The evidence of contamination was there in black and white – until it disappeared.

The New York City Housing Authority’s handwritten “Annual Roof Tank Inspection Reports” chronicle a history of tainted drinking water tanks that the housing agency failed to report to city health officials, according to an examination of hundreds of internal NYCHA documents and New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene records.

The details are there in the field reports, but they’re gone in the health reports.

Inside a stack of hundreds of internal NYCHA documents, vivid details of contamination leap off dozens of pages – dead birds and squirrels, flying insects, and things floating and growing inside NYCHA’s many damaged wooden drinking water tanks. But the documents also show that evidence of potentially hazardous conditions in its water tanks was blotted out using white-out under a recent policy change that appears to have had a chilling effect. Some tank inspectors say they don’t even write down the dirty details anymore.

Even the unsanitary conditions that remain unambiguously documented on the internal reports are nowhere to be found on NYCHA’s water tank inspection filings with the city health department. This pattern repeats itself in tank after tank, atop building after building in the vast forest of low-income apartment towers maintained by the agency.

“Some of the worst tanks in the city are in the housing projects,” said David Hochhauser, who runs Isseks Brothers, one of three companies that specialize in building and cleaning wooden drinking water tanks. Hochhauser said he stopped working with the agency because of the red tape, a sense that it wasn’t worth the time, and the unpleasantness of the job. Indeed, tank cleaners that currently clean and inspect the tanks have complained about NYCHA’s tanks to this reporter for years.

Still, the NYCHA water tank contracts are among the most valuable in the city, worth millions of dollars a year – a search of city records showed several such contracts have been awarded for a total of $63 million since 2016 alone.

In an industry dominated by just three companies who know how to build the barrel-like tank structures, there is a strong disincentive to say anything that might imperil a contract renewal. City & State spoke with a half dozen tank company employees for this story, many of whom agreed to speak only on the condition of anonymity.

“Whenever we find a bird in the tank, 9 times out of 10, it’s NYCHA,” said a tank company employee in 2014, who requested anonymity to speak without authorization. Earlier this year, another tank cleaner said little had changed. “New York City housing tanks are the worst,” he said.

In fact, many of the bleakest stories recounted by the tank company employees stem from their experience on the rooftops there. In 2012, a man living inside a NYCHA water tank with a sleeping bag used a neighboring water tank as his personal toilet, tank company employees said. Just this July, immediately before a pipe burst and left nearly 900 apartments without water, another homeless man was found inside the drinking water tank at Brevoort Houses in Brooklyn during an annual roof tank inspection and cleaning, according to Pansy Nettles, Brevoort’s resident association president. It’s unclear whether either of these incidents were recorded by tank cleaners in their reports as they fell outside the scope of City & State’s records request.

NYCHA has acknowledged a history of mismanagement and neglect of its deteriorating housing developments, including allowing mold to fester and paint to peel in tenants’ apartments. But even as federal prosecutors investigated the agency for falsifying lead paint certifications, it appears NYCHA has also been hiding deteriorating conditions in its drinking water tanks.

When asked about the discrepancies between the field reports and the health department filings, a NYCHA spokesman said, “NYCHA will update its current Annual Roof Tank Inspection Report to reflect the current condition of the tank at the time of the inspection and any corrective action taken will be noted in the report.” Responding to the deteriorating conditions in the tanks, the spokesman said, “We are working to address our repair process to ensure expediency.”

In a later statement, a NYCHA spokeswoman added, “While our water tank cleaning and inspections are reliable, we will review the filing of our inspection forms to ensure they reflect this effort accurately.”

Dark water, the color of black coffee, spurted out of Maria Santos’ kitchen faucet.

Santos, 67, filled up a cup with the liquid. She took a picture of it and marked the time: 10:54 a.m. She wanted the evidence. She says this happens two or three times a month in her third floor apartment at the Chelsea Houses Addition, a NYCHA building for elderly tenants. The water has been so silty that maintenance workers have had to unclog her faucet. Santos says she’s afraid to drink her building’s water and often feels nauseous when she does. She saves up to buy bottled water, but she can’t always afford it.

