Walking into the Phoenicia Diner on a warm, sunny June day, Gareth Rhodes, a 29-year-old former press aide to Andrew Cuomo and a congressional candidate in New York’s 19th District, which covers the Upper Hudson Valley, the Catskills and parts of Central New York and The Capital Region, was in safe Democratic territory. The diner is nestled between a lush forest and a mountain in Shandaken, New York. The hot spot for hip New York City transplants and vacationers serves avocado toast or a portobello caprese sandwich. The diners’ politics are as progressive as their taste in food.

With these Democrats, Rhodes discussed issues that are typical of a Democratic primary, including gun control and President Donald Trump’s tweets. One might expect Rhodes to do best in this environment, but these customers were not an easy sell.

Rhodes sat down with one woman, a retired artist who had not decided who she will support in the primary. Her top concerns? “Trump cuts to the National Endowment for the Arts,” she said. Also, affordable housing. “Lots of houses on the market are becoming Airbnbs.” The candidate duly promised to protect the NEA and pass regulations on the short-term vacation rental industry. She seemed unconvinced, but it was hardly Rhodes’ fault. With six other candidates in the race, all of whom claim to be firmly progressive, she has no shortage of alternatives.

But if the Phoenicia Diner shows the limits of Rhodes’ ability to win over typical liberal Democratic primary voters, his next stop reflected his unorthodox strategy to compensate for it. Rhodes is trailing Antonio Delgado, an attorney from Rhinebeck, by most measures. Rhodes is hoping to upend the race by bringing populist rural Democrats who don’t usually participate in midterm primaries out to the polls. Just by reaching out to them with a progressive economic message, he hopes to excite some sporadic voters and even some Trump voters. If Rhodes wins the primary on Tuesday night – and if he then succeeds in knocking off Republican Rep. John Faso in November – it will shed some light on whether such a strategy can help his party turn the tide against Trump.

Rhodes pledged to travel to all 163 towns in the district. Last week he completed his trek, and has further promised to hold town halls in every county during the election and once again visit all 163 towns each year if elected. All of this is despite the fact that many of these towns have no more than a few hundred residents. Most are also staunchly conservative.

If any Democratic can connect with them, it’s probably Rhodes or someone a lot like him. Tall and firmly built, with a head of straight brown hair, he campaigns in casual clothes instead of suits. Growing up on a farm near Kingston, New York, the district’s largest population center, Rhodes grew up more interested in hiking and fishing than smartphone games or streaming videos. He worked a job drilling water wells in his youth, volunteered as a firefighter and attended City College of New York on Pell Grants. Rhodes is no stranger to physical labor. Perhaps that’s one reason he has attracted the most union endorsements of any NY-19 candidate by far.

Rhodes rose to national prominence in mid-June, when The New York Times editorial board unexpectedly endorsed his candidacy. They called him, “the best candidate to take on — and beat — Mr. Faso in November,” because he “has listened closely to the woes of dairy farmers in dire straits, to families who have had to travel hundreds of miles to the closest maternity ward, to students struggling to pay off student loans.”

On the drive to Delaware County, which has voted Republican in all but two presidential elections since 1884, Rhodes demonstrated his knowledge of the bread-and-butter issues facing residents there. “What I’ve seen in my travels is that there is a municipal-rural crisis,” Rhodes explained, “people have left, the tax base has decreased, and as the tax base decreases, the ability to provide services decreases. As there are less services, more people leave and it becomes a spiral.” He has made issues like improving EMT and fire services in rural areas, bringing a maternity ward to Delaware County and increasing broadband access throughout the district central to his campaign.

At a small market and deli in Bovina – a town of just 650, named for its dairy farms – Rhodes met a group of nine women. Retired nurses, teachers and social workers with short gray and white hair in bob cuts. The market had a feel of old Americana, the walls lined with cans and packages – bags of licorice, local maple syrups and Saranac brand soda in glass bottles – that would have looked the same 40 years ago.

Here, Rhodes found more undivided support than at the Phoenicia Diner, despite there being significantly fewer Democrats. He and the customers discussed issues affecting their everyday lives, such as health care and health infrastructure, storm recovery, vocational training and immigration.

Although his policy prescriptions might spring from big government liberalism, his framing carefully avoids political hot buttons. Storms such as Hurricane Irene frequently devastate these communities, causing flooding that resulted in fatalities and hundreds of millions of dollars in damages to New York alone, including the near destruction of one unlucky Catskills town. Rhodes did not mention, as would most New York City Democrats reflexively would, that more frequent and severe storms are a consequence of climate change. But he had the kind of bit-by-bit preparedness and infrastructure proposals that these women wanted to hear. “This young man is very refreshing. He spoke to our concerns, our needs. He’s a very good listener,” offered one of the women. “He’s very genuine,” another proclaimed.

“I’ll probably vote for him,” said a third woman, who explained that she looked into the other Democratic candidates, and that she is “glad to see him here, listening to what the local populace is interested in.” The rest nodded their heads. When the incumbent, Faso, was mentioned, the woman said, “I get a email from him once a week, and I’m very unhappy.” Another explained, “I was willing to give him a chance, but I’ve been very disappointed and no longer support him.” All the women said they planned to vote Democratic in the general election, but that most of them cannot vote for Rhodes in the upcoming primary because they’re registered as Republican or independent. Still, they’re no fans of Trump. “Let’s just move on,” said one, when asked how she felt about the president, “you’re talking to women here.”

Rhodes still had yet to enter true Trumpland. Then he went to Stamford, a town of 2,000 filled with decaying Victorian homes and daunting mountain peaks. It’s the kind of town where Trump could likely find some of his most dedicated supporters in New York state. With a populace that is overwhelmingly rural, white and not college educated, it would not seem to be fertile ground for a Democratic candidate.

