New York State

New York’s pension funds still invest in guns, tobacco and oil

New York’s pension funds still invest in guns, tobacco and oil because divesting from controversial companies or industries is not so simple – even after high-profile incidents, such as the Florida school shooting in February that left 17 dead, increase the political pressure to do so.

Guns, cigarette and fossil fuels Pajor Pawel, Antonio Mas, Catalina M / Shutterstock

In January 2013, just weeks after the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, state Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli announced that he would freeze the state pension fund’s investments in gun manufacturers.

“The New York State Common Retirement Fund will not buy stock in companies whose primary business is manufacturing firearms for commercial sale,” DiNapoli said at the time. “After the terrible events in Newtown, it is clear that the national movement toward greater regulation of firearms manufacturers will impose significant reputational, regulatory and statutory hurdles that may affect shareholder value.”

By 2014, the fund had sold off its shares of Smith & Wesson Holding Corp., the country’s largest producer of pistols, and Sturm, Ruger & Co. Inc., America’s largest overall firearm maker.

The state comptroller has targeted other companies along similar lines.

“The Fund maintains specific ‘restricted lists’ of companies whose business practices pose an unjustifiable risk to the Fund,” a spokesman for DiNapoli wrote in an email. “The Fund has restricted lists regarding the following issues: tobacco, private prisons, gun manufacturers, Boycott/Divest/Sanction of Israel and certain lines of business in Iran and Sudan.”

But as a practical matter, divesting from controversial companies or industries is not so simple – even after high-profile incidents, such as the Florida school shooting in February that left 17 dead, increase the political pressure to do so.

Since the Sandy Hook shooting in 2012, the state’s massive retirement fund actually increased its investment in at least one gun manufacturer. Between 2016 and 2017, the fund doubled its shares of Olin Corp., a Missouri-based company that owns the Winchester brand of rifles and ammunition.

Unlike Ruger and Smith & Wesson, firearm sales make up only part of Olin’s business, and because of this, Olin is not on the state pension fund’s restricted list. While Winchester accounted for just 13 percent of Olin’s 2016 revenue, the brand is a major producer of small caliber ammunition, holding several contracts with the military, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and numerous other law enforcement agencies.

Additionally, the state comptroller is charged with ensuring a certain rate of return for public sector retirees, giving him little leeway to let politics determine his investment strategy.

The New York State Common Retirement Fund is worth more than $200 billion, and more than 1 million current and retired state employees pay into it and depend on it. The state comptroller is its sole trustee, and he’s legally bound to protect the interests of the fund’s participants above all else. That means the fund has to have enough money to continually pay everyone’s pension checks.

“As trustee of the New York State and Local Employees Retirement System, the Comptroller is charged with the fiduciary duty to manage and protect the retirement funds,” state Sen. Martin Golden, the chairman of the Civil Service and Pensions Committee, wrote in an email to City & State. “The Comptroller must act as a prudent investor. Assets in the retirement funds should be acquired and sold based on that standard, not a political agenda. The future of State and Local employees is at stake.”

Because of this, the tension between political considerations and the fund’s investment portfolio can be tricky to navigate.

In March 1996, then-state Comptroller H. Carl McCall declined to divest from tobacco stocks. However, he did agree to hold off on increasing the fund’s tobacco investments, citing the high potential for lawsuits against tobacco manufacturers, which could directly harm the values of those stocks and, by extension, the fund.

When running against McCall for the Democratic nomination for governor in 2002, Andrew Cuomo castigated the comptroller for not using the pension fund as a political tool and accused him of “social indifference.” (McCall eventually won the nomination before losing the general election to incumbent Gov. George Pataki.)

DiNapoli has been somewhat more willing to use the fund’s investments for political ends, including an attempt to pressure Chevron into settling a massive environmental lawsuit in Ecuador around 2011. More recently, he has been wary of divesting from fossil fuel companies, despite pressure from Cuomo.

“As a long term investor, we prefer engagement with companies to improve behavior on environmental, social and governance issues,” DiNapoli’s spokesperson wrote. “That’s our initial tool for reducing investment risks when we perceive a company is engaged in risky practices.”

Those overseeing New York’s pension funds also note that they don’t actually select many of the specific companies they invest in.

According to DiNapoli’s spokesperson, most of the state fund’s stock purchases were made as “passive” investments, in which the fund’s managers invest in index funds that contain stocks from hundreds or thousands of different companies from a wide variety of industries. In index funds, investors do not pick and choose individual stocks to purchase.

However, the fund does work with some external managers to pick specific stocks for “active” investments aimed at outperforming the market.