Several other tenants in the building said they had similar experience with brown water. Door after door opened and elderly tenants shook their heads when asked about their water. “It’s no good,” a wheelchair-bound woman on the 14th floor said. “Oh my god, the water,” said Jose Perez on the 12th floor. Then, with a stern, knowing stare, he said, “You open the water. And brown.” Rusty pipes are most often the cause of brown water, but it seems Santos is on to something else too.

“They always claim to be cleaning the water in that tower,” Santos said of the rooftop drinking water tank on her building. “But they don’t seem to do a very good job.”

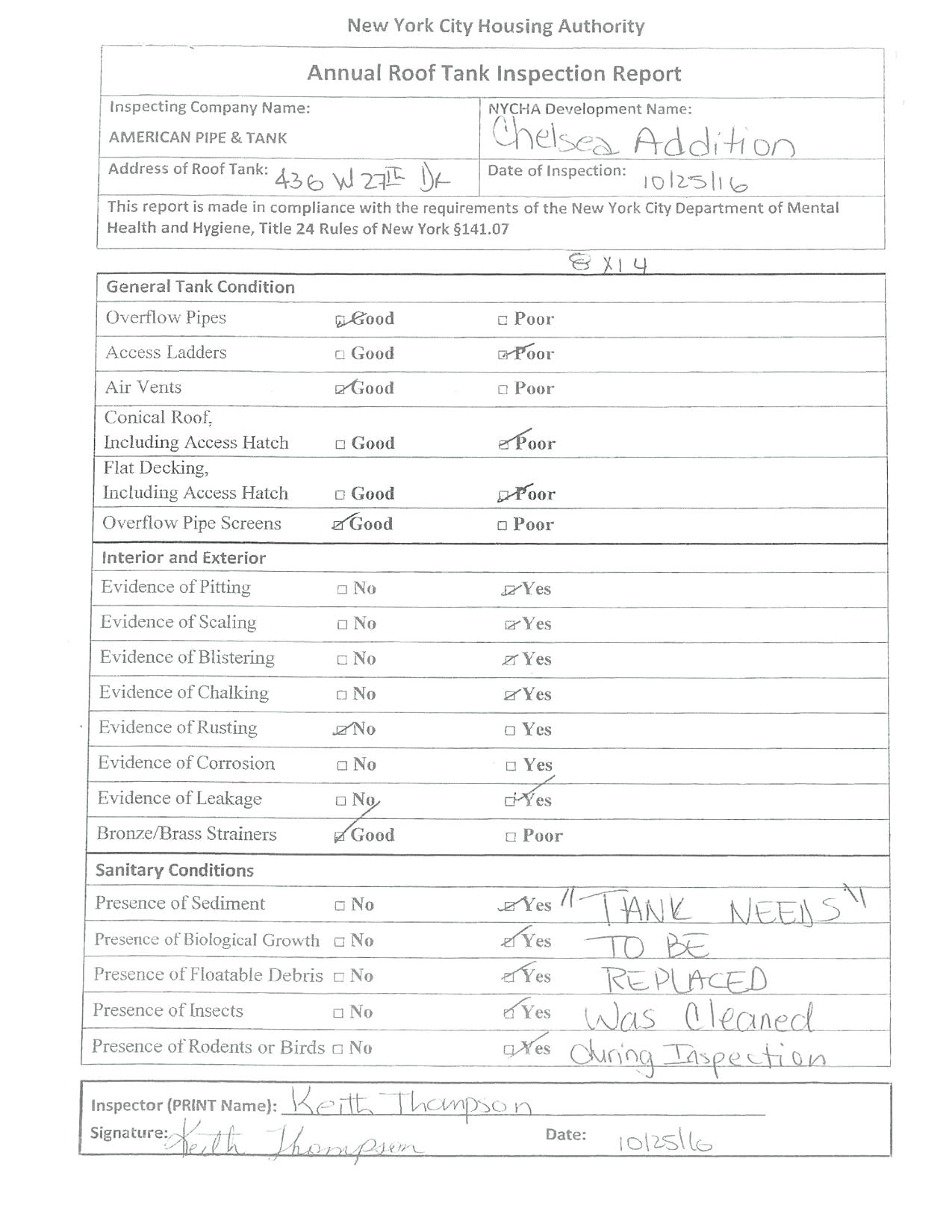

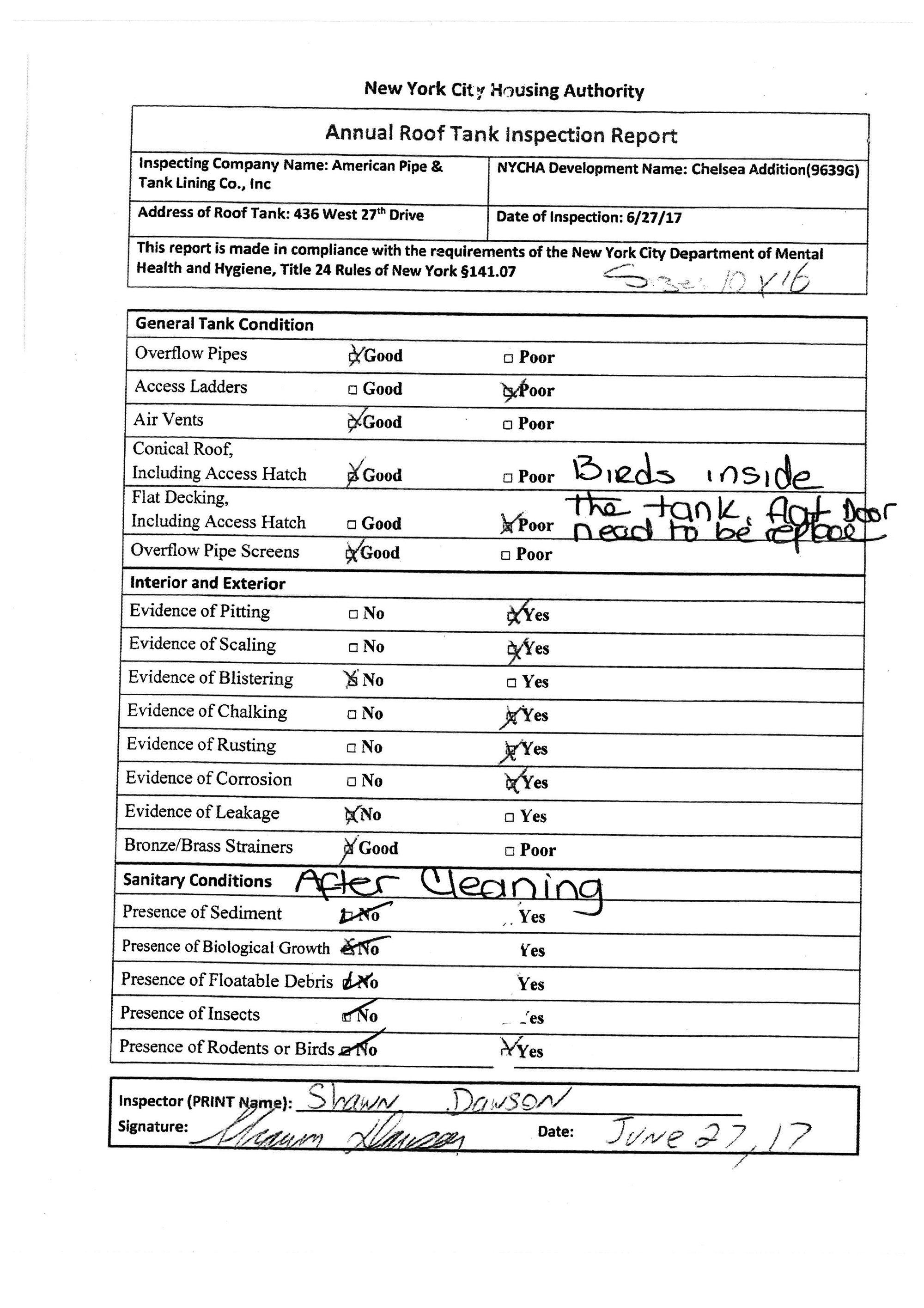

The dirty water in their building is symptomatic of a drinking water system plagued with problems. High above the tenants’ heads, rooftop tank cleaners have repeatedly found serious sanitary problems inside the wooden water tank that supplies drinking water to their apartments on West 27th Street in Manhattan, according to the records obtained by City & State.

