“What the wolf lacks in size, power and weapons it makes up for with collaboration and intelligence.” – Living with Wolves

Emma Wolfe was dealing with another Cuomo crisis. It was a Friday morning in September 2015, and Gov. Andrew Cuomo was asking – or rather, demanding – that Wolfe’s boss, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, multiply the city’s contribution to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s capital plan. De Blasio was feeling stressed, and emailed his inner circle demanding a game plan for their response. Wolfe at the time was officially his director of intergovernmental affairs, and unofficially his most trusted political aide. Though de Blasio included six senior aides on the emails, Wolfe responded, speaking for the team. Her messages were deferential, but concise. She considered political tactics, and appealed to the mayor not to wait – to go on the offensive.

“The state wants us reacting, dragging this out and making us passive rather than active,” she wrote, “and they do not want us proposing sensible solutions with real conditions; a superior policy, message, and opportunity for coalition.”

Wolfe made a “fair point,” the mayor wrote. De Blasio and Wolfe went back and forth, talking tactics. The mayor said he wouldn’t want to pay the full $3 billion, or “become the bad guys for doing less.”

“Roger that – a strategy you can believe in,” she wrote. “I just really want to start pounding on the organizing.”

But de Blasio wasn’t fully satisfied. “I totally want you organizing our allies,” he said, “but I think we’re missing that this could end badly.”

So Wolfe asked for help. “Need your brain. A lot,” she emailed Jonathan Rosen, co-founder of the communications firm BerlinRosen and perhaps the mayor’s closest adviser outside of City Hall. “Any chance (you could meet in the) first half of week?”

Wolfe and Rosen set a date. Tuesday evening, 8:30 p.m., in Brooklyn.

These private emails exchanges between City Hall and Rosen were released only after NY1 and the New York Post sued to access them.

Two weeks after the email exchange, de Blasio’s team averted disaster. The city increased its contribution to the MTA, but not to the full $3 billion the governor had wanted. The New York Times framed it as a compromise, a rare victory for cooperation between the governor and the mayor – and a win for straphangers. Wolfe’s organizing seemed to have worked.

Wolfe has been described as de Blasio’s right hand, his consigliere and his shadow

Emma Wolfe is still organizing for de Blasio. Promoted to chief of staff for the mayor’s second term, Wolfe manages a large pack – the sprawling governmental apparatus that is City Hall. But she’s no alpha dog. In an interview with Wolfe at City Hall, and in conversations with more than a dozen people she’s interacted with in the political world, from operatives to elected officials, it became clear she’s widely respected for her political intelligence and her accessibility. Not everybody can call up the mayor. But everybody, it seems, can call up Wolfe.

“I certainly have a job to do when it comes to representing the views of the mayor,” she told City & State. “Clearly communicating. Maintaining a relationship with as many people as possible.”

These relationships have been at the center of some of the de Blasio administration’s biggest headaches, fueling critics who say she’s too accessible to donors like restaurateur Harendra Singh and lobbyist James Capalino. But Wolfe has de Blasio’s trust.

And unlike her boss, everyone who knows Wolfe seems to like her.

“Nothing but gracious,” said state Senate Majority Leader John Flanagan, who’s no friend of the mayor.

“Emma is a straight shooter,” said New York City Council Speaker Corey Johnson, who is also not afraid to criticize the administration. “She is really the go-to person when you can’t, or maybe shouldn’t, speak directly to the mayor but need to bring an issue to the forefront or try and solve a vexing problem.”

State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli likewise had only praise.

“One of the smartest people out there,” he said. “One of the most pleasant people as well. Which not often goes together for political geniuses.”

Wolfe, 38, has perpetually mussed light brown hair and wears dark, rectangular glasses. She has a unique sense of style, favoring suits and collarless dress shirts buttoned all the way to the top. It gives her the look of an eccentric college professor – but a very young one, with clear skin and bright eyes. At 5’3”, she’s more than a foot shorter than her towering boss. Wolfe has been described as de Blasio’s right hand, his consigliere and his shadow. If the latter, she would be much more of a midday shadow than the long, late-in-the-day type.

