The heated national debate about whether families should get public money to send their kids to private schools is full of big questions.

Do vouchers raise test scores or lower them? Do they help or hurt students over the long term? Do they damage public schools or push them to improve?

Chalkbeat combed through some of the most rigorous academic studies to get the answers.

Two caveats before we begin: First, context matters. Researchers look at specific programs at certain times with their own sets of rules. New initiatives — like a dramatic expansion of private school choice programs of the sort the Trump administration has promised — could mean entering uncharted waters, where past research becomes a less reliable guide.

Second, the voucher debate is often based on values. Research studies can’t answer philosophical questions on whether public money should go to religious schools or if providing more choices for parents is an inherent good.

RELATED: De Blasio strikes deal with charter schools

With that in mind, here’s what you should know:

Recent studies suggest that vouchers lower student test scores in the short-run. But students who stay in private schools sometimes improve over time.

In the last couple of years, a spate of studies have shown that voucher programs in Indiana, Louisiana, Ohio, and Washington D.C. hurt student achievement — often causing moderate to large declines.

In Louisiana, after two years in the program, a student who started at 53rd percentile of performance had dropped to the 37th percentile in math. In D.C., students using a voucher fell seven percentile points in math and five points in reading after one year, compared to students who applied for a voucher but didn’t get one.

Advocates have pushed back, saying the programs were new and should be given more time to prove they work. Studies out of Indiana and Louisiana give some credence to that view.

In Indiana, students in the program saw initial dips in math achievement, but by year four those still in private school had caught up to their public-school peers. And in English, voucher students actually seemed to make gains after four years. These results, though, only applied to those who stayed in the program for four consecutive years.

In Louisiana, students in the upper elementary school grades saw huge test score drops in years one and two. Students caught up by year three in math and reading, though they still appeared to lag behind in social studies. Younger elementary students saw consistently big test score drops in math and social studies, though for methodological reasons, the researchers were less confident in these results.

The Ohio study showed that even three years into the program, the negative impacts of using a private school voucher persisted.

Older studies tended to show neutral or modest positive effects of vouchers on academic performance, and until recently, few if any studies had shown that vouchers actually led to lower achievement among students who received them. It’s not clear what has changed, but one theory is that public schools have improved — or at least gotten better at raising test scores — in response to accountability measures like No Child Left Behind.

Students sewing during a class at the School for Community Learning, a progressive Indianapolis private school that depends on vouchers. (Dylan Peers McCoy)

A handful of older studies show that vouchers have a positive or neutral impact on student outcomes later in life, like attending college or graduating high school.

Some supporters of vouchers downplay the recent studies by pointing to research on the longer-run effects of the programs. Here the studies are more positive, but they’re also limited and fairly old. In each case, the researchers looked at students who entered voucher programs at least a decade ago — a necessary trade-off when looking at long-term outcomes.

A study of Milwaukee’s long-running voucher program found that participants were more likely to graduate high school and attend four-year colleges. A 2010 federal analysis of the D.C. voucher program found that its students were 21 percentage points more likely to complete high school (according to a survey of their parents, not a direct measure of graduation). A private school scholarship program in New York did not lead to improvements in college enrollment on average, but did seem to have a positive effect for black and Hispanic students specifically.

It remains an open question whether the more recent initiatives can expect those results. The three older programs weren’t hurting test scores in the short term; all had positive or no effects on scores.

RELATED: State reaches deal on mayoral control, gives de Blasio extension

Vouchers or tax credit programs lead to test score gains in public schools.

There is a large body of evidence suggesting that public schools improve in response to competition from school voucher or tax credit programs, at least as measured by test scores.

This has been seen in studies of Florida, Louisiana, Milwaukee, Ohio, San Antonio, and even Canada. As a recent research overview put it, “Evidence on both small-scale and large-scale programs suggests that competition induced by vouchers leads public schools to improve.”

The impact, though, is often fairly small and can dissipate over time. There do not appear to be any studies on the effect of voucher competition on measures other than test scores.

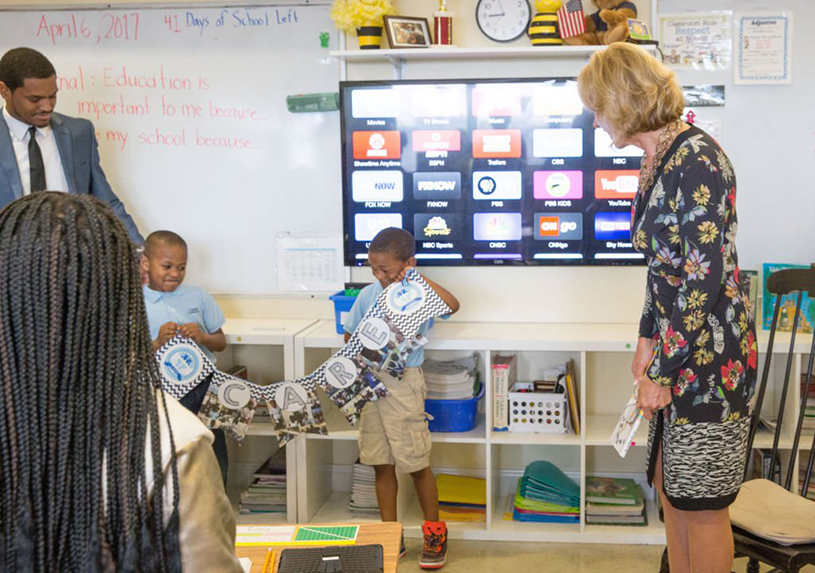

Attending a private school may improve parent satisfaction, particularly when it comes to school safety. (U.S. Department of Education)

Attending a private school may improve parent satisfaction, particularly when it comes to school safety.

Families tend to be more satisfied with private schools, though it’s not clear why.

The older D.C. study showed that families who received vouchers had higher rates of parent (but not student) satisfaction. The latest D.C. analysis showed parents perceived private schools as safer and seemed more satisfied with them overall, though the results weren’t statistically significant.

An older report by the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think tank, found that families of students with disabilities using a voucher in Florida were dramatically more satisfied with the new private school than their previous public school. A recent analysis of national data showed that private-school parents were also more satisfied than those sending their children to public schools — though it could not establish cause and effect.

We know almost nothing about how tax credit tuition programs affect participating students.

Despite their expansion in recent years, tax credit programs — which use generous tax breaks to incentivize donations to organizations that then offer private school scholarships — have rarely been studied.

These programs are similar to school vouchers, in that they redirect taxpayer dollars to private schools, but they tend to be significantly less regulated. For instance, they usually do not require participating private schools to take state tests or, in some cases, any standardized tests at all. That’s part of why there’s so little research on how using one of those scholarships affects students.

The only program that has been rigorously studied, Florida’s tax credit scholarship — the largest in the country — had either no effect or small positive effects on student test scores. But that was only prior to 2010; since then, changes to testing requirements have made direct comparisons to public school students impossible.

This story was originally posted on Chalkbeat, a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.