For two consecutive years, in 2016 and 2017, the men who climbed inside to clean the barrel-like tank found “sediment,” “biological growth,” “floatable debris,” “insects,” and “birds or rodents” in the unfiltered water reservoir elderly residents use for drinking and washing. A handwritten note on an internal NYCHA inspection report from 2017 reads: “Birds inside the tank, flat door need to be replaced.”

City & State obtained hundreds of internal NYCHA water tank inspection forms through a records request with the agency. Those handwritten papers, filled out by water tank cleaners during the physical examination of the tank, were then compared to the electronic inspection filings NYCHA submitted to the city health department. City & State’s analysis discovered dramatic differences between what the tank men saw and what the health department was told.

In the more than 600 NYCHA inspection forms dated between 2015 and 2017, 47 reports describe a parade of pollutants catalogued by the water tank cleaners, including “flying insects,” “plastic bag,” “deceased squarel,” and “dead birds.”

The Elliott development’s graffiti-tagged water tank at 426 West 27th Drive, next door to Santos’ apartment building, also had serious problems: “Birds & Insects inside Need new cover.” The tank cleaner then marked “Poor” beside a line item documenting the condition of the metal strainer covering the domestic downfeed pipe, which sucks water down into apartments. In barely legible writing, it notes the strainer was missing, and appears to say that there were “Birds in drain.”

Yet, none of these worrisome details made it into the reports NYCHA filed with the department of health. While the health department’s form does not allow for descriptive text, it does specifically ask if birds, rodents, or insects were found, but NYCHA did not once indicate their presence.

These discrepancies provide important context for an internal policy change, acknowledged by NYCHA, within the last year, that has had the effect of limiting what details are recorded.

Two water tank company employees described a meeting they attended with NYCHA’s environmental and fire safety units in which a compliance official instructed the tank companies to stop recording unsanitary conditions found in the wooden water tanks in the “Sanitary Conditions” section of the form. The employees said they now use white-out to redact field observations testifying to the presence of birds, rodents, insects and mucky sediment and biological growth inside the rooftop drinking water reservoirs if those things are noted in the “Sanitary Conditions” section. But, one said, they preserve those details by rewriting them higher up on the form.

Nevertheless, a different tank cleaner said the impact of the policy change was broader.

“We don’t write anything down,” said a water tank cleaner, who requested anonymity so he wouldn’t jeopardize his job. He said NYCHA officials have made it clear to him that he should not record the worrisome problems he finds.

“We don’t specify what we find in there,” he said. “We don’t write it, because nobody likes that.”

NYCHA confirmed the policy meeting occurred and the general roles of those involved. When asked for more information about what happened at this meeting, including whether the health department was consulted on the policy change, a NYCHA spokesman responded via email in all caps, “WE ARE NOT GOING TO PROVIDE THESE DETAILS TO THE DELIBERATIVE PROCESS OF POLICY MAKING.”

NYCHA says the decision to instruct tank cleaners to describe what was in the tank only after it was cleaned was to “assure that the mechanics follow the cleaning procedure.” When asked to explain how that would help them follow procedure, a NYCHA spokesman explained that if tank companies noted an unsanitary condition on the form, “NYCHA staff reviewing paperwork did not have any confirmation that the condition cited was corrected. That is why it was asked of the vendor to tell us on the form the condition after cleaning.”

After receiving questions from City & State, however, NYCHA appeared to revise its policy position.

“NYCHA will update its current Annual Roof Tank Inspection Report to reflect the current condition of the tank at the time of the inspection and any corrective action taken will be noted in the report,” the spokesman said.

When asked how it addresses the appearance that its policy seeks to cover up recurring sanitation issues, the NYCHA spokesman did not answer the question. Instead, he reiterated that NYCHA requires tank cleaners to clean and maintain the tanks, as city law has mandated for years.

