As Albany lawmakers clash over the future of mayoral control of city schools — and with the mayoral primary just months away — Chalkbeat has taken a close look at Mayor Bill de Blasio’s track record on education. What did he set out to do? Who benefits? And what does it mean for the city’s 1.1 million students?

As you’ll see in our week-long series, “An Education U-Turn,” New York City’s progressive mayor started with two different goals: He wanted to undo some of his predecessor Michael Bloomberg’s most radical reforms — moving away from closing long-struggling schools, for example. But he also wanted to set his own education agenda.

Our project dissects three different pieces of that plan: We looked in depth at the school system’s organization, struggling schools left out of the city’s main improvement programs, and the state of teacher training under Fariña, who is passionate about it.

But those topics represent only a small piece of the mayor’s approach to governing the country’s largest school district. Here’s a look at his promises on education — many of which date back to the campaign trail — and where they stand today.

RELATED: If mayoral control lapses, what's next for NYC schools?

New or expanded initiatives

Universal pre-kindergarten

On the campaign trail: De Blasio called for “truly universal pre-kindergarten for 4-year-olds.”

Mission accomplished. While Governor Andrew Cuomo blocked his plan to fund pre-K through a tax on wealthy households, the state did kick in $300 million for the plan. After a quick ramp up, de Blasio has created nearly 70,000 seats. While the program is far from perfect — it’s been criticized for being racially segregated, for instance — it is widely hailed as a success. In a recent poll, New York City voters ranked pre-K as the mayor’s top achievement.

In April, the mayor announced plans to extend the program to 3-year-olds, though it was not immediately clear whether he would be able to raise enough money to do so. The plan would also transfer oversight of roughly 20,000 children ages 0-3 from the Administration for Children’s Services to the Department of Education.

Creating more community schools

July 2014: “Community schools are to me … one of the thrusts that will have potentially the biggest impact.” Specifically, he committed to creating 100 community schools that could offer medical and social services, art and fitness programs, tutoring and more to students and their families.

Did it — and then some. The city has announced three rounds of community school expansions. First, it turned 40 schools into community hubs in June 2014 with $52 million in state funding. De Blasio said at the time that the schools’ success would be measured by improvements in student health, attendance and parent engagement as opposed to solely test scores.

Then the city brought the model to 94 of the city’s lowest-performing schools, dubbed “Renewal Schools.” In May 2017, the mayor announced another expansion, to 69 additional schools, bringing the total to 215. President Donald Trump’s budget raised questions about whether the city could afford the expansion.

Access to opportunity

On the campaign trail: “Let’s be honest about where we are today,” the mayor said during his campaign kickoff. “This is a place that in too many ways has become a tale of two cities, a place where City Hall has too often catered to the interests of the elite rather than the needs of everyday New Yorkers.”

Equity and Excellence: To improve the quality of all schools, the administration has launched several initiatives under the umbrella of “Equity and Excellence.” (Former Chancellor Joel Klein also used the phrase to describe his very different approach to the city’s schools.) The mayor has been criticized for the long timeline on these initiatives, some of which won’t be fully realized until 2026.

Here are some of the key components:

Universal Literacy

Goal: All students will read on grade level by the end of second grade.

Progress: The city hired 103 reading coaches during spring 2016. They were sent to districts in the Bronx and Brooklyn chosen because they had the largest share of third-grade students earning a level 1 of 4 on the state English exams.

Algebra for All

Goal: All students will complete algebra no later than ninth grade. By 2022, all students will have access to an algebra course in eighth grade, and to academic supports in elementary and middle school.

Progress: More than 400 teachers from fifth to 10th grade were offered special training in math instruction. Now, 67 elementary schools have “departmentalized” math to ensure that at least one teacher per school has special math training.

AP for All

Goal: 75 percent of students will be offered at least five AP classes by fall 2018. By fall 2021, students at all high schools will have access to at least five AP classes.

Progress: In 2016-17, new AP courses were added at 63 schools, including 31 that did not offer any last year. AP for All teachers get special training, including at a summer institute. Thousands more students are taking AP exams, though the upward trend predates de Blasio.

Mayor Bill de Blasio learns about computer science from a student at the Laboratory School of Finance and Technology in the Bronx. (Monica Disare / Chalkbeat)

Computer Science For All

Goal: By 2025, all NYC public school students will receive computer science education in elementary, middle, and high school. Over the next 10 years, the DOE will train nearly 5,000 teachers in computer science.

Progress: The city has trained 526 teachers across 298 schools participating in the program this year, putting the teacher-training rate on track to meet the goal. The program isn’t without its critics, though, some of whom argue that training non-specialists to teach computer science isn’t the best approach.

College Access For All

Goal: All middle school students will have the opportunity to visit a college campus and that every high school senior will graduate with a “college and career plan.”

