On a tree-lined road in the heart of Westchester County, it is easy to assume that Brookside Elementary School in Ossining is a stereotypical well-funded suburban school. Property taxes in the county are higher than anywhere else in the country, and the population is still increasing, just like it was in the 1960s when the fictional Sally Draper of “Mad Men” fame attended Brookside.

Things are very different now though, according to Ray Sanchez, superintendent of the Ossining Union Free School District. Rising enrollment meant the school library was split in two in order to create a new classroom. Students learning English as a second language study in a space behind a curtain as cafeteria workers prepare lunch on the other side. A combination of increasing enrollment, rising poverty and more special-needs students mean that the district needs more state funding to keep up, Sanchez said. “Those three things in my opinion should be driving dollars to help address the various needs that exist,” he said. The $85,000 funding increase in Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s proposed state budget is not enough for the district’s six schools, according to Sanchez, who has joined with other superintendents to form a group called the Harmed Suburban Five.

There are reasons for Sanchez and other educators to be optimistic about their funding prospects in the upcoming year. Democrats won big majorities in the state Senate and Assembly last year in part on a platform of increasing funding for public schools. Newly elected legislators include state Sen. Robert Jackson, who was the lead plaintiff in the landmark 2006 Campaign for Fiscal Equity ruling, and state Sen. Shelley Mayer, who represents a nearby Westchester County district, chairs the Education Committee. “The Assembly Democratic conference always fought tooth and nail to get more money for school funding,” Mayer said in December. “We just couldn’t always get all that was deserved. So I’m hopeful that this is a great moment to move forward on this very basic priority for every district. That’s the No. 1 issue.”

But with just a month until the April 1 state budget deadline, significant disagreements on school funding remain between Cuomo – with his proposed $27.7 billion education budget – and key Democratic lawmakers who want to push that number higher. At the heart of the dispute is the Campaign for Fiscal Equity ruling to provide a sound basic education for all students. Legislation enacted after the ruling – the State Education Budget and Reform Act – allocated $5.5 billion in funding for Foundation Aid, which was meant to help poorer school districts, but that funding dried up once the Great Recession hit in 2009. Lawmakers say the state owes more than $4 billion in retroactive Foundation Aid funding to school districts statewide and want $1.66 billion of it this year. Cuomo has disagreed – saying in December that the Foundation Aid program and CFE lawsuit were “ghosts of the past” – but proposed $338 million in additional funding nonetheless.

Teachers, school officials, activists and the state Board of Regents back the lawmakers, but Cuomo has substantial leverage over the budget process. Plus, an unexpected $2.3 billion budget shortfall makes money even tighter in Albany.

The lawmakers’ push for more education funding is also complicated by two other proposals in the executive budget. One would increase the state’s authority over how aid reaches individual schools, and another would consolidate a variety of aid programs – measures that some key lawmakers say need to be dropped before a budget deal can be reached.

“We are all talking about the same thing, education equity,” Mayer said in a recent interview. “This is the path to the middle class for these students, but they have to have the really strong basics (that) an appropriately funded school can provide.”

In practice, Cuomo and state lawmakers have very different ideas about what “equity” means. With the highest per-pupil spending in the nation, Cuomo has argued for months that more needs to be done to ensure that districts allocate increases in education funding to the schools that need it most. Beginning with the 2017-2018 school year, New York City schools and 75 other school districts had to report how much they spent per student at each of their schools. A total of 306 districts will do the same this year, with all 674 districts that receive Foundation Aid reporting such data next year.

"It was a scam. You gave money to the poorer district, but they didn't give it to the poorer schools." - Gov. Andrew Cuomo

The data reported by the first 76 districts is at the heart of Cuomo’s argument that districts must be compelled to direct more to schools with relatively low per-pupil spending. A November report from the the Rockefeller Institute of Government found that the poorest schools in New York City get 12 percent less per student than the wealthiest schools. In Buffalo, the poorest schools received 26 percent less per student than the richest schools. Cuomo called the current school funding formula a “scam” in January. “You gave money to the poorer district, but they didn’t give it to the poorer schools,” he said.