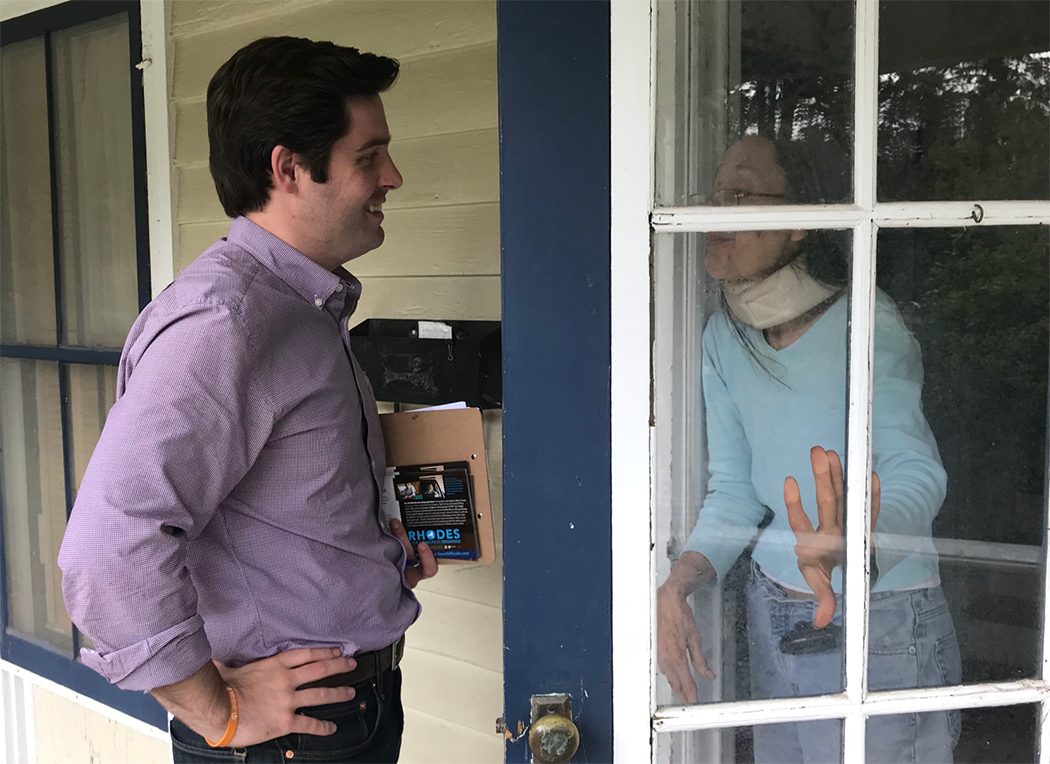

True to his mission, Rhodes went door-to-door. At one home, a one-story house resembling a very large shipping crate with windows, he came upon Charles and Mariellen Myers playing outside with their young son. These two, like most of their neighbors, were Trump supporters. “You’re running for Congress?” said Mariellen, a short woman with long grayish blond hair with a voice and demeanor similar to the most famous fictional Trump supporter, Roseanne Conner.

“Gosh, you’re still wet behind the ears,” she exclaimed. “Did you graduate high school yet?” asked the husband, a tough-looking gray-haired man with a protruding beer gut, who also pointed to a glaring example of Rhodes being an out-of-towner; “You really should be packin’, nobody’s packin’!” When asked what issues concerned them most, they said, practically in unison, “unions.” Charles Myers, a proud member of the carpenters union, felt increasingly concerned by the growing power of moneyed interests. “I’m the only candidate in the race endorsed by organized labor,” said Rhodes. Charles – apparently confused about which party is more union-friendly – looked up from Rhodes’ campaign literature and cautioned his wife, “He’s a Democrat.” They were skeptical.

Then Rhodes started talking about policy. The two love Trump – “I just wish the media would get out of his way,” they both declared – yet they were swayed by Rhodes’ progressive policy prescriptions. When he mentioned the the GOP’s tax cut passed in January, Mariellen expressed doubts about it. “Right, where did that come from?” she asked. Her husband, referring to the law’s heavy tilt in favor of the wealthy and corporations, lamented, “The little guy’s going to get screwed.”

Rhodes also made headway when talking about health care. When he mentioned, “We have a for-profit based health care system,” Mariellen interjected, “Right, right I said that to my mother-in-law literally yesterday.” She then detailed her mother-in-law’s health care woes: “She had an injection for an injury in her back, and the copay on it was $220, but yet every month that’s what she pays for her coverage.” After 20 minutes of agreeing on policy, these two Trump supporters agreed to do what seemed impossible: support a progressive Democrat. But only Charles is a registered Democrat and able to vote in the primary.

“The smaller the town, the more excited people are when you show up,” Rhodes said later, pointing out that the wife told him that she had “never seen someone on the federal level in this town.”

“The fundamental problem with politics in America today is that voters like that are completely ignored,” Rhodes added. But Rhodes won’t ignore these voters. He laid out his detailed plan for ensuring their support: sending follow-up emails, letters, handwritten notes and personal phone calls to all the voters he’d met that day – Democrat, Republican and independent.

The belief undergirding Rhodes’ campaign is now is the perfect time for Democrats to carve out a winning electoral coalition running through towns like Bovina and Stamford. “Right now is our opportunity,” he declared, referring to millennials like himself. “People are looking for something new. We have this opportunity now and it’s a chance for us to make the argument that we’re the generation that is inheriting a mess and we’re the generation that can fix it.” He then uttered a phrase that could very well become the next great rallying cry – on par with “Make America Great Again” – for millions of Americans: “We can give people hope again.”

NEXT STORY: More Tinder pickup lines for Suraj Patel