Progress: The city announced in June that the program would expand to 193 middle schools next year, in addition to the 171 schools already participating. Meanwhile, 100 high schools were trained and received funding to improve college awareness. The city also started offering SATs during the school day and provides a fee waiver for CUNY applicants.

Single Shepherd

Goal: Every student in grades 6-12 in Districts 7 and 23 will have an assigned guidance counselor or social worker to help them in and out of school.

Progress: In 2016-17, the city hired 140 shepherds to serve 16,000 students across 51 schools. Your job will be “whatever it takes,” Fariña told them at an early training. While the ratio of 100 students per shepherd has raised eyebrows, it’s still lower than the recommended guidelines for social workers, which allow 250 students per adult. And some schools say having extra hands on deck makes a big difference.

District-charter partnerships

Goal: Allow district and charter schools to collaborate and share best practices.

Progress: 108 district and charter schools have partnered, including schools co-located in the same building, a district-wide program in Brooklyn’s District 16, and a partnership with Uncommon Schools. An additional 28 schools will be chosen to participate this coming fall.

Students participate in after-school activities at the community school at P.S. 61 Francisco Oller in the Bronx. (The Children's Aid Society)

Creating new after-school programs

On the campaign trail: De Blasio promised to “dramatically expand after-school programs for all middle schools students.”

Major increase. Prior to the expansion, the Department of Youth and Community Development and the DOE combined served an estimated 56,369 middle schoolers in 239 schools and community centers. In the first year of the middle school expansion (2014-15), that number nearly doubled to 111,448. This year, the city is slated to serve 116,000 middle school students.

Improving special education services

On the campaign trail: Pointing to low graduation rates for students with special needs, de Blasio promised “real reforms that provide the educational preparation for college and careers upon graduation.” He also pledged to improve the computer system for tracking their information, known as SESIS, and to improve bus service.

Fewer battles. After the administration curbed legal challenges against parents who want the city to pay for their children with disabilities to attend private schools, and the number of students getting tuition reimbursed between 2011 and 2015 rose 42 percent. The city also paid families without a legal fight 50 percent more often.

Uneven delivery. A recent study on special education services provided by the Department of Education found that in 2015-16, many students had long wait-times for services or got only some of the services they were mandated to receive. In November 2016, the city announced plans to improve SESIS, which was first launched under Mayor Bloomberg. The plan, though far from comprehensive, included a dozen new full-time positions for staffers and $6.3 million over five years for software upgrades and additional maintenance.

Improving English language learner services

On the campaign trail: De Blasio noted “there has been no school system-wide program to bring their achievement up to the level of other students. There are some effective programs that can serve as a model for a citywide effort.”

More programs. In April 2016, Fariña announced the opening of 38 new dual language and transitional bilingual education programs. Another 68 programs are set to open in September, including for the first time, an Urdu program.

Nothing to show yet. While graduation rates for all students continued to climb this past year, English learners experienced a dramatic drop in both New York City and the state. The city was quick to defend itself, saying its graduation rate was flat if you consider the number of students who were classified as English learners the year they graduated along with those who learned the language well enough to test out.

Reducing class sizes

On the campaign trail: “As mayor I would want to be held accountable for reducing class size. If in four years we don’t decrease class size, we’re making a huge mistake.”

Still an issue. A 2016 report found that classrooms across the city grew more crowded over the last decade, especially for the youngest students. The city added 44,000 new seats in overcrowded areas through its 2016 budget.

Expanding career and technical education

June 2015: “A career in technical education is where the strands all meet. And I’m very, very proud that New York City is being used as a model here for this effort,” the mayor said.

Solid progress. With industry partners, the city is opening 40 new CTE programs aligned to labor market needs by 2019. It will have to contend with the state’s long and stringent approval process for CTE programs.

Diversifying specialized high schools

April 2014: “We cannot have a dynamic where some of our greatest educational options are only available to people from certain backgrounds,” the mayor said, endorsing a push to change admissions practices at some specialized schools.

Scaled-back ambitions. Early in the mayor’s tenure, Fariña also expressed support for a bill in the state legislature that would require the five specialized schools under the city’s jurisdiction to consider multiple measures, including state test scores and attendance, and the city formed a task force of principals to consider new policies. The city’s newly released school diversity plan focuses on getting more students of color to score high on the exam. It promises to expand programs that have all been in place since 2016, to little effect so far.

Improving diversity overall

August 2016: “There’s some really great new models that look at economic diversity and other factors that allow us to do the work of diversifying schools,” the mayor said. “So to folks who say we want to see more, I understand where they are coming from and my simple answer is: You’re going to see more.”

Small steps. The mayor’s highly anticipated diversity plan, released in June, landed with a thud. Critics blasted the city’s refusal to use the word “segregation” in the plan and what some saw as its reliance on small-bore solutions. It does eliminate “limited unscreened” admissions in an effort to make access to those high schools more fair.