The governor’s budget proposal would require districts to prepare “equity plans” – subject to the review and approval of the state Education Department – to detail how they will increase per-pupil spending at high-need schools, as defined by the state Division of the Budget. “The school district is responsible for coming up with a plan, and in doing so, they maintain local control,” said Morris Peters, a budget division spokesman. “Only if the school district fails in their responsibility to develop an approvable plan would (the state Education Department) intercede as a backstop, but the intent is for the local school district to tackle the important problem of school inequity with their own solution.”

Critics like Jackson insist that Cuomo’s proposal only moves the state further away from its original Foundation Aid targets. “The Governor’s plan to address the supposed ‘inequities’ within districts is a smoke-and-mirrors game intended to erase the Campaign for Fiscal Equity,” he said in a Feb. 4 statement. “But the Foundation Aid formula must be fulfilled.”

Critics say categorizing which schools count as wealthier than others is all relative. “The Buffalo schools that the Rockefeller report classifies as wealthy have student poverty rates as high as 77 percent,” the Alliance for Quality Education said in a press release. “The same pattern exists in other high need districts included in the report.”

Lawmakers, activists and educators are also skeptical of a proposal to consolidate several different funding programs into a single funding source. In past years, this funding was used to reimburse districts for expenses like new school buses, computers and textbooks. But Cuomo’s plan to cut costs by streamlining the process makes some lawmakers suspicious about how a wide range of expenses would have to compete against each other. “That’s just a naked attempt to reduce the overall amount of aid for these functional budgets,” said state Sen. John Liu, chairman of the New York City Education Committee.

At a Feb. 6 legislative budget hearing, lawmakers, school administrators and activists were largely opposed to Cuomo’s changes and the amount of education aid that he proposed. State Education Commissioner MaryEllen Elia noted in her testimony that she and the Board of Regents recommended $1.3 billion more in Foundation Aid than Cuomo, and multiple advocates and experts argued that judging equity by comparing per-pupil spending can be misleading. “School spending isn’t like water,” according to testimony from the New York State Council of School Superintendents. “One glass is a bit low, so pour a little more water in that one.” Jennifer Pyle, executive director of the Conference of Big 5 School Districts – which represents Buffalo, New York City, Rochester, Syracuse and Yonkers – said that school-level reporting requirements add another layer of administrative work while providing data of questionable value. New York City schools Chancellor Richard Carranza testified that school administrators have a complex decision-making process to figure out how new school funding should divvied up among 1,600 schools – rather than basing those decisions largely on per-pupil spending.

Democrats may now have strong majorities in the state Legislature, but the dynamics of this year’s education funding battle could boil down to the same bottom line as in years past. “It’s always a difficult time trying to find money for all the good things in government,” said Assemblyman Michael Benedetto, who chairs the Education Committee. “It is not just education, you’re also talking about health and transportation too. These are all important needs that our state must somehow fund. … Certainly though, the education of our children is paramount and that has to be one of the principal things we look at. That’s what we are going to be trying to do in the next few weeks and hopefully, by the end, we will find a way to satisfy all of those needs.”

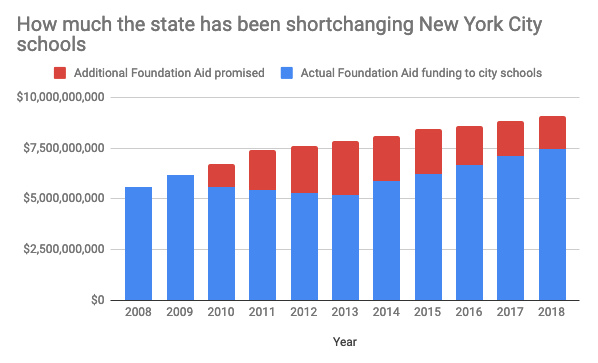

How much the state has been shortchanging New York City schools

In 2007, in the wake of the Campaign for Fiscal Equity ruling, New York agreed to increase its Foundation Aid funding to New York City schools. But the state has since fallen short of its own formula.

NEXT STORY: Can New York win another HQ2?