“Our policy requires any unsanitary issue found to be corrected by the vendor during the cleaning process. Those that cannot be corrected immediately due to repairs being needed are forwarded to the Development to correct,” an emailed statement read.

NYCHA’s policy evolved over the past several years, moving steadily away from encouraging cleaners to document sanitary problems. While many 2014 water tank inspection forms printed in bold across the top “NOTE: Provide comments for all deficiencies,” that language disappeared the next year. Newer forms feature “AFTER CLEANING” typed in all caps above the “Sanitary Conditions” section. According to the water tank company employees in the policy meeting, NYCHA officials told them that this section should not have any answers marked “yes,” indicating the presence of a sanitary defect, and should instead be marked “no,” because a tank should be free of any dead birds or muck “after cleaning.”

Reviewing NYCHA’s records, it appears at least 71 reports were clearly altered after the physical tank inspection, with evidence of white-out smeared over the form’s lines and check boxes. In those altered reports and others that were left unredacted, the following conditions were found inside NYCHA’s drinking water tanks: “floatable debris,” 30 times; insects, 17 times; “biological growth,” 18 times; and birds, 24 times.

Some of the altered reports may be honest corrections, tank cleaners note, but they also say that there have been forms filed to NYCHA that fail to mention contamination they saw inside the tank.

The city health department did not directly answer questions from City & State about whether the discrepancies between the contamination that tank cleaners saw in the tanks and the spotless inspection reports NYCHA filed with the health department were a concern or a violation of any laws or regulations.

In an emailed statement, a health department spokesman wrote,“The Health Department takes mandated inspection requirements very seriously. We are reviewing records, discussing with NYCHA and will provide guidance about water tank inspection requirements. Our main concern is that landlords are complying with water tank inspections and cleaning requirements – we can work with them on improving paperwork. There is no evidence that the water from water tanks raises any public health concern, and there has never been a sickness or outbreak traced back to a water tank.”

Water tank inspectors’ notes detail two consecutive years of contamination in a drinking water tank supplying an elderly-only NYCHA building in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood.

NYCHA is New York City’s largest residential landlord, providing housing for 1 in 14 New Yorkers. As such, it is also the city’s largest supplier of domestic drinking water to moderate- and low-income tenants. The housing authority is responsible for maintaining 224 rooftop drinking water tanks at 150 developments across the city. A common NYCHA water system includes a 20-foot tall wooden water tank mounted to highest point of the tallest building among a complex of brick apartment towers. Drinking water drains out of that one 30,000-gallon tank and flows through pipes to residents in all those buildings. And so, the wood water tanks are the last place drinking water is held before it flows into tenants’ sinks and showers, unfiltered.

The rooftop wooden water tanks are inherently vulnerable to contamination, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency experts previously told City & State in a earlier investigation of the city’s drinking water tanks. EPA scientists feared that the neglected tanks may be the source of disease outbreaks and criticized current tank inspections and water testing as inadequate. The EPA requested its individual scientists not be named.

“When you look at waterborne disease outbreaks in Gideon, Missouri, and Alamosa, (Colorado), there are three things that happened,” an EPA water tank expert previously told City & State, describing the deadly episodes in those places. “If you have sediment buildup, if you have a way that pathogens on animals and insects can get in, and if this sediment is stirred up somehow and is allowed to be used, then you have a real potential for an increase in endemic disease.”

That story revealed that as many as two-thirds of buildings with water tanks were not complying with city laws that mandate annual inspection, cleanings, and filing a form with the city Department of Health and Mental Hygiene that documents what the inspectors found in the tank.

In response, New York City Councilman Ritchie Torres triggered an inquiry by the city’s Department of Investigation to examine what Torres deemed “the city’s failure both as a regulator and an owner.” City & State previously found that one city agency in charge of caring for 55 municipal buildings, like courthouses, reported clean bills of health that appeared to contradict plainly visible problems, with one tank that has been slowly rotting away for years.

