“Stand up if the answer is yes … Do you plan to use the public advocate position to run for mayor?”

Jumaane Williams slipped off his chair and sat straight-legged on the ground. It drew laughs from the sparse crowd. The New York City councilman wasn’t just going to say no by staying seated – he was going to be extra-seated.

The moderator at a Jan. 31 forum for public advocate candidates at Boys and Girls High School in Bed-Stuy had asked the candidates to simply stand or stay in their chairs, not to sit on the floor or jump up and down. Well, Williams often jokes that his nicknames in school were “needs improvement” and “promotion in doubt.” This was the same class clown, now grown up and running for higher office.

Though Williams may have been more seated than anyone else, none of the candidates stood up to express an interest in running for mayor. And no one stood when, an hour later after four more candidates arrived late, the moderator posed the question again. (Williams slunk to the ground again, to fewer laughs.)

The candidates’ commitment to public advocacy raises a central question of the race: Why should voters care who the next public advocate is? An obvious answer is that, as first in the line of succession if the mayor dies or steps aside, one of them could soon be mayor of New York City, a job with actual responsibilities and an immense budget. And even if tragedy – or a job in Washington – doesn’t befall the sitting mayor, and the public advocate never has to take over, the holder of the office is in prime position to move up in the future. The role was created in part for that exact reason. And it’s worked! Just look at the office’s two previous occupants: New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, and state Attorney General Letitia James, whose November election got us into this mess of an unprecedented citywide special election set for Tuesday, Feb. 26, to fill her vacancy.

They claim they’ll direct recreational marijuana taxes toward fixing the subways, or stop Amazon from expanding into Queens. Of course, the public advocate can do none of that.

And yet the candidates shy away – at least publicly – from that particular ambition of becoming mayor. Day after day, in press conferences and on podcasts, and night after night, in forums and debates, the candidates are seeking to convince potential voters to care about the race for other reasons. They claim they’ll direct recreational marijuana taxes toward fixing the subways, or use eminent domain to seize land and build affordable housing, or stop Amazon from expanding into Queens. Of course, the public advocate can do none of that. Voters may find it nice to have an elected official who agrees with them on certain issues, but the public advocate has limited powers outside of … advocating. But hey, drawing the occasional attention of the New York City press corps can be a powerful thing. And even if the candidates won’t cop to it, the public advocate is just a Bernie Sanders presidential transition team phone call to Gracie Mansion away from becoming mayor of the greatest city on Earth.

That’s partly why the job is so popular. More than 30 candidates threw their hats in the ring initially, and 17 made it on the ballot. A candidate pool this big is unprecedented in modern New York City politics, as is the very nature of this race: a citywide special election for a second-tier job in the middle of winter. The 17 remaining candidates are facing some serious challenges: standing out from the crowd, turning out voters and not burning out.

New York City has seen slightly less dismal turnout in recent elections, which experts credit to the Trump effect. But there’s no telling if that will be a factor in this race, since it’s outside of the normal election cycle. With expected low turnout and a crowded ballot, the winner is likely to need relatively few votes. So candidates will rely heavily on getting their core supporters out to the polls as well as partnering with labor unions and Democratic clubs who know how to get people to show up. They’re also scrambling to raise cash, bolstered by a public matching funds system that pays out as much as $8 for every dollar of individual contributions up to $250. They’re raising their visibility in other ways as well, with 10 candidates qualifying for the first of two official debates last week, and a second one scheduled for Feb. 20. Late last month, Williams became the first candidate to air a TV ad.

A candidate pool this big is unprecedented in modern New York City politics.

