it’s still dependent on cars driving into New York City during the busiest hours.

“It’s an ecology,” Moss said. “We need to have people driving to support those bridges and tunnels, which support mass transit. And the subway system isn’t big enough to get everyone out of their car into it. We have to find the balance.”