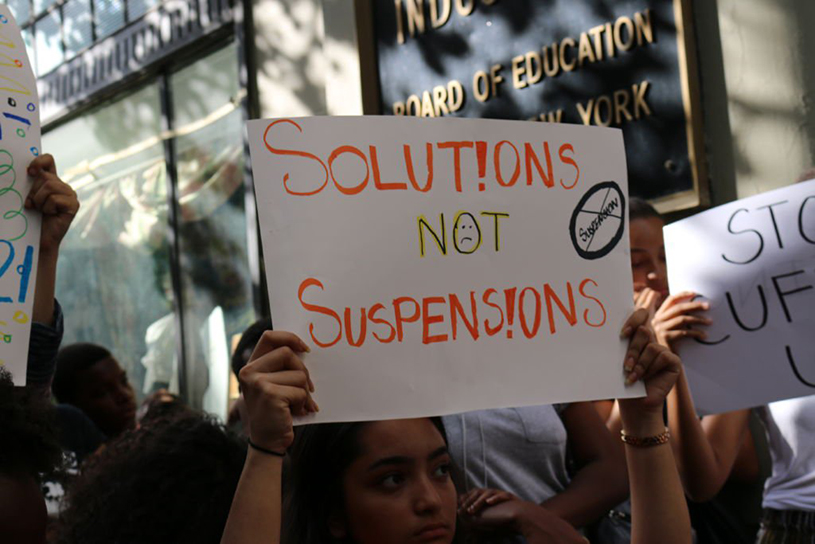

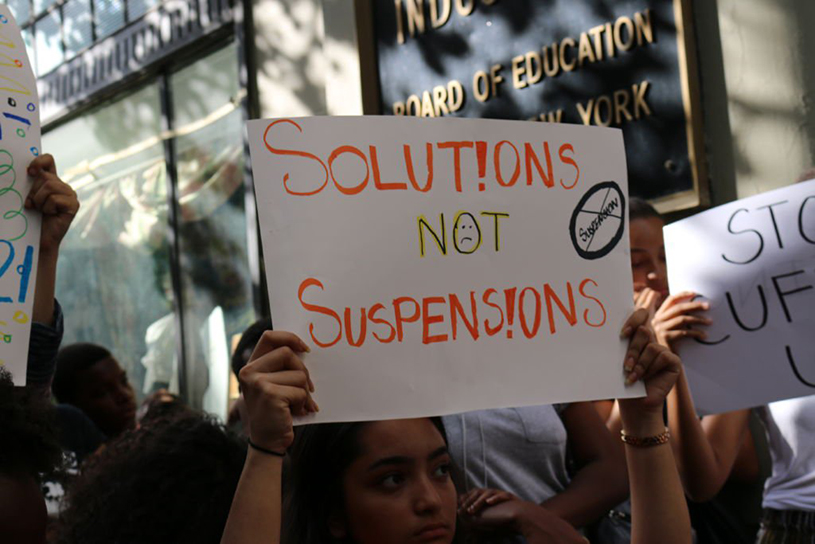

Advocates protest school suspension policy in August 2016. (Monica Disare / Chalkbeat)

Reducing suspensions

On the campaign trail: “There are too many suspensions. We’re not utilizing some of the tools we have to address problems.”

Significant progress. Suspensions have plummeted by 30 percent. And in 2015, the mayor announced plans to reduce punitive approaches to school discipline, expand the use of restorative justice, and develop metal detector protocols. In 2016, he followed that up by barring most suspensions for children in grades K-2 and letting principals request that metal detectors be added or removed from their schools.

RELATED: Will anyone back down in the face-off over mayoral control?

Accountability

Reducing the emphasis on standardized testing

On the campaign trail: “I would put the standardized testing machine in reverse. It is poisoning our system.” His platform included commitments to eliminate single-test admissions for gifted and talented programs and specialized high schools and to increase the use of portfolio assessments in schools.

On trend. As the state has scaled back testing and how scores can be used, the city has followed suit. But the city is still using test scores to decide who gets into gifted programs.

Changing how schools are graded

On the campaign trail: De Blasio said the letter grades should be done away with. “Educators, experts and parents will be convened to determine if the progress reports are the most effective long-term way to evaluate schools,” he said in 2013.

New approach. Department of Education officials eliminated letter grades, though schools still get summative progress reports.

Reducing school closures

On the campaign trail: “To too many people over at the Tweed building, closing a school is a panacea,” the mayor said. “They think it will solve all our problems.”

Big changes. Mayor de Blasio has largely avoided closing schools, except as a “last resort.” According to the city, 54 schools that began to phase out under the last administration were closed between 2014 and 2016. Under de Blasio, four schools were closed in 2016, and there were 12 consolidations involving 25 schools. An additional 6 schools are closing this year, with an additional 8 consolidations involving 16 schools.