But who to vote for, especially when there seem to be more similarities than differences among the candidates? Almost all of them are progressives. All of them – conservatives included – have talked about being a check on the increasingly unpopular mayor. Candidates often appear at the same press conferences, united in opposition. Assemblyman Ron Kim and New York City Councilman Rafael Espinal Jr. both protested Amazon’s planned expansion into Queens on a frigid morning last month outside City Hall. At least three candidates showed up to support immigration activist Ravi Ragbir at his recent check-in with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The nonpartisan election requires candidates to come up with their own party lines, and several had to go back to the drawing board because their first drafts sounded too similar. Assemblyman Michael Blake got to keep “For the People,” but his claiming of the term “people” meant that Williams’ “People’s Advocate” had to go, as did Kim’s “People Over Corporations” and Nomiki Konst’s “Pay People More.”

The campaign will be over before the end of February – but only if you want it to be. The winner of the special election will only be public advocate until November, when the position will be on the ballot again. And petitioning for the June primary begins Feb. 26 – the same day as the special election. Candidates who have been burning the candle at both ends, going to two public forums a night and flyering at subway stops in the morning, will barely get a reprieve. The race, and the work, never ends. You can’t blame Williams for slipping out of his chair to take a breather on the floor.

PICKING A PUBLIC ADVOCATE

Melissa Mark-Viverito

Party line: Fix the MTA

Ballot position: 1st

Home base: East Harlem, Manhattan

Job: Former New York City Council speaker, former Latino Victory Fund PAC senior adviser

Money raised, as of Jan. 21: $345,742

Key endorsement: Rep. Adriano Espaillat

Why she’ll win: Diversity – as the only Latina in the race – and experience. Council speaker arguably is the best preparation for being public advocate. That job, which she held from 2014 through 2017, gave her decent name recognition among voters.

Why she won’t: Her campaign failed to qualify for matching funds, suggesting she’s lacking grassroots support. And the job of council speaker opens her up to a lot of criticism – with current City Council members disparaging her leadership. She also was elected speaker thanks to de Blasio’s strong backing – raising questions about how aggressively she would take on the mayor.

Backup options: Run for governor of Puerto Rico, mount a primary challenge against Rep. José E. Serrano, or perhaps something else entirely.

Michael Blake

Party line: For the People

Ballot position: 2nd

Home base: Melrose, Bronx

Job: Assemblyman; Democratic National Committee vice chairman

Money raised, as of Jan. 21: $1.04 million ($324,029 + $716,133 in matching funds)

Key endorsement: Rep. José E. Serrano

Why he’ll win: He’s got more money than anyone, and is the lone Bronxite in the race, which could swing voters. He’s got an inspired way of speaking, and as a former campaign manager, he’s a wiley political operator.

Why he won’t: His naked ambition leaves no doubt he’d use the position to aim for something higher, which could bother some voters. And Blake’s always been more focused on national politics than local, leaving him wanting in local connections.

Backup options: Whatever allows the ambitious young politician to climb the political ladder.

Dawn Smalls

Party line: No More Delays

Ballot position: 3rd

Home base: Flatiron, Manhattan

Job: Partner at Boies Schiller Flexner; former U.S. Department of Health and Human Services executive secretary

Money raised, as of Jan. 21: $818,741 ($244,105 + $574,636 in matching funds)

Key endorsement: Executive Women for Her

Why she’ll win: She’s putting up impressive fundraising numbers. And though she’s never held elected office before, she’s got a stellar Democratic resume, with stints in the Obama and Clinton administrations and at George Soros’ Open Society Foundations.

Why she won’t: Her name has never appeared on the ballot before and has failed to earn any endorsements that could help drive turnout.

Backup options: Stay on as a well-paid lawyer at her white-shoe law firm.

Eric Ulrich

Party line: Common Sense

Ballot position: 4th

Home base: South Ozone Park, Queens

Job: New York City councilman

Money raised, as of Jan. 21: $100,712

Key endorsement: Queens GOP

Why he’ll win: He’s a Republican with a logical path to victory: If all the Democratic candidates split the vote, he could win, even with relatively few conservative voters. The Republican organizations in all five boroughs are backing him, and could help drive turnout. He might even win some Democratic votes with his pitch: “de Blasio’s worst nightmare.”

