The news floated over New York’s solar industry like a dark cloud: The state was losing solar jobs.

A Feb. 7 report from the advocacy group The Solar Foundation found more than 100 jobs in New York’s solar energy industry were lost in 2016 from the year before. As one of only six states that lost positions last year – while the industry nationwide enjoyed a nearly 25 percent growth in jobs – the critiques came in quick. The Buffalo News shared the bad news, and a New York Post editorial wondered if Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s big investments in solar energy were going to waste. Both quoted Solar Foundation head Andrea Luecke, who blamed the job losses on regulatory delays killing off community solar projects.

Within two weeks, Cuomo’s office had a response: Solar is booming! The governor’s office sent out a press release touting an 800 percent growth in state-supported solar power over the past five years. New York had slightly more than 9,000 solar energy projects installed at the end of 2011. By the end of 2016, that figure had grown to 65,000 projects.

RELATED: Who were the big winners in the state budget agreement?

The growth was impressive, but a close analysis finds that even those numbers might not be enough to attain the high clean energy goals set by Cuomo’s office. And some industry experts say New York needs to make changes quickly if it wants to ride the solar wave.

“We’re sort of at this point where the rubber hits the road and we have to develop a pathway that is clear that sends very clear market signals to developers and financiers that these resources need to be developed,” said Jeff Cramer, executive director of the Coalition for Community Solar Access and a leading advocate for community solar, which recently became viable in New York thanks to new state regulations.

New York is in the midst of a promised clean energy revolution driven by the state’s Reforming the Energy Vision initiative. REV is a multipronged approach by state energy regulators to modernize the grid and make New York less reliant on fossil fuels. In fact, one of the main aspects of REV is mandating that 50 percent of the state’s electricity will come from renewable sources, like wind and solar, by 2030. Among its goals is installing 3,000 megawatts of solar electric capacity by 2023 with the help of public funds.

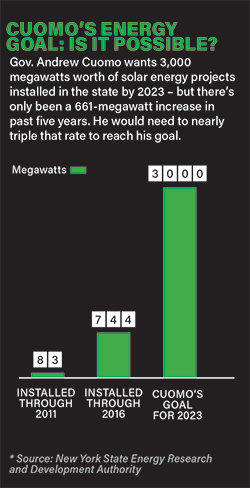

Reaching that 3,000-megawatt goal is a game of numbers. As of Dec. 31, 2016, the state had 744 megawatts of solar – by estimates from the governor’s office, that’s enough to power 121,000 average homes, or roughly all of Albany County. But it took the state five years to get from 83 megawatts of solar power in 2011 to the current 744 megawatts – so the state will need to nearly triple the rate of production over the next seven years to get to 3,000 megawatts. In his 2017 State of the State report, Cuomo touted 325 megawatts of community solar already in the pipeline and slated for financial support from the state.

“There’s a lot of ground to make up here to get to that goal,” said Rick Umoff, regulatory counsel and director of state affairs at the Solar Energy Industries Association, a national solar trade group. Umoff gives New York credit for its “pretty aggressive and impressive commitments for both solar and clean energy,” but says the state can do more to open up regulations and create more programs to encourage solar.

“If the amount of solar that is being discussed were actually happening, we could probably supply power to the entire northeast region.” – Jeff Cramer, executive director of the Coalition for Community Solar Access

Cramer agrees. “If we look at the past couple of years as an indicator of development only, we will not reach those goals.” And he thinks encouraging community solar is the answer. Community solar is a hybrid somewhere between solar panels on the roof of a house and a solar power plant, where many individuals or companies subscribe to use the power from a single installation at a centralized location. While many New Yorkers, especially in the city, can’t use traditional roof solar because they rent or their roof doesn’t fit the specifications, anybody can subscribe to community solar. That’s a plus for the Cuomo administration, which is concerned with expanding renewable energy access to low-income New Yorkers but has lacked ways to do that. Cramer says community solar is essential to reaching the state’s 3,000-megawatt goal, but the state regulations to make it viable only just came out in March, almost two years after he started talking with the state Public Service Commission.