Improving struggling schools

2014: “We will demand fast and intense improvement – and we will see that it happens.” That’s how the mayor described the “renewal schools” program, an effort to improve 94 struggling schools.

Not so fast. Though the mayor promised improvements within three years, we are nearing that deadline and the signs are mixed at best. Graduation rates at the city’s 31 Renewal high schools have increased 7 percent since 2014, more than the 4.2 percent average boost across all high schools over the same timeframe. But the schools also graduated far fewer students, and dropout rates went up at nearly half the schools.

Changing the support structure for schools

On the campaign trail: “Districts matter,” the mayor said. “We need to find a way to get parents to be able to talk to someone at the district level; teachers, parents relating to leadership at the district level again.”

Major shake-up. Fariña dramatically reorganized the city’s school system, re-empowering superintendents, reining in principals’ autonomy and eliminating networks in favor of more centralized borough field support offices. Principals say the result is more scrutiny over their daily decision-making.

Mayor Bill de Blasio held a press conference to demonstrate business leaders’ support for mayoral control in May 2016. (NYC Mayor's Office)

Leadership

Mayoral control

January 2016: “As you know, I believe fundamentally, as a matter of philosophy, that mayoral control should be made permanent. I don’t believe there is another system that works,” the mayor said.

No luck. De Blasio has sought multi-year extensions of mayoral control three years running, but has been granted only single-year extensions thus far.

Appointing Panel for Educational Policy members

On the campaign trail: De Blasio said the mayor should appoint the majority of members, but that they should serve fixed terms so that they have “freedom to actually speak their mind.”

Didn’t happen. De Blasio did appoint the majority of members, but they were not appointed to fixed terms. They rarely, if ever, vote against the city.

RELATED: The charters debate is more than Republicans vs. Democrats

Charter schools

Giving charter schools free space in public buildings

On the campaign trail: “There is no way in hell that Eva Moskowitz should get free rent, OK? There are charters that are much, much better endowed in terms of resources than the public sector ever hoped to be. It is insult to injury to give them free rent.”

That didn’t work out. Before de Blasio even had a chance to follow through on his pledge to charge rent to charter schools, the state legislature banned it and, in fact, required de Blasio to pay for the space of any new charter. And when de Blasio tried to kick out three Success Academy schools from public school space, he was sued and quickly found space for them in leased buildings. Charter schools continue to claim the city is sitting on valuable classroom space they could use.

Expanding the city’s charter sector

On the campaign trail: “We don’t need new charters.”

Growing sector. Since the mayor took office, the charter sector has continued to grow and now serves more than 100,000 city children. In an interview with Chalkbeat, Success Academy CEO Eva Moskowitz predicted that the state would lift its cap and the sector would double within four years.

Harsh words. While the mayor made some conciliatory gestures early on, his more recent rhetoric has been more critical, like when he took a dig at charters last summer for focusing too heavily on test prep and “excluding kids with behavior issues that have to be addressed or who don’t test well.”

RELATED: NYC principals adjust to a reined-in role under Carmen Fariña

Teachers and principals

Evaluating teachers and principals

On the campaign trail: “The new system is a tremendous improvement over the past,” de Blasio said. “I remain concerned about the extent to which scores on state tests will factor into teacher evaluations and believe we need to watch closely how the pilot use of student surveys to rate teachers plays out in our schools.”

Significant rollback. The state’s policymaking body did most of the heavy lifting by placing a moratorium on the use of state 3-8 math and English tests in teacher evaluations. But the union also pushed for more “authentic assessments” in evaluating teachers and, in a 2016 deal, the city continued its shift away from using multiple-choice tests to judge them.

Attracting and retaining local teachers

On the campaign trail: “The city needs to encourage New Yorkers to consider teaching as a profession by expanding ‘grow your own’ programs in high schools, teacher residency programs, and partnerships with CUNY and SUNY colleges.” His platform called for the creation of new categories like “lead teachers” and “master teachers” to encourage retention.

Making progress. De Blasio followed through by creating teacher leadership positions, with higher pay and more responsibility, which were negotiated into the city’s 2014 contract with the United Federation of Teachers.

Politics aside, I will never be able to fathom the idea that disabled people are liabilities + taking health care away from millions is good. Let alone in the name of tax breaks for the very wealthy.

New hires. The administration hired 1,000 teachers each of the two years of the Pre-K for All expansion. Those teachers received professional development sessions, onsite coaching and access to other resources. The mayor also announced NYC Men Teach, an initiative to train or hire 1,000 male teachers of color by 2018. The city says 912 have been put on the path to certification or hired since November 2015, and it expects to reach its goal by fall 2018.

Correction: This story has been corrected to clarify that not all of the 912 male teachers of color have been hired.

This story originally ran on Chalkbeat, a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.