Why he won’t: He’s a Republican! In New York City! And fellow Republican Manny Alicandro could spoil his strategy.

Backup options: Follow through on a long-rumored run for mayor … bolstered by reality TV?

Ydanis Rodriguez

Party line: Unite Immigrants

Ballot position: 5th

Home base: Inwood, Manhattan

Job: New York City councilman

Money raised, as of Jan. 21: $134,996

Key endorsement: Bengal Democratic Club

Why he’ll win: An immigrant from the Dominican Republic, Rodriguez is appealing heavily to other immigrants-turned-voters like himself, and isn’t afraid to reference his thickly accented English as an asset in a city where half the workforce is foreign-born.

Why he won’t: Rodriguez has had a hard time earning respect in the council, and from voters, and will likely get crowded out by the higher-profile Latinos in Mark-Viverito and Espinal. Even Rep. Adriano Espaillat, a fellow Dominican and a longtime ally, didn’t endorse him!

Backup options: Manhattan borough president in 2021.

Daniel O’Donnell

Party line: Equality for All

Ballot position: 6th

Home base: Morningside Heights, Manhattan

Job: Assemblyman

Money raised, as of Jan. 21: $99,605

Key endorsement: Stonewall Democratic Club of New York City

Why he’ll win: Elected in 2002 as the first openly gay assemblyman, O’Donnell has been in public office longer than any of the other candidates, and has the relationships to prove it.

Why he won’t: O’Donnell has never been particularly prominent in the Assembly, he’s short on cash and voters may shy away from electing another white man to a citywide position – with de Blasio as mayor, Scott Stringer as comptroller and Corey Johnson as City Council speaker.

Backup options: Pass progressive legislation in Democratic-controlled Albany.

Rafael Espinal

Party line: Liveable City

Ballot position: 7th

Home base: Cypress Hills, Brooklyn

Job: New York City councilman

Money raised, as of Jan. 21: $172,537

Key endorsement: Teamsters Joint Council 16

Why he’ll win: After launching the city’s office of nightlife, Brooklyn’s young, cool, councilman has a lot of cred among voters who stay out dancing till 2 a.m., as well as those opposing Amazon’s expansion into Queens.

Why he won’t: He’s relatively inexperienced, short on endorsements and battling the widespread notion that he’s just running to raise his profile for a future run.

Backup options: Brooklyn borough president in 2021.