Those regulations determined how the state will value the energy added to the electrical grid by community solar in a complex system called value of distributed energy resources, or VDER. New York previously used a system called net energy metering, which solar backers said didn’t accurately value their contributions to the grid. While standard rooftop solar installations will stay under net metering for now, the state introduced a stopgap measure on March 9 known as VDER Phase One that can get community solar installations up and running while state energy regulators and stakeholders work together to develop a more fair tariff. The community solar upstarts face some opposition from the major, powerful utilities like Con Edison and Central Hudson Gas & Electric that are wary of the costs of integrating community solar into the grid. The new Phase Two tariff may not be decided until the end of 2018.

Cramer says finalizing Phase Two would finally bring some predictability and hard numbers to community solar, but regulators will seemingly have to balance good policy that encourages development with a timeline that doesn’t kill all enthusiasm for the burgeoning industry. After all, it was this regulatory process that The Solar Foundation’s report blamed for job losses. The state Department of Public Service, which oversees the Public Service Commission, declined to comment for this story, but pointed to the Phase One order showing that community solar is not being held up.

David Sanbank, director of NY-Sun, the state office that promotes solar in New York, defended the state’s progress. “With the look of our pipeline and the way the residential market’s moving, we’re looking pretty solid here” to reach the 3,000-megawatt goal.

There’s certainly been no lack of interest from developers. More than 2,000 solar projects were proposed last year between April and December, most of which were community solar, leading to a huge backlog. The Journal-News reported in February that some towns in the Hudson Valley are putting a moratorium on leasing farmland out to solar developers, fearing the loss of too much productive farmland to unsightly panels. The solar frenzy had developers submitting plans for panels on sites they didn’t have the rights to yet, and some plots had two or more developers applying to build in the same place.

The state Public Service Commission stepped in to sheriff the Wild West of community solar, setting up guidelines for developers to meet to stay in the queue like showing consent of the landowner, completing an initial review of the electrical grid and putting some money down. But if that booming interest sounds like the answer to the state’s solar energy prayers, even Cramer of Coalition for Community Solar Access urges caution.

RELATED: Schneiderman promotes clean energy campaign in Buffalo

“If the amount of solar that is being discussed were actually happening, we could probably supply power to the entire Northeast region,” Cramer said. He added there’s already been a huge rate of attrition for developers who have signaled interest in the community solar market but won’t actually put money down and develop projects.

“The reality is that it’s going to be a far slower, more deliberate process,” he said. “The reality is, it’s going to take decades of time to fulfill even a percentage of the development that has been proposed or rumored upstate.”

That may be comforting to some Hudson Valley farmers, but not so much to Cuomo, who has just six years to reach the 3,000-megawatt goal.

One group with a big idea of how to reach that goal – with or without community solar – is the New York Public Interest Research Group, which has been leading a campaign against the state’s nuclear bailout. Starting this month, a small percentage of New York ratepayers’ electricity bills will be going to support three upstate privately run nuclear power plants. Cuomo says it’s crucial to keep the plants open as huge sources of energy for the state that don’t depend on fossil fuels, but Russ Haven, general counsel for NYPIRG, disagrees.

“We could be so far ahead (on clean energy goals) if we put the money going into propping up these failing nuclear plants into really cost-effective future-leaning opportunities (like solar),” he said.

Haven pointed to a study co-authored by Stanford University professor Mark Jacobson that found replacing the nuclear plants immediately with large-scale wind and solar could save New York $5.2 billion.

It’s an ambitious idea, and unlikely to happen, but it’s also a reminder that solar has a long way to go to dethroning nuclear power in the state. Solar currently makes up less than 2 percent of generating power in the state, and solar is significantly smaller in New York than other renewable resources like hydropower and wind. Those two sources alone make up more than 7,000 megawatts of power in the state, with much more proposed for the coming years.

Still, New York is going all-in on solar, with a recent directive from the governor’s office calling solar growth critical to meeting the state’s ambitious renewable energy goals. And for that, Cramer says New York needs to help out a little more.

“We have these lofty goals. The technology is definitely there to achieve those goals,” he said. “It’s ensuring that there’s a clear pathway towards achieving those goals.”