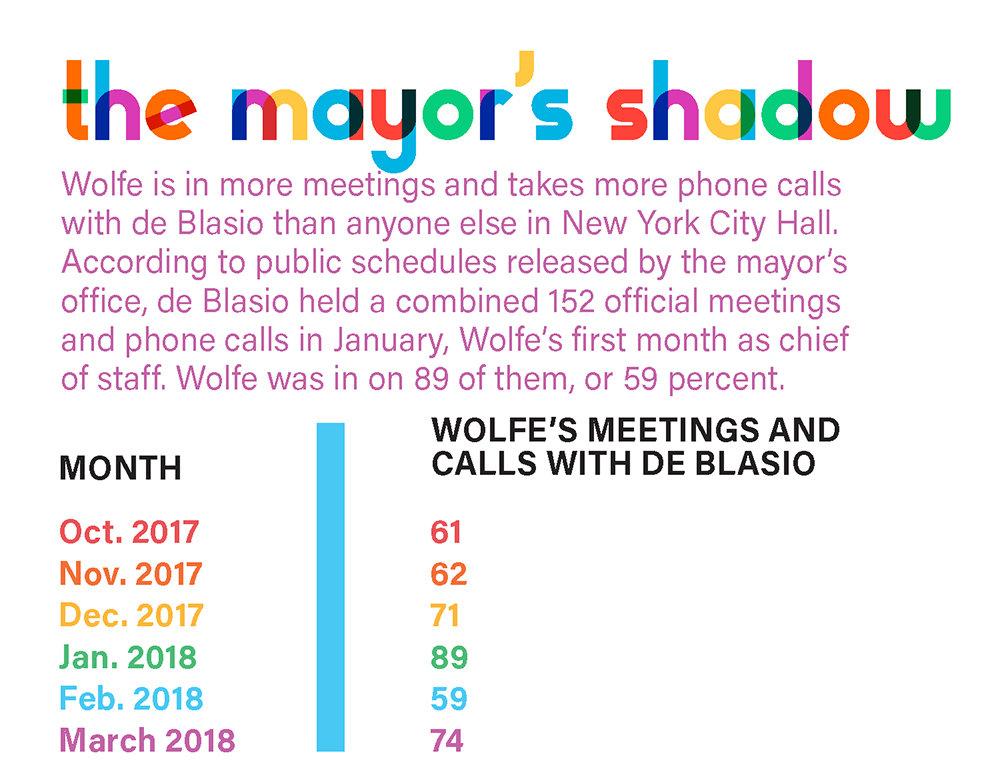

But on some days, the shadow comparison seems literal. On a Saturday morning in November, Wolfe joined on a phone call with de Blasio and 11 other senior advisers. Eight City Council members were in the midst of a two-month public scramble for the speakership. Though the speaker is elected by fellow council members, the mayor has some influence over the race, and de Blasio wanted a say. He held calls and meetings all day, according to public schedules released by the mayor’s office. After the call, de Blasio and Wolfe talked privately for 10 minutes before jointly meeting with Bronx Democratic County Committee Chairman Marcos Crespo at 11:40 a.m. Then the mayor had another meeting. And another and another. Nine in total, until 5 p.m., and Wolfe was there for all of them.

Indeed, Wolfe has more contact with de Blasio, in meetings and phone calls, than anyone else in City Hall. In March, the most recent month for which public schedules were available, she met with the mayor 74 times, far outpacing other staffers. First Deputy Mayor Dean Fuleihan talked with de Blasio 43 times; press secretary Eric Phillips, 40 times; and first lady Chirlane McCray, 21 times. And the public schedules, unreliable as they are, don’t show the full picture. Wolfe says her time isn’t limited to what’s on the public schedule.

“There’s definitely some organic nature to the schedule,” she said. “I’m in and out throughout the day.”