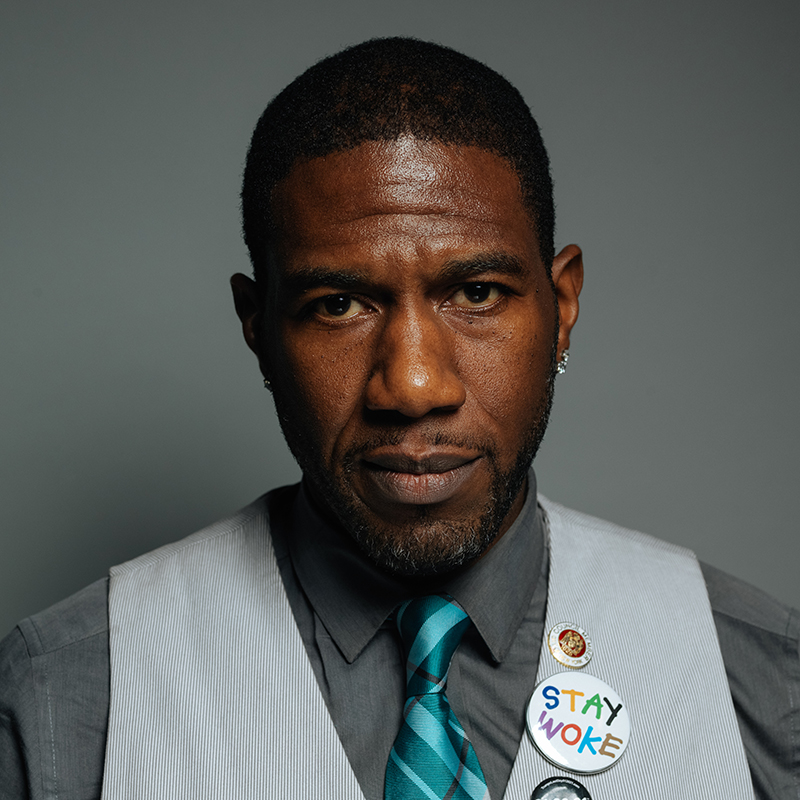

Jumaane Williams

Party line: It’s Time Let’s Go

Ballot position: 9th

Home base: Flatbush, Brooklyn

Job: New York City councilman

Money raised, as of Jan. 21: $886,101 ($195,907 + $690,194 matching funds)

Key endorsement: Working Families Party

Why he’ll win: Williams challenged Lt. Gov. Kathy Hochul last year, and actually beat her in New York City, 434,393 to 375,055. That race raised his profile and proved that voters see him as a viable counterbalance to the establishment in power. He’s running on the same platform in this race and has more major endorsements than every other candidate.

Why he won’t: The field’s full of lefties, and not as straightforward as last year’s two-candidate LG race. All the other candidates are attacking him as the presumed front-runner and some of the hits may sting, such as those on his mountain of personal debt or his past opposition to same-sex marriage and abortion rights.

Backup options: After running for council speaker, lieutenant governor and public advocate, see what office opens up next.

Ron Kim

Party line: No Amazon

Ballot position: 10th

Home base: Flushing, Queens

Job: Assemblyman

Money raised, as of Jan. 21: $186,886

Key endorsement: Assemblywoman Yuh-Line Niou

Why he’ll win: Kim’s aiming for the anti-Amazon vote, and the grassroots movement opposed to the deal seems legitimately strong. As a Korean-American, Kim could also turn out Asian-American voters, a constituency that has been underestimated before.

Why he won’t: It seems like all the candidates are opposing the Amazon deal. And Kim’s wife Alison Tan failed to unseat City Councilman Peter Koo in 2017 – in a race in which Gov. Andrew Cuomo endorsed the incumbent.

Backup options: Pass progressive legislation in Democratic-controlled Albany.

Nomiki Konst

Party line: Pay Folks More

Ballot position: 13th

Home base: Astoria, Queens

Job: Former anti-IDC activist; former “The Young Turks” investigative reporter

Money raised, as of Jan. 21: $95,964

Key endorsement: Millennials for Revolution

Why she’ll win: She’s a democratic socialist calling for a $30 minimum wage, and could use her impressive online presence – stronger than any of the other candidates – to hype up young leftists enough to vote.

Why she won’t: She has little money, little experience as a candidate, and although a Susan Sarandon endorsement is cool, it’s unlikely to turn out voters.

Backup options: Keep building her celebrity as a progressive voice on TV and social media.

ALSO RUNNING:

The seven remaining candidates, who didn’t raise and spend enough money – nearly $57,000 – to qualify for the first debate, include:

Benjamin Yee, a minor folk hero of the anti-machine left who holds regular trainings for New Yorkers interested in getting involved in hyperlocal politics, dipping his toe into campaigning for the first time.

Manny Alicandro, an unabashedly pro-Trump Republican attorney who briefly sought the Republican nomination for state attorney general last year before bowing out of the race.

David Eisenbach, a historian and professor running on an anti-REBNY platform who fell to Letitia James in the 2017 Democratic public advocate primary.

Jared Rich, a bombastic Court Street lawyer running for office for the first time.

Tony Herbert, a Brooklyn community activist who briefly ran for public advocate in 2016.

Helal Sheikh, a former teacher who emigrated from Bangladesh and unsuccessfully ran for City Council in 2013 and 2017.

Latrice Walker, an assemblywoman and Letitia James ally who suspended her campaign in late January but couldn’t get her name off the ballot.