While the state fund’s restricted lists do not apply to its passive investments, the restricted lists of New York City’s five pension funds do. Unlike the state comptroller, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer isn’t the sole trustee of those funds, so he doesn’t have the same power that DiNapoli does. However, he does work with each fund’s board to plan their investment strategies, and can urge them engage with or divest from specific companies or industries.

“We actively engage companies to fight for responsible business practices that foster economic success. But we don’t hesitate to use every tool in the toolbox consistent with our fiduciary duties to the hundreds of thousands of city workers who count on us for a secure retirement,” Stringer wrote in an email. “That means, for us, engagement and divestment work hand in hand. And when we identify a threat to the long-term interest of the pension funds and we decide to divest, we remove the company from the entire portfolio, regardless of whether it’s in an active or passive account.”

Other pension funds are confronting the similar questions.

The New York State Teachers’ Retirement System, which is not managed by the state comptroller and is not subject to the same restrictions, held about $31.2 million worth of Olin shares and $2.6 million of Ruger shares as of Dec. 31. In December 2012, the fund held nearly $3.4 million and $3 million in Ruger and Olin, respectively, according to The Associated Press.

The Teachers’ Retirement System of the City of New York – one of the five funds overseen by the city comptroller – hasn’t held stock in Smith & Wesson or Ruger since 2012, while the New York City Employees’ Retirement System and the Teachers’ Retirement System are planning to divest of their fossil fuel holdings by 2022.

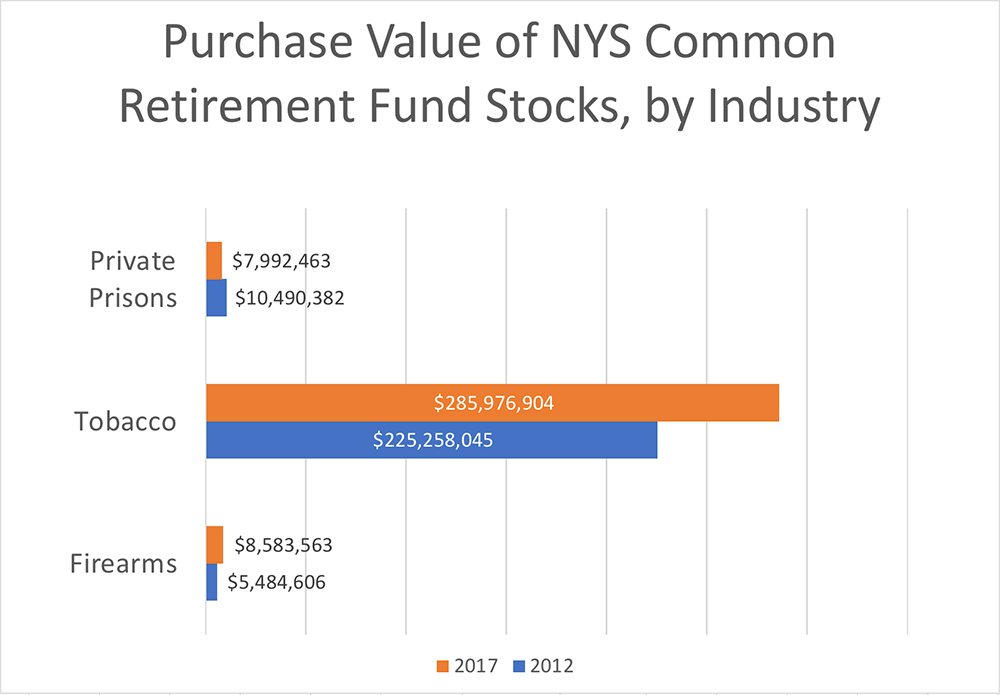

Tobacco manufacturers like Philip Morris, Altria, Reynolds American, British American Tobacco and Imperial Tobacco can all be found in the state fund’s 2017 portfolio, and its stake in Reynolds American doubled between 2015 and 2016. Likewise, the fund’s 2017 portfolio also included shares of GEO Group and CoreCivic, America’s two largest private prison operators. CoreCivic, which was known as Corrections Corporation of America until October 2016, was the subject of a high-profile investigation by Mother Jones that found widespread abuses in a privately run Louisiana prison. According to the state comptroller’s office, all of these were made as part of passive investments.

“Divestment is very complex and is a last resort when all other options are unsuccessful. Divestment requires a case-by-case economic analysis to determine whether divestment is in the best interest of the Fund,” DiNapoli’s spokesperson wrote. “Rarely has the Fund divested, and it did so only when satisfied that the Fund’s investment returns would not be negatively impacted.”

With reporting by Rebecca C. Lewis.

NEXT STORY: Bob Linn is watching the U.S. Supreme Court