With all this time with the city’s executive, does Wolfe feel powerful? She demurs. “(Power is) not something I particularly relate to,” she said. “I certainly feel a great sense of responsibility.”

In the interview at City Hall, Wolfe frequently gave indirect answers. She seemed uncomfortable talking about herself, lacking the self-assured, practiced answers of a politician (a job she respects, but “couldn’t do”). She’s businesslike and admittedly all-consumed by her job, which seems to leave little time for self-reflection. On her clothing: “I do not know how I would describe my style remotely.” On the first time she met de Blasio? She might have shook his hand in 2001. On her sexual orientation? Agnostic about how she is described. “Queer, lesbian, gay. All three of those words, any three of those words,” she said.

Wolfe has been in a relationship with Stephanie Yazgi for 10 years, and the couple shares a home in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn. Yazgi is an organizer too, with a resume that mirrors Wolfe’s in many ways – including a job in City Hall. Yazgi’s 2015 hiring to a well-paid, newly created position in the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs made some think Wolfe’s influence had gone too far. But Yazgi was approved by the city Conflicts of Interest Board, even if she would work alongside Wolfe sometimes. She left City Hall within two years, and now works at the Center for Popular Democracy.

Despite being one of the most powerful queer people in New York politics, Wolfe hasn’t been involved with LGBT political groups since being an on-and-off member of the Lambda Independent Democrats of Brooklyn years ago. She says she would like to someday, but simply can’t find the time. In fact, she rarely attends any political club meetings and never joins in the happy hours or schmoozes at the cocktail parties for the city’s political insiders – unless she’s with the mayor.

It’s one of the ways Wolfe differs from other political consiglieri. She’s not the gruff enforcer that Joseph Percoco once was to Cuomo, nor does she defend her boss in the public square like Melissa DeRosa does for the governor. Wolfe isn’t the charming life coach that Erik Bottcher is to Johnson. Nor is she the stone-faced negotiator that City Council Chief of Staff Ramon Martinez is.

Wolfe is a quieter type, but still plugged into New York’s political pulse. She’s dependable to the mayor, her political partner for nearly a decade, and passionate about the same progressive causes. She is the mayor’s gatekeeper, but accessible to anyone who needs her.

That style has won her fans. Her counterpart across City Hall, Martinez, broke his “no comment” rule for this piece.

“I love Emma Wolfe!” he said. “She’s solid. She’s real.”

Wolfe was raised in Massachusetts and came to New York to attend Barnard College. She got into politics after taking a class taught by Gale Brewer, now the Manhattan borough president. Brewer guided Wolfe toward community organizing and connected her with Jon Kest, who led the progressive group ACORN, and was happy to take on a young organizer eager to work long hours. She graduated in May 2001, just ahead of the hotly contested New York City elections. She hit the streets for the Democratic mayoral candidate Mark Green, getting firsthand experience of how community organizations were integral to campaigns and government – even in a losing effort. She never left organizing, working for the national labor union Service Employees International Union and the local 1199SEIU, having a short stint in the state Senate and then joining the progressive-leaning Working Families Party, first as organizing director, then as elections director, a role in which she was credited with helping Democrats gain the state Senate majority in 2008 for the first time in decades. In 2009, she helped elect a progressive slate of candidates – including de Blasio, who won the race for public advocate and hired Wolfe as his chief of staff. She had her biggest win in 2013, helping lead her long shot candidate to the mayor’s office, where she’s been ever since.

Wolfe takes relationship-building seriously. She’ll check in with people on the City Hall steps. She’s visited most City Council members in their districts, walking around, coffee in hand, to hear what’s going on in their world. People bring their problems to her, and Wolfe listens.

“The only thing she has been to me is helpful,” said City Councilwoman Carlina Rivera. “Overall, that office is not responsive. She is.”

Wolfe is who lawmakers go to when they need to talk to City Hall, City Councilman Donovan Richards agreed.