When it comes to water tanks, it appears government agencies in New York City charged with safeguarding the quality of drinking water inside buildings can be among the least likely to report potential health hazards or deteriorating conditions inside a tank.

Tank cleaners said that the underlying reason NYCHA’s tanks suffer chronic contamination is that structural damage – like a gaping hole in the roof of a water tank – often goes unrepaired for years.

"In the projects, you know what it is?” said a tank cleaner, referring to the NYCHA developments. “They don't take care of their tanks."

Many of NYCHA’s giant wooden tanks are visible from a mile away and others are thinly-veiled behind lattice masonry. But as conspicuous as they can be, the tanks have long been neglected and have fallen into disrepair, allowing animals to crawl inside and imperil the tenants’ water quality, according to tank cleaners and inspection reports.

Many of the tanks are around 30 years old and should be replaced immediately, employees at two different tank companies said. In fact, tank cleaners say that the root of the problems with water tanks at NYCHA boil down to delayed repairs and replacements.

Nearly every time cleaners find birds floating dead in the drinking water, they say it’s because the roof has collapsed or the wooden access hatch has blown away. They can scoop out the animals and rinse down the tank, but if the roof isn’t repaired, the birds will just fly right back inside the newly cleaned tank.

NYCHA’s internal reports show cleaners repeatedly warning NYCHA about the deteriorating conditions in the tanks: “Must be replace(d).” “New Hatch Door needed.” “Missing metal and peeling rotted hatch/supports.” “Lumber is spongy.” But because repairs were not included in the annual inspection and cleaning contract, tank cleaners say, superintendents and managers at each development have to approve repairs separately, often leading to a bureaucratic game of hot potato – the request bouncing from office to office, no one wanting to approve the additional expense.

Tank companies say that more often than not, over the years they seldom hear back about their request to repair a tank. Even though it seems to them that NYCHA has been increasing the number of repairs it approves, many times, the next time they see the tank is a year later and it still has the same problems.

The Chelsea Houses Addition NYCHA development is a prime example. After birds were found in the drinking water tank in 2016, tank cleaners warned, “TANK NEEDS TO BE REPLACED,” noting that the condition of the roof, access hatches and flat decking as “poor.” NYCHA officially slated it for replacement but nothing was done that year. In 2017, birds were again found in the water supply tank, according to an inspection report. To date, the drinking water tank has not been repaired or replaced.

Beatrice Sanderson, 80, who lives on the 13th floor of the building, said she is coping the best way she knows how. She uses a water filter and lets the water run in the morning for a while before she uses it. She wasn’t too surprised about the birds in the water tank. “I see them flying up there,” past her window, she said.

Her landlord has left a number of problems unfixed, she noted. “Lead paint, among other things,” she said pointing through her open front door towards a large patch of peeling paint. “They’re on the hot seat for a lot of things.” Among them, a backlog of tenant repair requests and falsification of records, as reported by the Daily News.

But beyond what the documents say about the condition of the tanks, there remains a question about how much has been left out of the record.

In 2014, this reporter observed a water tank atop an East Harlem NYCHA building at 165 E. 112th St. with a gaping hole in the conical cover where the access hatch had once been. The weather stripping was long gone and metal sheets were rusting and peeling off the roof. These problems had been noted in a 2013 inspection report, but feathers and droppings littered the inside of the tank’s plywood decking just above the drinking water supply.

From the available records, it appears two more years went by before NYCHA inspected that tank and those 2016 and 2017 reports show no structural or sanitary problems whatsoever. “AFTER CLEANING” is typed onto the 2017 report. Looking only at the paper trail, it is as if those sanitary problems never existed.

Some of the cleaners who climb inside the tanks have carefully documented the unsavory details of what’s in New Yorkers’ drinking water tanks, while others appear to have fallen into a culture of quietly sweeping away health hazards, hidden inside the water tanks.

One veteran water tank cleaner said that no one will tell you 100 percent of what they find in the tanks anymore.

“Yeah,” he said with a sigh. “Tricks of the trade.”

-with reporting by Kay Dervishi and Max Parrott

NEXT STORY: Will SHSAT debate help Liu or Avella?