“She’s knowledgeable. She’s very personable,” he said. “If you want something done, you can reach out to her. She’s a person of her word. You can disagree with her respectfully.”

But Wolfe’s pleasant demeanor isn’t part of a grand political calculation. She seems genuinely idealistic.

“Most people are very well-intentioned – it would be hard to have very antagonistic relationships with folks,” she said.

Even Cuomo, who has a notoriously strained relationship with City Hall?

“I don’t have an enemies list,” Wolfe said simply. Then, either by coincidence or by design, Wolfe took on the question-and-answer rhetorical device, hypophora, that is a favorite tactic of the governor.

“Are there relationships that are antagonistic in politics?” Wolfe asked herself. “Yes. Would somebody in my position be expected to have some of those relationships? Sure. Is there anything off the top of my head where I have that? No.”

“Overall, that office is not responsive. She is.” – City Councilwoman Carlina Rivera

But some relationships have gotten Wolfe in hot water. Because of her role at de Blasio’s right hand, Wolfe seems to have been involved in nearly every controversy about access and coordination in de Blasio’s City Hall. Wolfe was a major player in “Team Coordinated,” a progressive coalition that was accused of breaking various election laws in raising money for three Democratic state Senate candidates in 2014. That got her subpoenaed. She may have fast-tracked paperwork to lift the deed restriction on a Lower East Side nursing home represented by major de Blasio donor James Capalino – an action which later allowed it to be sold for a profit to condo developers. And she took on the case of another major de Blasio donor, Harendra Singh, who was having trouble renewing his Queens restaurant’s lease with the city. Singh later pleaded guilty to bribing the mayor – using his campaign donations as leverage for favorable treatment.

None of these cases resulted in charges against Wolfe, or anybody in the mayor’s office, but questions about City Hall’s way of doing business remained, even for prosecutors. In a March 2017 memo announcing his office would not prosecute the mayor, acting U.S. Attorney Joon Kim noted that de Blasio “and others acting on his behalf,” like Wolfe, solicited donations from people seeking “official favors from the City.” A memo released the same day from Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. was even more direct, noting that the state Senate fundraising Wolfe was involved in appeared “contrary to the intent and spirit of the law(s)” meant to prevent corruption.

Wolfe has remained mum on all the cases. De Blasio press secretary Eric Phillips defended City Hall in a statement provided to City & State. “Policy decisions by this administration are made on the merits and there’s zero evidence to suggest otherwise,” he said.

De Blasio himself has been as good as silent about Wolfe. After court records were unsealed in January that showed Singh had pleaded guilty, reporters at an unrelated press conference asked de Blasio three times about Wolfe’s involvement in Singh’s business with the city.

“I want to be really clear, everything we did on that matter and everything else we’ve done in this administration was legal, was appropriate, we hold ourselves to high ethical standards,” he said the first time.

Asked twice more about Wolfe, he brushed it off: “Got nothing more to say on it.”

Wolfe has never lost de Blasio’s trust. He previously called her “the great strategist,” and once, at an LGBT pride reception, a “power lesbian.” But at the press conference announcing her promotion to chief of staff, de Blasio was at a loss for words.

“Emma has – it’s –” the mayor stumbled. “I could not tell you everything I feel and believe in about Emma Wolfe unless I kept you here all day.”

Wolfe has been around de Blasio longer than most. When you look at emails among senior staff from the beginning of his mayoralty, she’s one of few that still works at City Hall. She’s loyal to the mayor without seeming sycophantic, and sees her role as essential. “The goal is to put him in the most optimal space to be able to make tough decisions, to be able to get in front of the public and perform well,” she said.

After nearly a decade by de Blasio’s side, does she know what he’s going to say before it comes out of his mouth?

“I think I can anticipate a lot of what he may be concerned about, the kinds of questions he asks, that sort of thing,” she said. “But I would never say I could read his mind.”

Correction: The original version of this story misspelled Jon Kest's name.

NEXT STORY: Who's up and who's down this week?